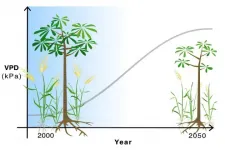

(Press-News.org) A global observation of an ongoing atmospheric drying -- known by scientists as a rise in vapor pressure deficit -- has been observed worldwide since the early 2000s. In recent years, this concerning phenomenon has been on the rise, and is predicted to amplify even more in the coming decades as climate change intensifies.

In a new paper published in the journal Global Change Biology, research from the University of Minnesota and Western University in Ontario, Canada, outlines global atmospheric drying significantly reduces productivity of both crops and non-crop plants, even under well-watered conditions. The new findings were established on a large-scale analysis covering 50 years of research and 112 plant species.

"When there is a high vapor pressure deficit, our atmosphere pulls water from other sources: animals, plants, etc.," said senior author Walid Sadok, an assistant professor in the Department of Agronomy and Plant Genetics at the University of Minnesota. "An increase in vapor pressure deficit places greater demand on the crop to use more water. In turn, this puts more pressure on farmers to ensure this demand for water is met -- either via precipitation or irrigation --so that yields do not decrease."

"We believe a climate change-driven increase in atmospheric drying will reduce plant productivity and crop yields -- both in Minnesota and globally," said Sadok.

In their analysis, researchers suspected plants would sense and respond to this phenomenon in unexpected ways, generating additional costs on productivity. Findings bear out that various plant species -- from wheat, corn, and even birch trees -- take cues from atmospheric drying and anticipate future drought events.

Through this process, plants reprogram themselves to become more conservative -- or in other words: grow smaller, shorter and more resistant to drought, even if the drought itself does not happen. Additionally, due to this conservative behavior, plants are less able to fix atmospheric CO2 to perform photosynthesis and produce seeds. The net result? Productivity decreases.

"As we race to increase production to feed a bigger population, this is a new hurdle that will need to be cleared," said Sadok. "Atmospheric drying could limit yields, even in regions where irrigation or soil moisture is not limiting, such as Minnesota."

On a positive note, the analysis indicates different species or varieties within species respond more or less strongly to this drying depending on their evolutionary and genetic make-up. For example, in wheat, some varieties are less responsive to this new stress compared to others, and this type of variability seems to exist within other non-crop species as well.

"This finding is particularly promising as it points to the possibility of breeding for genotypes with an ability to stay productive despite the increase in atmospheric drying," said Sadok.

Danielle Way, a plant physiologist and co-author of the study from Western University, sees similar outcomes when it comes to ecosystems.

"Variation in plants' sensitivity to atmospheric drying could also be leveraged to predict how natural ecosystems will respond to climate change and manage them in ways that increase their resilience to climate change," she said.

In the future, researchers believe these findings can be used to design new crop varieties and manage ecosystems in ways that make them more resilient to atmospheric drying. However, new collaborations are needed between plant physiologists, ecologists, agronomists, breeders and farmers to make sure the right kind of variety is released to farmers depending on their specific conditions.

"Ultimately, this investigation calls for more focused interdisciplinary research efforts to better understand, predict and mitigate the complex effects of atmospheric drying on ecosystems and food security," Sadok and Way said.

The research was funded by grants from the Minnesota Wheat Research & Promotion Council, the Minnesota Soybean Research and Promotion Council and the Minnesota Department of Agriculture.

INFORMATION:

Lockdown and other restrictions imposed to control the COVID-19 pandemic have had unseen negative effects on the cognitive capacity and mental health of the population. A study led by the UOC's research group Open Evidence, in collaboration with international universities and BDI Schlseinger Group Market Research, has gauged the impact of the measures taken during the first and second waves of the virus on citizens of three European Union countries. The study concludes that the shock produced by the situation has reduced people's cognitive capacity, leading them to take more risks, ...

Astronomers have discovered new hints of a giant, scorching-hot planet orbiting Vega, one of the brightest stars in the night sky.

The research, published this month in The Astrophysical Journal, was led by University of Colorado Boulder student Spencer Hurt, an undergraduate in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences.

It focuses on an iconic and relatively young star, Vega, which is part of the constellation Lyra and has a mass twice that of our own sun. This celestial body sits just 25 light-years, or about 150 trillion miles, from Earth--pretty close, astronomically speaking.

Scientists can also see Vega with telescopes even when it's light out, which makes ...

