INFORMATION:

The American Society for Microbiology is one of the largest professional societies dedicated to the life sciences and is composed of 30,000 scientists and health practitioners. ASM's mission is to promote and advance the microbial sciences.

ASM advances the microbial sciences through conferences, publications, certifications, educational opportunities and advocacy efforts. It enhances laboratory capacity around the globe through training and resources. It provides a network for scientists in academia, industry and clinical settings. Additionally, ASM promotes a deeper understanding of the microbial sciences to diverse audiences.

Multidrug-resistant candida auris discovered in a natural environment

2021-03-16

(Press-News.org) Washington, D.C. - March 16, 2021 - For the first time, researchers have isolated the fungus Candida auris from a sandy beach and tidal swamp in a remote coastal wetland ecosystem. The discovery, reported this week in mBio, an open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology, represents the first evidence that the pathogen thrives in a natural environment and is not limited to mammalian hosts. C. auris can cause infections resistant to major antifungal drugs, and since its identification in clinical patients 10 years ago scientists have sought to understand its origins.

A commentary accompanying the study, published concurrently in the journal, hailed the work as a "landmark discovery."

Medical mycologist Anuradha Chowdhary, Ph.D, at the University of Delhi, in India, led the new study. She and her colleagues analyzed 48 samples of soil and water collected from 8 sites including rocky shores, sandy beaches, tidal marshes, and mangrove swamps around the Andaman Islands, an isolated archipelago with a tropical climate in the Bay of Bengal. They isolated C. auris in the samples from two sites, a bay tidal salt marsh wetland and a beach.

In samples from the salt marsh, which was rich in seagrass and low in human activity, the researchers found 2 isolates, one of which proved to be multidrug susceptible when tested against antifungals. In samples from the beach, which was high in human activity, the team identified 22 isolates, all of which were multidrug resistant. Whole genome sequencing of the isolates revealed that they were closely related to pathogenic strains found in Southeast Asia.

"The isolates?found in the area where there was human activity were more related to strains we see in the clinical setting," Chowdhary said. Future studies, she said, may be able to explain that connection. "It might be coming from plants, or might be shed from human skin, which we know C. auris can colonize. We need to explore more environmental niches for the pathogen."

Although cases of C. auris trace to the mid-1990s, the fungus wasn't named until 2009.

The new work also provides evidence for a hypothesis recently introduced by the microbiologists who authored the new commentary, including Arturo Casadevall, Ph.D, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore; Dimitrios Kontoyiannis, Ph.D, of the The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston; and Vincent Robert, Ph.D, Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, in Utrecht, Netherlands.

The trio proposed that C. auris, which is tolerant to a range of temperatures and salinity, is native to wetlands, and its emergence as a pathogen in humans has resulted from global warming effects on those environments. Chowdhary, who has been studying C. auris for nearly a decade, said that hypothesis inspired her to explore ecological niches where the fungus might live.

"This study takes the first step in toward understanding how pathogen survives in the wetland," Chowdhary said, "but this is just one niche." Future studies, she said, could reveal more about how the fungus thrives in the wild--and better explain why it's such a menace to humans.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Pick up the pace!

2021-03-16

SLOW walkers are almost four times more likely to die from COVID-19, and have over twice the risk of contracting a severe version of the virus, according to a team of researchers from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Leicester Biomedical Research Centre led by Professor Tom Yates at the University of Leicester.

The study of 412,596 middle-aged UK Biobank participants examined the relative association of body mass index (BMI) and self-reported walking pace with the risk of contracting severe COVID-19 and COVID-19 mortality.

The analysis found slow walkers of a normal weight to be almost 2.5 times more likely to develop severe COVID-19 and 3.75 times more likely to die from the virus ...

BIDMC researchers model a safe new normal

2021-03-16

Boston, Mass. - Just one year after the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus a global pandemic, three COVID-19 vaccines are available in the United States, and more than 2 million Americans are receiving shots each day. Americans are eager to get back to business as usual, but experts caution that opening the economy prematurely could allow a potential resurgence of the virus. How foot traffic patterns in restaurants and bars, schools and universities, nail salons and barbershops affect the risk of transmission has been largely unknown.

In an article published ...

Leprosy drug holds promise as at-home treatment for COVID-19

2021-03-16

LA JOLLA, CALIF. - March 16, 2021 - A Nature study authored by scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute and the University of Hong Kong shows that the leprosy drug clofazimine, which is FDA approved and on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, exhibits potent antiviral activities against SARS-CoV-2 and prevents the exaggerated inflammatory response associated with severe COVID-19. Based on these findings, a Phase 2 study evaluating clofazimine as an at-home treatment for COVID-19 could begin immediately.

