(Press-News.org) Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major cause of disability and a risk factor for early-onset dementia. The injury is characterized by a physical insult followed acutely by complement driven neuroinflammation. Complement, a part of the innate immune system that functions both in the brain and throughout the body, enhances the body's ability to fight pathogens, promote inflammation and clear damaged cells. Complement plays a role in the brain, regardless of infection or injury, as it influences brain development and synapse formation. In TBI, complement- induced inflammation partially determines the outcome in the weeks immediately following injury. However, more research is needed to define a role for the complement system in neurodegeneration following head injury, specifically in the long-term, chronic phase of TBI. Furthermore, therapeutic management of TBI patients is limited to the acute phase following injury, as little is known about the link between the initial insult and the chronic neurodegeneration and cognitive decline in the months and years that follow.

Researchers at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), the Ralph H. Johnson VA Medical Center and elsewhere have reported a link between the complement system and the chronic phase of TBI. Their results, published online on Jan. 12 in the Journal of Neuroscience, showed that inhibition of complement at two months after TBI disrupts neurodegeneration and improves cognitive function.

"TBI is associated with cognitive decline and dementia, and there are zero pharmacological treatments to prevent that cognitive decline," said Stephen Tomlinson, Ph.D., a professor and interim chairman of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, who studies brain injury and the complement system.

"The vast majority of studies that have been done investigating different therapeutics in TBI have all been done with acute treatments, within hours of the initial insult. Our study is significant because we are starting treatments out to two months after TBI."

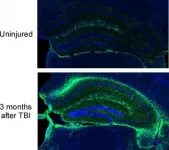

To understand more fully the timing of complement and chronic TBI, the Tomlinson Lab first looked at the body's response to the damaged area. They showed that certain brain cells, called microglia, destroy neuronal synapses that have been marked by complement for degradation. This process reduces the overall number and density of synapses in the brain. Further, they reported ongoing complement activation up to three months after one initial TBI insult, with expanding neuroinflammation across brain regions. This inflammatory response promotes degeneration of synapses and was predictive of progressive cognitive decline.

The researchers then explored the therapeutic effects of blocking complement. They used a complement inhibitor that specifically targets sites of complement activation and brain cell injury. Inhibiting complement interrupted the decline in brain cell function and reversed mental losses on tasks that evaluate spatial learning and memory, even when delivery of the inhibitor was delayed until two months after the injury.

"One big advantage of our approach is that we do not systemically inhibit complement," said Tomlinson.

"With acute treatments, it is not that big of an issue but chronically treating someone with a complement inhibitor systemically is not optimal because complement does other important things, ranging from host defense to controlling homeostatic and regenerative mechanisms."

Thus far, therapeutic investigations in preclinical models have focused almost entirely on acute treatments for TBI. With this new insight into TBI pathology, the Tomlinson team suggests that all phases of injury, including chronic time points, may be responsive to therapeutic treatments, specifically those involving complement inhibition.

These findings are critical, as rehabilitative interventions are the only available management strategy for TBI to improve cognitive and motor functions. Additionally, cumulative evidence shows that rehabilitation is likely to speed up recovery but not change long-term outcomes.

"It gives us a new way of perceiving TBI management. Really, the only therapy at the moment is rehabilitation therapy, which clinically has very little benefit. We have found that rehabilitation and complement inhibition have additive effects," said Tomlinson.

Looking forward, Tomlinson wants to take the translational approach of complement inhibition in the chronic phase of TBI out further, past that two-month window, and is investigating whether the treatment will still work in mice if it is begun six months to a year out from the initial TBI. Additionally, Tomlinson is developing models of repetitive TBI and plans to investigate anxiety and depressive behaviors in addition to early onset dementia, a significant concern in regard to veterans, soldiers and athletes.

Currently, multiple complement inhibitors are in various stages of clinical development, including those that are targeted specifically to sites of injury and disease. Tomlinson himself is a co-founder of a company that is investigating targeted complement inhibition, leading to the potential of incorporating complement inhibition into the clinic. Thus, studies undertaken in the Tomlinson lab could have deep and lasting impacts at the clinical level, where complement inhibition could eventually help the thousands of patients that suffer from TBI each year.

INFORMATION:

About MUSC

Founded in 1824 in Charleston, MUSC is the oldest medical school in the South, as well as the state's only integrated, academic health sciences center with a unique charge to serve the state through education, research and patient care. Each year, MUSC educates and trains more than 3,000 students and 700 residents in six colleges: Dental Medicine, Graduate Studies, Health Professions, Medicine, Nursing and Pharmacy. The state's leader in obtaining biomedical research funds, in fiscal year 2018, MUSC set a new high, bringing in more than $276.5 million. For information on academic programs, visit http://musc.edu.

As the clinical health system of the Medical University of South Carolina, MUSC Health is dedicated to delivering the highest quality patient care available while training generations of competent, compassionate health care providers to serve the people of South Carolina and beyond. Comprising some 1,600 beds, more than 100 outreach sites, the MUSC College of Medicine, the physicians' practice plan and nearly 275 telehealth locations, MUSC Health owns and operates eight hospitals situated in Charleston, Chester, Florence, Lancaster and Marion counties. In 2019, for the fifth consecutive year, U.S. News & World Report named MUSC Health the No. 1 hospital in South Carolina. To learn more about clinical patient services, visit http://muschealth.org.

