(Press-News.org) (LOS ANGELES) - Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most prevalent chronic liver disease worldwide. It is found in 30% of people in developed countries and occurs in approximately 25% of people in the United States. Risk factors for the disease include obesity, diabetes, high cholesterol and poor eating habits, although this does not exclude individuals without these risk factors.

There is normally a small amount of fat found in the liver; however, if the amount of fat makes up 5% or more of the liver, this is considered to be NAFLD and it must be managed to avoid serious disease progression. In its worst-case scenario, NAFLD can result in swelling and inflammation of the liver, fibrosis, or scarring, of the liver, liver failure or liver cancer.

The liver is a complex organ, and the physiological events involved in NAFLD progression involve multiple steps and different kinds of cells found in the liver. Abnormal accumulation of fatty acids in the liver triggers immune cells called Kupffer cells, as well as endothelial cells lining the liver's blood vessels, to release both signaling and chemically reactive molecules. These molecules stimulate cells called stellate cells to synthesize and deposit fibrosis proteins, which lead to scar formation in the liver.

NAFLD can be managed by a healthy diet and exercise and by losing and/or controlling weight, but there is currently no definitive treatment or cure. One of the main difficulties in developing treatments is that there are no accurate NAFLD models with which to test treatment efficacy. Animal models do not truly represent the steps involved in human NAFLD and human models developed in the past have also shown limitations. A relatively advanced "artificial fibrosis model" to stimulate the final, fibrosis-development part of the disease sequence has been created, but it did not fully correlate with observations of the full disease progression.

A collaborative team from the Terasaki Institute for Biomedical Innovation (TIBI) has developed an advanced, multicellular, structurally representative liver-on-a-chip model which mimics the full progression sequence of NAFLD. The model contains all four types of human primary cells which are involved in the sequence: Kupffer cells, endothelial cells, stellate cells and hepatocytes.

The cells were mixed together and grown as multicellular microtissues in an array of pyramid-shaped microwells; the cell numbers and proportions were adjusted to yield microtissues of optimum shape to maintain nutrient and oxygen concentrations similar to naturally-occurring liver tissues. The microtissues were then enclosed within a gelatinous substance to enable the tissues to more fully match the structure and cell-to-cell interactions of native liver tissues.

The team used their multicellular liver-on-a-chip model in tests designed to validate the role of stellate cells in NAFLD. They concluded that stellate cells appear to be involved with blood vessel formation, production of chemically reactive compounds and to some degree in fatty acid accumulation. They also concluded that stellate cells may interact with Kupffer and other liver cells to produce certain signaling molecules. All these events are crucial components in full NAFLD progression.

The team also tested the effects of fatty acid addition to their model. The results indicated that the presence of fatty acids and active stellate cells accelerated inflammatory responses and increased the production of fibrotic proteins, further validating the model's mimicry of the natural progression of NAFLD.

Subsequent tests compared TIBI's NAFLD model to the previously mentioned artificial fibrosis model driven by transforming growth factor (TGF)-β. When comparing both models, TIBI's fibrosis model mimicked the natural progression of NAFLD by exhibiting higher levels of fat accumulation and fibrosis molecules than in the artificial fibrosis model.

In addition, the team tested the response to anti-fibrotic drugs in both models. The tests demonstrated that TIBI's NAFLD model demonstrated a more robust drug transport and metabolic response upon delivery of the drugs. This finding is significant if the model is to be used for screening of potential drugs for the treatment of NAFLD.

"Our multicellular liver-on-a-chip system is a laboratory model that is more advanced and more fully represents the natural progression of NAFLD than in previous models," said Junmin Lee, Ph.D., a member of the TIBI team. "This is supported by the experimental results from our comparison studies."

It is the hope that TIBI's NAFLD model can be used for elucidating the mechanisms behind this disease and for testing possible drug treatments for efficacy. It also has the potential to personalize treatments by obtaining the full array of cells needed from individual patients and using them to create custom disease models.

"The multicellular model described here is an exemplary demonstration of the level of work that we do in developing personalized physiological models," said Ali Khademhosseini, Ph.D., director and CEO of the Terasaki Institute. "It has the potential for helping to discover treatments for a prevalent and potentially fatal disease."

INFORMATION:

Additional authors are Hyun-Jong Cho, Han-Jun Kim, KangJu Lee, Soufian Lasli, Aly Ung, Tyler Hoffman, Rohollah Nasiri, Praveen Bandaru, Samad Ahadian, Mehmet R Dokmeci and Ali Khademhosseini.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1UG3TR003148-01 and 1R01GM126571-01) and by the Office of the Secretary of Defense under Agreement Number W911NF-17-3-003. It was also funded in part by the Advanced Regenerative Manufacturing Institute, Inc. ("ARMI")

PRESS CONTACT

Stewart Han, shan@terasaki.org,

+1 818-836-4393

Terasaki Institute for Biomedical Innovation

The Terasaki Institute for Biomedical Innovation (terasaki.org) is a non-profit research organization that invents and fosters practical solutions that restore or enhance the health of individuals. Research at the Terasaki Institute leverages scientific advancements that enable an understanding of what makes each person unique, from the macroscale of human tissues down to the microscale of genes, to create technological solutions for some of the most pressing medical problems of our time. We use innovative technology platforms to study human disease on the level of individual patients by incorporating advanced computational and tissue-engineering methods. Findings yielded by these studies are translated by our research teams into tailored diagnostic and therapeutic approaches encompassing personalized materials, cells and implants with unique potential and broad applicability to a variety of diseases, disorders and injuries.

