INFORMATION:

Prof. Sarel-Jacob Fleishman's research is supported by the Dr. Barry Sherman Institute for Medicinal Chemistry; the Yeda-Sela Center for Basic Research; the Schwartz/Reisman Collaborative Science Program; the Sam Ousher Switzer Charitable Foundation; the Dianne and Irving Kipnes Foundation, Carolyn Hewitt and Anne Christopoulos, in Memory of Sam Switzer; the Milner Foundation; and the Ben B. and Joyce E. Eisenberg Foundation.

Evolved to stop bacteria, designed for stability

New proteins, created through long-distance collaboration, might lead to the reversal of antibiotic resistance in certain bacteria

2021-03-17

(Press-News.org) Connections are crucial. Bacteria may be most dangerous when they connect - banding together to build fortress-like structures known as biofilms that afford them resistance to antibiotics. But a biomolecular scientist in Israel and a microbiologist in California have forged their own connections that could lead to new protocols for laying siege to biofilm-protected colonies. Their research was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), USA.

This interdisciplinary collaboration began with a lecture given at the Weizmann Institute of Science in the Life Sciences Colloquium. Prof. Dianne Newman of the California Institute of Technology was the speaker, and the Institute's Prof. Sarel Fleishman, of the Biomolecular Sciences Department, decided to attend, even though the lecture had no immediately apparent bearing on his own research. Newman described an enzyme she had discovered that could interrupt the metabolism of the biofilm-building bacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The enzyme interferes with the functioning of a molecule (pyocyanin) that is generated by the bacteria as they reach a high cell density and start to run out of oxygen, and it is thus responsible for helping bacteria deep within the biofilm remain viable as well as better tolerate conventional antibiotics. This molecule, however, is a double-edged sword: It can also be toxic to P. aeruginosa in the outer layers of the biofilm, where oxygen is present. Since pyocyanin impacts both biofilm development and antibiotic tolerance, Newman's lab focused on identifying ways to disrupt its activities. Newman's only problem, she said, was that the newly discovered pyocyanin-blocking enzyme was unstable and produced in minute amounts, and thus far, standard lab methods for growing such proteins had not been successful.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic bacterium that causes disease mainly in those with underlying conditions: in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients, the peripheral wounds in diabetics and on various implanted medical devices of hospital patients. Hard-to-eradicate biofilms may help infections return even after treatment, contributing to the bacteria's growing antibiotic resistance, particularly in hospital-acquired strains.

After the lecture, Fleishman suggested to Newman that they try a new approach to producing larger quantities of the enzyme. His lab specializes in computational protein design, and some of their recent work had involved redesigning vaccine proteins to make them more stable.

Rosalie Lipsh-Sokolik, a research student in his lab, together with Dr. Olga Khersonsky, a research associate, took up the challenge of designing an improved, more stable biofilm-busting enzyme. But the enzyme was unlike any Fleishman's lab had worked with before, and it would require them to develop a new methodology: It was a trimer - three identical copies of a protein bundled "like barrels strapped together," says Fleishman, and that meant that, in addition to the structure of the individual protein, they would need to understand how the entire package fit together.

The group's first step was to map the enzyme down to its atomic structure. This gave them a detailed picture of the forces that hold the protein together. When they added the resulting models of the three copies together to understand the trimer formation, they noticed that the areas of contact between copies were poorly packed, atomically speaking, and they thought these particular weak points would be a good place to start in designing a more stable structure.

But even after narrowing down the potential sites for adjustment, the number of design possibilities for such a protein complex was huge. Lipsh-Sokolik ended up adopting a combined, two-pronged approach. The first was to look for proteins made by other bacteria that are similar but slightly different, to see what could be borrowed. The second was a sort of "subtle" atomistic design approach, identifying just a dozen or so points on the enzyme that might be tweaked and trying out different modeled combinations of amino acids at just those points.

The beauty of the computer design methods developed in Fleishman's lab is not only the fact that they can produce, in a very short time, hundreds of thousands of different possible protein designs, but they also rank them from most-likely to work to not likely to work at all. Still, the only way to know if your hypothesis is correct - about the areas that need reinforcement or the ability of an enzyme to still function despite changes to its protein sequence - is to make those proteins and test them in real biological systems. Enter Dr. Chelsey M. VanDrisse, a postdoctoral fellow in the Newman lab, who led all the experimental tests of the Fleishman lab designs.

