Accurate aging of wild animals thanks to first epigenetic clock for bats

UMD-led research identifies age-related changes to DNA and reveals longevity-related differences between bat species

2021-03-12

(Press-News.org) A new study led by University of Maryland and UCLA researchers found that DNA from tissue samples can be used to accurately predict the age of bats in the wild. The study also showed age-related changes to the DNA of long-lived species are different from those in short-lived species, especially in regions of the genome near genes associated with cancer and immunity. This work provides new insight into causes of age-related declines.

This is the first research paper to show that animals in the wild can be accurately aged using an epigenetic clock, which predicts age based on specific changes to DNA. This work provides a new tool for biologists studying animals in the wild. In addition, the results provide insight into possible mechanisms behind the exceptional longevity of many bat species. The study appears in the March 12, 2021, issue of the journal Nature Communications.

"We hoped that these epigenetic changes would be predictive of age," said Gerald Wilkinson, a professor of biology at UMD and co-lead author of the paper. "But now we have the data to show that instead of having to follow animals over their lifetime to be sure of their age, you can just go out and take a tiny sample of an individual in the wild and be able to know its age, which allows us to ask all kinds of questions we couldn't before."

The researchers looked at DNA from 712 bats of known age, representing 26 species, to find changes in DNA methylation at sites in the genome known to be associated with aging. DNA methylation is a process that switches genes off. It occurs throughout development and is an important regulator for cells. Overall, methylation tends to decrease throughout the genome with age. Using machine learning to find patterns in the data, the researchers found that they could estimate a bat's age to within a year based on changes in methylation at 160 sites in the genome. The data also revealed that very long-lived bat species exhibit less change in methylation overall as they age than shorter-lived bats.

Wilkinson and his team then analyzed the genomes of four bat species--three long-lived and one short-lived--to identify the specific genes present in those regions of the genome where age-related differences in methylation correlated with longevity. They found specific sites on the genome where methylation was more likely to increase rather than decrease with age in the short-lived bats, but not in long-lived bats, and that those sites were located near 57 genes that mutate frequently in cancerous tumors and 195 genes involved in immunity.

"What's really interesting is that the sites where we found methylation increasing with age in the short-lived bats are near genes that have been shown to be involved in tumorigenesis--cancer--and immune response," Wilkinson said. "This suggests there may be something to look at in these regions regarding mechanisms responsible for longevity."

Wilkinson said analyzing methylation may provide insight into many age-related differences between species and lead to a better understanding of the causes for age-related declines across many species.

"Bats live a long time, and yet their hearing doesn't decay with age, the way ours does," he said. "You could use this method to see whether there are differences in methylation that are associated with hearing. There are all kinds of questions like this we can ask now."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Wilkinson, co-authors of the paper from UMD include current postdoctoral associate Danielle M. Adams (Ph.D. '19, biological sciences) and former graduate students Bryan Arnold (Ph.D. '11, behavior, ecology, evolution, and systematics), now an associate professor at Illinois College; and Gerald Carter (Ph.D., '15, biology), now an assistant professor at Ohio State University; Edward Hurme (Ph.D. '20, biological sciences), now a postdoctoral associate at the University of Konstanz in Germany.

The research paper, "DNA methylation predicts age and provides insight into exceptional longevity of bats," was published in the March 12, 2021, issue of Nature Communications.

This work was supported by a grant from the Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group. The content of this article does not necessarily reflect the view of this organization.

Media Relations Contact: Kimbra Cutlip, 301-405-9463, kcutlip@umd.edu

University of Maryland

College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

2300 Symons Hall

College Park, Md. 20742

http://www.cmns.umd.edu

@UMDscience

About the College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

The College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences at the University of Maryland educates more than 9,000 future scientific leaders in its undergraduate and graduate programs each year. The college's 10 departments and more than a dozen interdisciplinary research centers foster scientific discovery with annual sponsored research funding exceeding $200 million.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-12

Osaka, Japan - Scientists from the Institute of Scientific and Industrial Research at Osaka University fabricated nanopores in silicon dioxide, that were only 300 nm, in diameter surrounded by electrodes. These nanopores could prevent particles from entering just by applying a voltage, which may permit the development of sensors that can detect very small concentrations of target molecules, as well as next-generation DNA sequencing technology.

Nanopores are tiny holes that are wide enough for just a single molecule or particle to pass through. The motion of nanoparticles through these holes ...

2021-03-12

Researchers at UCL have solved a major piece of the puzzle that makes up the ancient Greek astronomical calculator known as the Antikythera Mechanism, a hand-powered mechanical device that was used to predict astronomical events.

Known to many as the world's first analogue computer, the Antikythera Mechanism is the most complex piece of engineering to have survived from the ancient world. The 2,000-year-old device was used to predict the positions of the Sun, Moon and the planets as well as lunar and solar eclipses.

