(Press-News.org) SAN FRANCISCO (March 16, 2021) - Over the course of Earth's history, several mass extinction events have destroyed ecosystems, including one that famously wiped out the dinosaurs. But none were as devastating as "The Great Dying," which took place 252 million years ago during the end of the Permian period. A new study, published today in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, shows in detail how life recovered in comparison to two smaller extinction events. The international study team--composed of researchers from the China University of Geosciences, the California Academy of Sciences, the University of Bristol, Missouri University of Science and Technology, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences--showed for the first time that the end-Permian mass extinction was harsher than other events due to a major collapse in diversity.

To better characterize "The Great Dying," the team sought to understand why communities didn't recover as quickly as other mass extinctions. The main reason was that the end-Permian crisis was much more severe than any other mass extinction, wiping out 19 out of every 20 species. With survival of only 5% of species, ecosystems had been destroyed, and this meant that ecological communities had to reassemble from scratch.

To investigate, lead author and Academy researcher Yuangeng Huang, now at the China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, reconstructed food webs for a series of 14 life assemblages spanning the Permian and Triassic periods. These assemblages, sampled from north China, offered a snapshot of how a single region on Earth responded to the crises. "By studying the fossils and evidence from their teeth, stomach contents, and excrement, I was able to identify who ate whom," says Huang. "It's important to build an accurate food web if we want to understand these ancient ecosystems."

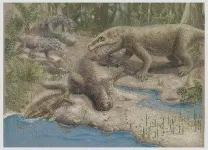

The food webs are made up of plants, molluscs, and insects living in ponds and rivers, as well as the fishes, amphibians, and reptiles that eat them. The reptiles range in size from that of modern lizards to half-ton herbivores with tiny heads, massive barrel-like bodies, and a protective covering of thick bony scales. Sabre-toothed gorgonopsians also roamed, some as large and powerful as lions and with long canine teeth for piercing thick skins. When these animals died out during the end-Permian mass extinction, nothing took their place, leaving unbalanced ecosystems for ten million years. Then, the first dinosaurs and mammals began to evolve in the Triassic. The first dinosaurs were small--bipedal insect-eaters about one meter long--but they soon became larger and diversified as flesh- and plant-eaters.

"Yuangeng Huang spent a year in my lab," says Peter Roopnarine, Academy Curator of Geology. "He applied ecological modelling methods that allow us to look at ancient food webs and determine how stable or unstable they are. Essentially, the model disrupts the food web, knocking out species and testing for overall stability."

"We found that the end-Permian event was exceptional in two ways," says Professor Mike Benton from the University of Bristol. "First, the collapse in diversity was much more severe, whereas in the other two mass extinctions there had been low-stability ecosystems before the final collapse. And second, it took a very long time for ecosystems to recover, maybe 10 million years or more, whereas recovery was rapid after the other two crises."

Ultimately, characterizing communities--especially those that recovered successfully--provides valuable insights into how modern species might fare as humans push the planet to the brink.

"This is an amazing new result," says Professor Zhong-Qiang Chen of the China University of Geosciences, Wuhan. "Until now, we could describe the food webs, but we couldn't test their stability. The combination of great new data from long rock sections in North China with cutting-edge computational methods allows us to get inside these ancient examples in the same way we can study food webs in the modern world."

INFORMATION:

(Vienna, March 17, 2021) When complex systems double in size, many of their parts do not. Characteristically, some aspects will grow by only about 80 percent, others by about 120 percent. The astonishing uniformity of these two growth rates is known as "scaling laws." Scaling laws are observed everywhere in the world, from biology to physical systems. They also apply to cities. Yet, while a multitude of examples show their presence, reasons for their emergence are still a matter of debate.

A new publication in the Journal of The Royal Society Interface now provides a simple explanation for urban scaling laws: Carlos Molinero and Stefan Thurner of the Complexity Science Hub Vienna (CSH) derive them from the geometry of a city.