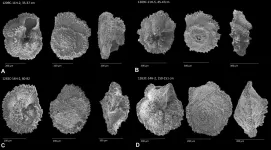

Microscopic fossilized shells are helping geologists reconstruct Earth's climate during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), a period of abrupt global warming and ocean acidification that occurred 56 million years ago. Clues from these ancient shells can help scientists better predict future warming and ocean acidification driven by human-caused carbon dioxide emissions.

Led by Northwestern University, the researchers analyzed shells from foraminifera, an ocean-dwelling unicellular organism with an external shell made of calcium carbonate. After analyzing the calcium isotope composition of the fossils, the researchers concluded that massive volcanic activity injected large amounts of carbon dioxide into the Earth system, causing global warming and ocean acidification.

They ...

Artificial intelligence can already scan images of the eye to assess patients for diabetic retinopathy, a leading cause of vision loss, and to find evidence of strokes on brain CT scans. But what does the future hold for this emerging technology? How will it change how doctors diagnose disease, and how will it improve the care patients receive?

A team of doctors led by UVA Health's James H. Harrison Jr., MD, PhD, has given us a glimpse of tomorrow in a new article on the current state and future use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the field of pathology. Harrison and other members of the College of American Pathologists' Machine Learning ...

In a new paper published in Light: Science & Applications, the group led by Professor Andrea Fratalocchi from Primalight Laboratory of the Computer, Electrical and Mathematical Sciences and Engineering (CEMSE) Division, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Saudi Arabia, introduced a new patented, scalable flat-optics technology manufactured with inexpensive semiconductors.

The KAUST-designed technology leverages on a previously unrecognized aspect of optical nanoresonators, which are demonstrated to possess a physical layer that is completely equivalent to a feed-forward deep neural network.

"What we have achieved," explains Fratalocchi, "is a technological process to cover ...

Women are largely being excluded from decisions about conservation and natural resources, with potentially detrimental effects on conservation efforts globally, according to research.

A University of Queensland and Nature Conservancy study reviewed a swathe of published conservation science, investigating the cause and impact of gender imbalance in the field.

UQ PhD candidate and Nature Conservancy Director of Conservation in Melanesia Robyn James said it was no secret that females were underrepresented in conservation science.

"In fact, according to a recent analysis of 1051 individual top?publishing authors in ecology, evolution and conservation research, only 11 per cent were women," Ms James said.

"We analysed more than 230 peer-reviewed articles attempting ...

One of the world's rarest tree species has been transformed into a sophisticated model that University of Queensland researchers say is the future of plant research.

"Macadamia jansenii is a critically endangered species of macadamia which was only described as a new species in 1991," said Robert Henry, Professor of Innovation at the Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation (QAAFI).

"It grows near Miriam Vale in Queensland and there are only around 100 known trees in existence."

However, with funding from Hort Innovation's Tree Genomics project, and UQ's Genome Innovation Hub Macadamia jansenii has now become the world's most sophisticated plant research model.

Professor Henry said ...

In a perfect world, what you see is what you get. If this were the case, the job of artificial intelligence systems would be refreshingly straightforward.

Take collision avoidance systems in self-driving cars. If visual input to on-board cameras could be trusted entirely, an AI system could directly map that input to an appropriate action -- steer right, steer left, or continue straight -- to avoid hitting a pedestrian that its cameras see in the road.

But what if there's a glitch in the cameras that slightly shifts an image by a few pixels? If the car blindly trusted so-called "adversarial inputs," it might take unnecessary and potentially dangerous action.

A new deep-learning algorithm developed by MIT researchers is designed to help machines ...

Cancers that are resistant to radiotherapy could be rendered susceptible through treatment with immunotherapy, a new study suggests.

Researchers believe that manipulating bowel cancers based on their 'immune landscape' could unlock new ways to treat resistant tumours.

Cancers can evolve resistance to radiotherapy just as they do with drugs.

The new study found that profiling the immune landscape of cancers before therapy could identify patients who are likely to respond to radiotherapy off the bat, and others who might benefit from priming of their tumour with immunotherapy.

Scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, in collaboration with the University of Leeds and The Francis Crick ...

The public doesn't need to know how Artificial Intelligence works to trust it. They just need to know that someone with the necessary skillset is examining AI and has the authority to mete out sanctions if it causes or is likely to cause harm.

Dr Bran Knowles, a senior lecturer in data science at Lancaster University, says: "I'm certain that the public are incapable of determining the trustworthiness of individual AIs... but we don't need them to do this. It's not their responsibility to keep AI honest."

Dr Knowles presents (March 8) a research paper 'The Sanction of Authority: Promoting Public Trust in AI' at the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency (ACM FAccT).

The ...