Published in Scientific Reports, the paper from the multidisciplinary UCL Antikythera Research Team reveals a new display ...

2021-03-12

PHILADELPHIA -- (March 12, 2021) -- Scientists at The Wistar Institute identified a new function of ADAR1, a protein responsible for RNA editing, discovering that the ADAR1p110 isoform regulates genome stability at chromosome ends and is required for continued proliferation of cancer cells. These findings, reported in Nature Communications, reveal an additional oncogenic function of ADAR1 and reaffirm its potential as a therapeutic target in cancer.

The lab of Kazuko Nishikura, Ph.D., professor in the Gene Expression & Regulation Program of The Wistar Institute Cancer Center, was one of the first to discover ADAR1 in mammalian cells and to characterize the process of RNA editing ...

2021-03-12

A factor that turns malignant tumors into benign ones? - That is exactly what scientists at St. Anna Children's Cancer Research Institute have discovered. Together with colleagues from the Medical University of Vienna and the University of Vienna (Faculty of Chemistry), they studied tumors of the peripheral nervous system in children, namely neuroblastomas. The scientists discovered that the uncontrolled growth of benign neuroblastomas is stopped by a signal molecule produced by Schwann cells present within these tumors. This natural "brake" also works on malignant neuroblastoma ...

2021-03-12

Brominated flame retardants (BFRs) are found in furniture, electronics, and kitchenware to slow the spread of flames in the event of a fire. However, it has been shown that these molecules may lead to early mammary gland development, which is linked to an increased risk of breast cancer. The study on the subject by Professor Isabelle Plante from the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS) made the cover of the February issue of the journal Toxicological Sciences.

Part of the flame retardants are considered to be endocrine disruptors, i.e. they interfere with the hormonal system. Since they are not directly bound to the material in which they are added, the molecules escape easily. They are then found in house ...

2021-03-12

Chest pain is misdiagnosed in women more frequently than in men, according to research presented today at ESC Acute CardioVascular Care 2021, an online scientific congress of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).1 The study also found that women with chest pain were more likely than men to wait over 12 hours before seeking medical help.

"Our findings suggest a gender gap in the first evaluation of chest pain, with the likelihood of heart attack being underestimated in women," said study author Dr. Gemma Martinez-Nadal of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Spain. "The low suspicion of heart attack occurs in both women themselves and in physicians, leading to higher risks of late diagnosis and misdiagnosis."

This study examined gender differences in the presentation, ...

2021-03-11

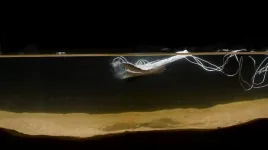

As gatherings to observe whooping cranes join the ranks of online-only events this year, a new study offers insight into how the endangered bird is faring on a landscape increasingly dotted with wind turbines. The paper, published this week in Ecological Applications, reports that whooping cranes migrating through the U.S. Great Plains avoid "rest stop" sites that are within 5 km of wind-energy infrastructure.

Avoidance of wind turbines can decrease collision mortality for birds, but can also make it more difficult and time-consuming for migrating flocks to find safe and suitable rest and refueling locations. The study's insights into migratory behavior ...

2021-03-11

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Overweight low-income mothers of young kids ate fewer fast-food meals and high-fat snacks after participating in a study - not because researchers told them what not to eat, but because the lifestyle intervention being evaluated helped lower the moms' stress, research suggests.

The 16-week program was aimed at preventing weight gain by promoting stress management, healthy eating and physical activity. The methods to get there were simple steps tucked into lessons on time management and prioritizing, many demonstrated in a series ...

2021-03-11

In the field of robotics, metals offer advantages like strength, durability, and electrical conductivity. But, they are heavy and rigid--properties that are undesirable in soft and flexible systems for wearable computing and human-machine interfaces.

Hydrogels, on the other hand, are lightweight, stretchable, and biocompatible, making them excellent materials for contact lenses and tissue engineering scaffolding. They are, however, poor at conducting electricity, which is needed for digital circuits and bioelectronics applications.

Researchers in Carnegie Mellon University's Soft Machines Lab have developed a unique silver-hydrogel composite that has high electrical ...

2021-03-11

Crabs are living the meme life on social media lately. The memes joke that everything will eventually look like a crab. But it's actually based in some truth.

The crab shape has evolved so many times the evolutionary biologist L.A. Borradaile coined the term carcinization in 1916 to describe the convergent evolution process in which a crustacean evolves into a crab-like form from a non-crab-like form. Crabs are decapod crustaceans of the infraorder Brachyura and are considered "true crabs", most of which are carcinized. "False crabs" are of the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Accurate aging of wild animals thanks to first epigenetic clock for bats

UMD-led research identifies age-related changes to DNA and reveals longevity-related differences between bat species