(Press-News.org) BOSTON - Researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have uncovered new clues that add to the growing understanding of how female mammals, including humans, "silence" one X chromosome. Their new study, published in Molecular Cell, demonstrates how certain proteins alter the "architecture" of the X chromosome, which contributes to its inactivation. Better understanding of X chromosome inactivation could help scientists figure out how to reverse the process, potentially leading to cures for devastating genetic disorders.

Female mammals have two copies of the X chromosome in all of their cells. Each X chromosome contains many genes, but only one of the pair can be active; if both X chromosomes expressed genes, the cell couldn't survive. To prevent both X chromosomes from being active, female mammals have a mechanism that inactivates one of them during development. X chromosome inactivation is orchestrated by a noncoding form of RNA called Xist, which silences genes by spreading across the chromosome, recruiting other proteins (such as Polycomb repressive complexes) to complete the task.

Jeannie Lee, MD, PhD, an investigator in the Department of Molecular Biology at MGH and the paper's senior author, has led pioneering research on X chromosome inactivation. She believes that understanding the phenomenon could lead to cures for congenital diseases known as X-linked disorders, which are caused by mutations in genes on the active X chromosome. "Our goal is to reactivate the inactive X chromosome, which carries a good copy of the gene," says Lee. Doing so could have profound benefits for people with conditions such as Rett syndrome, a disorder brought on by a mutation in a gene called MECP2 that almost always occurs in girls and causes severe problems with language, learning, coordination and other brain functions. In theory, reactivating the X chromosome could cure Rett syndrome and other X-linked disorders.

In this study, Lee and Andrea Kriz, a PhD student and first author of the paper, were interested in understanding the role of clusters of proteins called cohesins in X inactivation. Cohesins are known to play a critical role in gene expression. Imagine a chromosome as a long piece of string with genes and their regulatory sequences being far apart, says Lee. For the gene to be turned "on" and do its job, such as producing a specific protein, it has to come in contact with its distant regulator. Chromosomes allow this to happen by forming a small loop that brings together the gene and regulator. Ring-shaped cohesins help these loops form and stabilize. When the gene's work is done and it's time to turn off, a scissor-like protein called WAPL snips it, causing the gene to disconnect from its regulator. An active chromosome has many of these loops, which are continually forming and dissociating (or separating).

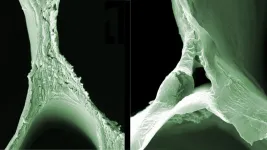

These small loops, which are essential for gene expression, are relatively suppressed on an inactivated X chromosome. One reason, as Lee and her colleagues have already shown, is that Xist "evicts" most cohesins from the inactive X chromosome and that this cohesin depletion may be necessary to reorganize the shape and structure of the chromosome for silencing.

In the current study, Lee and Kriz used embryonic stem cells from female mice to find out what happens when cohesin or WAPL levels are manipulated during X chromosome inactivation by using protein-degradation technology. "We found that if cohesin levels build up too high, the X chromosome cannot inactivate properly," says Lee. Normally, retaining cohesins (which are normally supposed to be evicted) prevented the X chromosome from folding into an inactive shape and gene silencing was affected. "You need a fine balance between eviction and retention of cohesins during X chromosome inactivation," says Lee.

Next, the authors asked what happens when cohesin is manipulated in an active X chromosome. The short answer: It takes on some peculiar qualities of an inactivated X chromosome. First, when there is insufficient cohesin, the active X develops structures called "superloops" that are usually only seen on the inactive X. Second, when there is too much cohesin, the active X develops "megadomains," which Lee calls two "big blobs," and are also ordinarily unique to the inactive X. "The fact that we can confer some features of the inactive X chromosome onto the active X chromosome just by toggling cohesin levels is intriguing," says Lee. She and her colleagues are trying to understand how and why that happens.

These findings suggests that shape and structure of the X chromosome play a vital role in allowing Xist to spread from one side to the other and achieve inactivation. "The more we learn about what's important for silencing the X chromosome," says Lee, "the more likely we'll be to find ways to reactivate it and to treat conditions like Rett syndrome."

INFORMATION:

Lee is director of the Lee Laboratory at MGH, vice chair of Molecular Biology, and a professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School.

About the Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The Mass General Research Institute conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the nation, with annual research operations of more than $1 billion and comprises more than 9,500 researchers working across more than 30 institutes, centers and departments. In August 2020, Mass General was named #6 in the U.S. News & World Report list of "America's Best Hospitals."