Scaling laws in ...

The UK variant of SARS-CoV-2 spread rapidly in care homes in England in November and December last year, broadly reflecting its spread in the general population, according to a study by UCL researchers.

The study, published as a letter in the New England Journal of Medicine, looked at positive PCR tests of care home staff and residents between October and December. It found that, among the samples it had access to, the proportion of infections caused by the new variant rose from 12% in the week beginning 23 November to 60% of positive cases just two weeks later, in the week beginning 7 December.

In the south east of England, where the variant was most dominant, the proportion increased from 55% to 80% over the same period. In London, where the variant spread fastest, ...

Washington, DC, March 16, 2021 - A study in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (JAACAP), published by Elsevier, reports on the young adult assessment of the now 20-year longitudinal Boricua Youth Study (BYS), a large cohort that brings much needed insight about development and mental health of children from diverse ethnic background growing up in disadvantaged contexts.

The present article, with its companion report on prevalence of conditions and associated factors, provides an update on the study's fourth wave, which follows-up two probability-based population samples of children of Puerto Rican heritage. ...

Certain brightly colored coral species dotting the seafloor may appear indistinguishable to many divers and snorkelers, but Florida State University researchers have found that these genetically diverse marine invertebrates vary in their response to ocean warming, a finding that has implications for the long-term health of coral reefs.

The researchers used molecular genetics to differentiate among corals that look nearly identical and to understand which species best coped with thermal stress. Their research was published in the journal Ecology.

"Being able to recognize the differences among these coral species that cannot be identified in the field -- which are known as 'cryptic species' -- will help us understand new ways ...

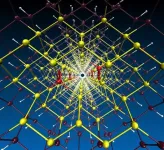

The electron is one of the fundamental particles in nature we read about in school. Its behavior holds clues to new ways to store digital data.

In a study published in Nano Letters, physicists from Michigan Technological University explore alternative materials to improve capacity and shrink the size of digital data storage technologies. Ranjit Pati, professor of physics at Michigan Tech, led the study and explains the physics behind his team's new nanowire design.

"Thanks to a property called spin, electrons behave like tiny magnets," Pati said. "Similar to how a bar magnet's magnetization is dipolar, pointing from south to north, ...

The Volcano Alert Level (VAL) system, standardized by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in 2006, is meant to save lives and keep citizens living in the shadow of an active volcano informed of their current level of risk.

A new study published in Risk Analysis suggests that, when an alert remains elevated at any level above "normal" due to a period of volcanic unrest, it can cause a decline in the region's housing prices and other economic indicators. Because of this, the authors argue that federal policymakers may need to account for the effects of prolonged volcanic unrest -- not just destructive eruptions -- in the provision of disaster relief funding.

A team of geoscientists and statistical experts examined the historical relationship ...

As researchers push the boundaries of battery design, seeking to pack ever greater amounts of power and energy into a given amount of space or weight, one of the more promising technologies being studied is lithium-ion batteries that use a solid electrolyte material between the two electrodes, rather than the typical liquid.

But such batteries have been plagued by a tendency for branch-like projections of metal called dendrites to form on one of the electrodes, eventually bridging the electrolyte and shorting out the battery cell. Now, researchers at MIT and elsewhere have found ...

Even though a fruit fly doesn't have ears, it can hear with its antennae. In a END ...

The first known study to explore optimal outpatient exam scheduling given the flexibility of inpatient exams has resulted in shorter wait times for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) patients at END ...

FINDINGS

A new UCLA study shows that while men and women who have high muscle mass are less likely to die from heart disease, it also appears that women who have higher levels of body fat -- regardless of their muscle mass -- have a greater degree of protection than women with less fat.

The researchers analyzed national health survey data collected over a 15-year period and found that heart disease-related death in women with high muscle mass and high body fat was 42% lower than in a comparison group of women with low muscle mass and low body fat. However, women who had high muscle mass and low ...