The Institute is made possible through an endowment from the late Dr. Paul I Terasaki, a pioneer in the field of organ transplant technology.

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - New contact lens technology to help diagnose and monitor medical conditions may soon be ready for clinical trials.

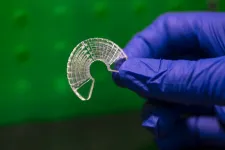

A team of researchers from Purdue University worked with biomedical, mechanical and chemical engineers, along with clinicians, to develop the novel technology. The team enabled commercial soft contact lenses to be a bioinstrumentation tool for unobtrusive monitoring of clinically important information associated with underlying ocular health conditions.

The team's work is published in Nature Communications. The Purdue Research Foundation Office of Technology Commercialization helped secure a patent for the technology and it is available ...

Armando Collazo Garcia III got more than he expected from a graduate course he took last spring. He developed a new understanding of the physics of transonic shocks produced across a laminar flow airfoil with boundary-layer suction and added a published paper to his resume.

"When I got the assignment to do a research project, I realized I already had a good data set from my master's thesis that I could use in a new way," Collazo Garcia said. "I was able to apply linear algebra techniques to manipulate the flow field data and decompose the information into modes. The modes provided a snapshot of various aspects of the flow and were ranked by their energy contribution, ...

Scientists have used modern genetic techniques to prove age-old assumptions about what sizes of fish to leave in the sea to preserve the future of local fisheries.

"We've known for decades that bigger fish produce exponentially more eggs," said the lead author of the new study, Charles Lavin, who is a research fellow from James Cook University (JCU) and Nord University in Norway.

"However, we also found while these big fish contributed significantly to keeping the population going--they are also rare."

Co-author Dr Hugo Harrison from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies ...

New international research published in Anaesthesia (a journal of the Association of Anaesthetists) concludes that surgery should be delayed for seven weeks after a patient tests positive for SARS-CoV-2, since the data show that surgery that takes place between 0 and 6 weeks after diagnosis is associated with increased mortality.

The study is by the COVIDSurg Collaborative: a global collaboration of over 15,000 surgeons working together to collect a range of data on the COVID-19 pandemic. This study's lead authors are Dr Dmitri Nepogodiev (Public Health) and Dr Aneel Bhangu (Surgeon) of the University of Birmingham, UK.

While it is known that infection with SARS-CoV-2 during surgery increases mortality and international guidelines recommend ...

Over the summer and fall, paper after paper revealed that mothers are one of the demographics hardest hit by the pandemic. From layoffs and leaving careers to do caretaking, to submission rate decreases and additional service projects, the data were clear, but the follow up less so. Many of the problems are not new and will remain after the pandemic. But a new paper, published this week in PLOS Biology, outlines methods to help solve them.

"In the spirit of the well-worn adage 'never let a good crisis go to waste,' we propose using these unprecedented times as a springboard for necessary, substantive and lasting change," write the 13 co-authors, led by researchers from Boston University and hailing from seven institutions, ...

Language difficulties and cultural barriers keep an "alarming" number of Chinese Americans from asking for cancer screenings that may protect their health, according to a new University of Central Florida study.

Su-I Hou, professor and interim chair of UCF's Health Management & Informatics Department, said her results show that physicians and members of the Chinese community need to improve their communication about the importance of cancer screenings. Her study was recently published in the Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention.

Hou surveyed 372 ...

PHILADELPHIA (March 9, 20201) - The PhD degree prepares nurse scientists to advance knowledge through research that improves health, translates into policy, and enhances education. However, as the role of the nurse has changed, and health care has grown more complex, there is a need to re-envision how PhD programs can attract, retain, and create the nurse-scientists of the future and improve patient care.

To begin the dialog about the future of PhD education in research-intensive schools, the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing (Penn Nursing) invited 41 educational, governmental, professional, and philanthropic institutions to ...

MIAMI--In the Florida Straits at night, and under a new moon is the preference for spawning mahi-mahi, according to a new study by scientists at the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science.

These new details on the daily life of the highly sought-after migratory fish can help better manage their populations and provide scientists with new information to understand the impacts to the animal from changing environmental conditions.

To uncover these important details about the behaviors of mahi-mahi, or dolphinfish, the research team tagged captive spawning ...

WOODS HOLE, Mass. -- A long-lasting, successful relationship between scientists at the MBL Ecosystems Center and the citizen-led Buzzards Bay Coalition has garnered a long-term record of water quality in the busy bay that lies west of Woods Hole. That record has already returned tremendous value and last week, it was published in Scientific Data, a Nature journal.

"We hope getting this data out will encourage scientists to use it to test new hypotheses and develop new insights into Bay health," said Rachel Jakuba, science director of the Buzzards Bay Coalition and lead author of the journal article.

Since 1992, a large and dedicated team of citizen volunteers, dubbed Baywatchers, has been ...

News Release -- LOGAN, UT -- Mar. 9, 2021 -- Researchers at Utah State University are using silkworm silk to grow skeletal muscle cells, improving on traditional methods of cell culture and hopefully leading to better treatments for muscle atrophy.

When scientists are trying to understand disease and test treatments, they generally grow model cells on a flat plastic surface (think petri dish). But growing cells on a two-dimensional surface has its limitations, primarily because muscle tissue is three-dimensional. Thus, USU researchers developed a three-dimensional cell culture surface by growing cells on silk fibers that are wrapped around an acrylic ...