Ingo Burgert and his team at Empa and ETH Zurich has proven it time and again: Wood is so much more than "just" a building material. Their research aims at extending the existing characteristics of wood in such a way that it is suitable for completely new ranges of application. For instance, they have already developed high-strength, water-repellent and magnetizable wood. Now, together with the Empa research group of Francis Schwarze and Javier Ribera, the team has developed a simple, environmentally friendly process for generating electricity from a type of wood sponge, as they reported last week in the journal Science Advances.

Voltage through deformation

If you want to generate electricity ...

AUSTIN, Texas -- Using NASA satellite images and machine learning, researchers with The University of Texas at Austin have mapped changes in the landscape of northwestern Belize over a span of four decades, finding significant losses of forest and wetlands, but also successful regrowth of forest in established conservation zones that protect surviving structures of the ancient Maya.

The research serves as a case study for other rapidly developing and tropical regions of the globe, especially in places struggling to balance forest and wetland conservation with agricultural needs and food security.

"Broad-scale global studies show that tropical deforestation and wetland destruction is occurring ...

Modeling - Urban climate impacts

Researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory have identified a statistical relationship between the growth of cities and the spread of paved surfaces like roads and sidewalks. These impervious surfaces impede the flow of water into the ground, affecting the water cycle and, by extension, the climate.

"We've shown that there is a specific mathematical shape to the relationship between a city's population and the total paved area," ORNL's Christa Brelsford said. "Using that, we examined climate model predictions and determined they correctly represent some important attributes ...

In order to withstand the rigors of space on deep-space missions, food grown outside of Earth needs a little extra help from bacteria. Now, a recent discovery aboard the International Space Station (ISS) has researchers may help create the 'fuel' to help plants withstand such stressful situations.

Publishing their findings to END ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Women veterinarians make less than their male counterparts, new research from Cornell University's College of Veterinary Medicine has found ¬- with an annual difference of around $100,000 among the top quarter of earners.

The disparity predominantly affects recent graduates and the top half of earners, according to the research, the first overarching study of the wage gap in the veterinary industry.

"Veterinarians can take many paths in their careers, all of which affect earning potential," said the paper's senior author, Dr. Clinton Neill, assistant professor in the Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences.

"Similar to what's been found in the human medicine world, we found the wage gap was more prominent ...

Do children learning French as a second language see benefits from reading bilingual French-English children's books?

A study recently published in the journal Language and Literacy found that bilingual books, which are not often used in French immersion classrooms, are seen by students as an effective tool for second language learning.

To find out more on this topic, we spoke with the co-author of the paper, Joël Thibeault, Assistant Professor of French education at uOttawa's Faculty of Education.

What is the topic of your research?

"My research focuses on the educational value of bilingual children's books in the teaching of French as a second language. To highlight this value, I zeroed in on elementary students in French immersion ...

Drugs can only work if they stick to their target proteins in the body. Assessing that stickiness is a key hurdle in the drug discovery and screening process. New research combining chemistry and machine learning could lower that hurdle.

The new technique, dubbed DeepBAR, quickly calculates the binding affinities between drug candidates and their targets. The approach yields precise calculations in a fraction of the time compared to previous state-of-the-art methods. The researchers say DeepBAR could one day quicken the pace of drug discovery and protein engineering.

"Our method is orders of magnitude faster than before, meaning we can have drug discovery that is both efficient and reliable," ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - If you count yourself among those who lose themselves in the lives of fictional characters, scientists now have a better idea of how that happens.

Researchers found that the more immersed people tend to get into "becoming" a fictional character, the more they use the same part of the brain to think about the character as they do to think about themselves.

"When they think about a favorite fictional character, it appears similar in one part of the brain as when they are thinking about themselves," said Timothy Broom, lead author of the study and doctoral student in psychology at The Ohio State University.

The study was published ...

Statewide stay-at-home orders put in place as Tennessee fought to control the spread of coronavirus last March were associated with a 14% lower rate of preterm birth, according to a research letter published today in JAMA Pediatrics.

Preterm infants have higher morbidity and mortality risks than babies born at term.

Senior author Stephen Patrick, MD, director of the Vanderbilt Center for Child Health Policy and a neonatologist at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt and his colleagues had observed in March that there appeared to be fewer infants than usual in the NICU at ...

A home-based parenting programme to prevent childhood behaviour problems, which very unusually focuses on children when they are still toddlers and, in some cases, just 12 months old, has proven highly successful during its first public health trial.

The six-session programme involves providing carefully-prepared feedback to parents about how they can build on positive moments when playing and engaging with their child using video clips of everyday interactions, which are filmed by a health professional while visiting their home.

It was trialled with 300 families of children who had shown early signs of behaviour problems. Half of the families received the programme alongside routine ...