Fleishman admits his team was nervous when VanDrisse and Newman told them that they could conduct experiments on only ten of the designed trimer enzymes due to the highly challenging nature of the experiments. Their challenges were not limited to creating these new proteins, but included figuring out how to purify them in sufficient quantities in the lab and then testing them on real biofilm-building Pseudomonas aeruginosa in combination with standard antibiotic treatment. The question was, could the team not only produce a more active protein, but determine whether its application could facilitate biofilm control and begin to understand the mechanisms underpinning the enzyme`s effects?

"Both teams were over the moon when the results came in," says Fleishman: Eight of the ten designed enzymes were produced in larger-than-normal quantities in Newman's lab, without, it seemed, compromising their biofilm-fighting abilities. VanDrisse jokingly raved that she could now produce so much protein she "could have put it in my cereal every morning!" "This showed that our hypothesis about the contact areas was correct," says Fleishman. One enzyme seemed especially robust and was produced in substantial amounts, so VanDrisse and Newman went all the way: They set out to check if this version of the enzyme could, at least in the lab, work together with a commonly used clinical antibiotic to eradicate the biofilm.

In fact, they found the enzyme, in combination with this antibiotic, worked much better than they had expected. Further analysis suggested the enzyme first helps the antibiotic kill the bacteria in the oxygenated outer regions of the biofilm in a way that had not before been seen, leading, in short time, to a significant reduction in the total number of viable biofilm cells.

Fleishman adds that, as the collaboration between two groups of scientists who normally read different journals, attend different conferences and experiment with very different methods on different scales deepened -- VanDrisse even making it to the Weizmann lab just before the first COVID-19 lockdowns - he realized that what had started for him as a test of his lab's computational protein design methods now had a very real chance of leading to a cure for some of the most aggressive bacterial infections. It all came down to making the right connections.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Simple blood test could replace surgery for some brain tumour patients

2021-03-17

A research breakthrough shows that a simple blood test could reduce, or in some cases replace, the need for intrusive surgery when determining the best course of treatment for patients with a specific type of brain tumour.

Researchers at the Brain Tumour Research Centre of Excellence at the University of Plymouth have discovered a biomarker which helps to distinguish whether meningioma - the most common form of adult primary brain tumour - is grade I or grade II.

The grading is significant because lower grade tumours can sometimes remain dormant for long periods, not requiring high risk surgery or harsh treatments such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Tumours classified as grade II can progress to become cancerous and more aggressive treatment may be needed in order ...

Pressure sensors could ensure a proper helmet fit to help protect the brain

2021-03-17

Many athletes, from football players to equestrians, rely on helmets to protect their heads from impacts or falls. However, a loose or improperly fitted helmet could leave them vulnerable to traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), a leading cause of death or disability in the U.S. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Sensors have developed a highly sensitive pressure sensor cap that, when worn under a helmet, could help reveal whether the headgear is a perfect fit.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1.6 to 3.8 million sports- and recreation-related TBIs occur each year in the U.S. Field data suggest that loose or improperly fitted helmets can contribute ...

Socioeconomic factors play key role in COVID-19 impact on Blacks, Hispanics

2021-03-17

March 17, 2021-- A new study published online in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society reveals how socioeconomic factors partially explain the increased odds that Black and Hispanic Americans have of testing positive for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

In "Association of Race and Ethnicity With COVID-19 Test Positivity and Hospitalization Is Mediated by Socioeconomic Factors," Hayley B. Gershengorn, MD, associate professor, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and co-authors ...

Scientists shrink pancreatic tumors by starving their cellular 'neighbors'

2021-03-17

Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute demonstrated for the first time that blocking "cell drinking," or macropinocytosis, in the thick tissue surrounding a pancreatic tumor slowed tumor growth--providing more evidence that macropinocytosis is a driver of pancreatic cancer growth and is an important therapeutic target. The study was published in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

"Now that we know that macropinocytosis is 'revved up' in both pancreatic cancer cells and the surrounding fibrotic tissue, blocking the process might provide a 'double whammy' to pancreatic tumors," ...