"Clofazimine is an ideal candidate for a COVID-19 treatment. It is safe, affordable, easy to make, taken as a pill and can be made globally available," ...

More accurate method to predict long term outcomes for pre-invasive breast cancer

2021-03-16

A study by Queen Mary University of London researchers, funded by Cancer Research UK, confirms the role of the oestrogen receptor biomarker in ductal carcinoma in situ and presents a new and more accurate method to predict long term outcomes for this pre-invasive stage of breast cancer. The study is published in Clinical Cancer Research.

Oestrogen receptor (ER), a protein expressed in some breast cancer cells, is routinely tested in invasive breast cancer to predict long-term outcomes select treatment options. Its role in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) has been previously unclear, and it is not generally evaluated in this pre-invasive stage of breast cancer. The new research confirms the role of ER in predicting ...

Electronic cigarettes help smokers with schizophrenia quit

2021-03-16

A new study in Nicotine & Tobacco Research, published by Oxford University Press, finds that the use of high-strength nicotine e-cigarettes can help adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders quit smoking.

Some 60-90% of people with schizophrenia smoke cigarettes, compared to 15-24% of the general population. The researchers from the University of Catania, in collaboration with colleagues from City University of New York and Weill Medical College of Cornell University, have assessed here the feasibility of using a high-strength nicotine e-cigarette to modify smoking behavior in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders who smoke cigarettes. In this study ...

A promising breakthrough for a better design of electronic materials

2021-03-16

Finding the best materials for tomorrow's electronics is the goal of Professor Emanuele Orgiu of the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS). Among the materials in which Professor Orgiu is interested, some are made of molecules that can conduct electricity. He has demonstrated the role played by molecular vibrations on electron conductivity on crystals of such materials. This finding is important for applications of these molecular materials in electronics, energy and information storage. The study, conducted in collaboration with a team from the INRS and the ...

Non-invasive skin swab samples are enough to quickly detect COVID-19, a new study finds

2021-03-16

Researchers at the University of Surrey have found that non-invasive skin swab samples may be enough to detect COVID-19.

The most widely used approach to testing for COVID-19 requires a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, which involves taking a swab of the back of the throat and far inside the nose.

In a paper published by Lancet E Clinical Medicine, chemists from Surrey teamed up with Frimley NHS Trust and the Universities of Manchester and Leicester to collect sebum samples from 67 hospitalised patients - 30 who had tested positive for COVID-19 and 37 who had tested negative. The samples were collected by gently swabbing a skin area rich in sebum - an oily, waxy substance produced by the body's sebaceous glands - such as the face, neck or back.

The researchers analysed ...

Abuse in childhood and adolescence linked to higher likelihood of conduct problems

2021-03-16

Children who are exposed to abuse before they are eleven years old, and those exposed to abuse both in childhood and adolescence may be more likely to develop conduct problems (such as bullying or stealing) than those exposed to abuse in adolescence only and those who are not exposed to abuse, according to a study published in the open access journal BMC Psychiatry.

A team of researchers at the Universities of Bath and Bristol examined data on 13,793 children and adolescents (51.6% boys), who were followed from ages four to 17 years, included in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, ...

Use of AI to fight COVID-19 risks harming 'disadvantaged groups', experts warn

2021-03-16

Rapid deployment of artificial intelligence and machine learning to tackle coronavirus must still go through ethical checks and balances, or we risk harming already disadvantaged communities in the rush to defeat the disease.

This is according to researchers at the University of Cambridge's Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence (CFI) in two articles, published today in the British Medical Journal, cautioning against blinkered use of AI for data-gathering and medical decision-making as we fight to regain some normalcy in 2021.

"Relaxing ...

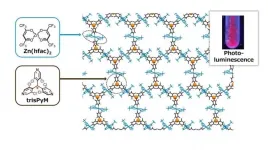

A novel recipe for air-stable and highly-crystalline radical-based coordination polymer

2021-03-16

Coordination polymers (CPs) composed of organic radicals have been the focus of much research attention in recent years due to their potential application to a wide variety of next-generation electronics, from more flexible devices to 'spintronics' storage of information. Sadly, they often suffer from their limited stability and poor crystallinity. Researchers from Japan's Institute for Molecular Science (IMS), National Institute of Natural Sciences (NINS) have developed a novel recipe that not only produces a stable material, but offers a variety of other useful attributes.

Their findings appear in the journal ...