For cancer cells to metastasize, they must first break free of a tumor's own defenses. Most tumors are sheathed in a protective "basement" membrane -- a thin, pliable film that holds cancer cells in place as they grow and divide. Before spreading to other parts of the body, the cells must breach the basement membrane, a material that itself has been tricky for scientists to characterize.

Now MIT engineers have probed the basement membrane of breast cancer tumors and found that the seemingly delicate coating is as tough as plastic wrap, yet surprisingly elastic like a party balloon, able to inflate to twice its original size.

But while a balloon becomes much easier to blow up after some initial effort, the team found that a basement membrane becomes stiffer as it expands. ...

Found around the world, powdery mildew is a fungal disease especially harmful to plants within the sunflower family. Like most invasive pathogens, powdery mildew is understudied and learning how it affects hosts can help growers make more informed decisions and protect their crops.

Scientists at the University of Washington and the University of Central Florida inoculated 126 species of plants in the sunflower family with powdery mildew, growing 500 plants from seeds that were collected from the wild and provided from the USDA germplasm network. Through this ...

BOSTON - The higher rates of obesity in Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) compared with other groups in the United States can be attributed in large part to systemic racism, according to a new perspective article published in the Journal of Internal Medicine. The authors offer a 10-point strategy to study and solve the public health issues responsible for this disparity.

"First, it is important to recognize that the interplay of obesity and racism is real. Once persons recognize this, they can begin to appropriately address and treat obesity in BIPOC communities," says co-author Fatima Cody ...

Women who experienced hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDPs) but did not develop chronic hypertension have a greater risk of premature mortality, specifically cardiovascular disease (CVD)-related deaths, according to a study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC). A separate JACC study examined the cardiovascular health risks associated with pregnancy in obese women with heart disease.

HDPs, which occur in approximately 10% of all pregnancies worldwide, are among the most common health issues during pregnancy. There are four types of HDPs: chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension (GHTN), preeclampsia and ...

Other senses re-routed during evolution, but not sense of smell

Loss of smell linked to depression and poor quality of life

Smell research can help treatments for loss in COVID-19

CHICAGO ---Odors evoke powerful memories, an experience enshrined in literature by Marcel Proust and his beloved madeleine.

A new Northwestern Medicine paper is the first to identify a neural basis for how the brain enables odors to so powerfully elicit those memories. The paper shows unique connectivity between the hippocampus--the seat of memory in the brain--and olfactory areas in humans.

This new research suggests a neurobiological basis for privileged access by olfaction to memory areas in the brain. The study compares connections between primary sensory areas--including ...

Researchers have developed a spectroscopic microscope to enable optical measurements of molecular conformations and orientations in biological samples. The novel measurement technique allows researchers to image biological samples at the microscopic level more quickly and accurately.

The new instrument is based on the discrete frequency infrared spectroscopic imaging technique developed by researchers at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

"This project is about bringing the study ...

DALLAS - March 8, 2021 - A study led by UT Southwestern and Children's Health researchers defines parameters for the number of white blood cells that must be present in children's urine at different concentrations to suggest a urinary tract infection (UTI). The findings, published recently in Pediatrics, could help speed treatment of this common condition and prevent potentially lifelong complications.

UTIs account for up to 7 percent of fevers in children up to 24 months old and are a common driver of hospital emergency room visits. However, says study leader Shahid Nadeem, M.D., assistant professor of pediatrics at UTSW as well as an emergency department physician and pediatric nephrologist at Children's Medical Center Dallas, these bacterial infections ...

Boston, MA - Financial pollution arises when exorbitant or unnecessary healthcare spending depletes resources needed for the wellbeing of the population. This is the subject of a JAMA Health Forum Insight co-authored by researchers in the Department of Population Medicine at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School. The Insight was published in the March 8, 2021 issue of JAMA Health Forum.

The authors lay out the rationale for "financial pollution" as a metaphor to express the urgency of addressing wasteful health care spending and to guide innovative policymaking. Akin to environmental pollution, financial ...

When a coastline undergoes massive erosion, like a hurricane flattening a beach and its nearby environments, it has to rebuild itself - relying on the resilience of its natural coastal structures to begin piecing itself back together in a way that will allow it to survive the next large phenomena that comes its way.

Drs. Orencio Duran Vinent, assistant professor, and Ignacio Rodriguez-Iturbe, Distinguished University Professor and Wofford Cain Chair I Professor, in the Department of Ocean Engineering at Texas A&M University, are investigating the resilience of barrier ...

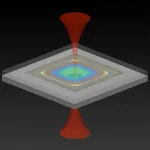

You're going at the speed limit down a two-lane road when a car barrels out of a driveway on your right. You slam on the brakes, and within a fraction of a second of the impact an airbag inflates, saving you from serious injury or even death.

The airbag deploys thanks to an accelerometer -- a sensor that detects sudden changes in velocity. Accelerometers keep rockets and airplanes on the correct flight path, provide navigation for self-driving cars, and rotate images so that they stay right-side up on cellphones and tablets, among other essential tasks.

Addressing the increasing ...