New software improves accuracy of factories' mass-produced 3D-printed parts

2021-03-17

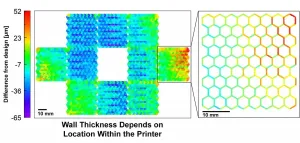

Researchers at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign developed software to improve the accuracy of 3D-printed parts, seeking to reduce costs and waste for companies using additive manufacturing to mass produce parts in factories.

"Additive manufacturing is incredibly exciting and offers tremendous benefits, but consistency and accuracy on mass-produced 3D-printed parts can be an issue. As with any production technology, parts built should be as close to identical as possible, whether it is 10 parts or 10 million," said Professor Bill King, Andersen Chair in the Department of Mechanical Science and Engineering and leader of the project.

The team's ...

More than one in 10 patients with lung cancer do not know what type they have

2021-03-17

- The increasing complexity of treatments for lung cancer and language differences can make it difficult for patients to communicate with their medical teams

- Risks of jeopardising the treatment and care journey as well as recent progress in patient empowerment.

Lugano, Switzerland; Denver, CO, USA, 17 March 2021 - More than one in 10 patients with lung cancer do not know what type of tumour they have, according to data from a 17-country study carried out by the Global Lung Cancer Coalition (GLCC) to be presented at the European Lung Cancer Conference (ELCC) ...

When volcanoes go metal

2021-03-17

What would a volcano - and its lava flows - look like on a planetary body made primarily of metal? A pilot study from North Carolina State University offers insights into ferrovolcanism that could help scientists interpret landscape features on other worlds.

Volcanoes form when magma, which consists of the partially molten solids beneath a planet's surface, erupts. On Earth, that magma is mostly molten rock, composed largely of silica. But not every planetary body is made of rock - some can be primarily icy or even metallic.

"Cryovolcanism is volcanic activity on icy worlds, and we've seen it happen on Saturn's moon Enceladus," says Arianna Soldati, assistant professor of marine, earth and atmospheric sciences at NC State and lead author of a paper describing the ...

Serious vision impairment declines among older Americans between 2008 and 2017

2021-03-17

TORONTO, ON - American adults 65 years old and older have better vision than that age group did nearly a decade ago, according to a recent study published in the journal Ophthalmic Epidemiology.

In 2008, 8.3% of those aged 65 and older in the US reported serious vision impairment. In 2017 that number decreased to 6.6% for the 65-plus cohort. Put another way: if vision impairment rates had remained at 2008 levels, an additional 848,000 older Americans would have suffered serious vision impairment in 2017.

"The implications of a reduction in vision impairment are significant," ...

Cancer mutations insight could boost detection and personalize treatments

2021-03-17

Cancer develops when changes occur with one or more genes in our cells. A change in a gene is called a fault or a mutation.

The inherited gene mutations found in this study, are passed from parent to child and are common in the population. However, each one individually does not significantly raise cancer risk.

Instead, these mutations collectively act to raise the risk of cancer developing. They do not directly cause cancer, instead they most likely interact with many other risk factors or random mutations that accumulate over a person's lifetime.

Cancers caused by inherited faulty genes were previously thought to be very rare, compared with mutations that happen by chance as we ...

Boosting insect diversity may provide more consistent crop pollination services

2021-03-17

Fields and farms with more variety of insect pollinator species provide more stable pollination services to nearby crops year on year, according to the first study of its kind.

An international team of scientists led by the University of Reading carried out the first ever study of pollinator species stability over multiple years across locations all around the world, to investigate how to reduce fluctuations in crop pollination over time.

They found areas with diverse communities of pollinators, and areas with stable populations of dominant species, suffered fewer year-to-year fluctuations ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Seabird poop could have been used to fertilize Peru's Chincha Valley by at least 1250 CE, potentially facilitating the expansion of its pre-Inca society

Resilience profiles during adversity predict psychological outcomes

AI and brain control: A new system identifies animal behavior and instantly shuts down the neurons responsible

Suicide hotline calls increase with rising nighttime temperatures

What honey bee brain chemistry tells us about human learning

Common anti-seizure drug prevents Alzheimer’s plaques from forming

Twilight fish study reveals unique hybrid eye cells

Could light-powered computers reduce AI’s energy use?

Rebuilding trust in global climate mitigation scenarios

Skeleton ‘gatekeeper’ lining brain cells could guard against Alzheimer’s

HPV cancer vaccine slows tumor growth, extends survival in preclinical model

How blood biomarkers can predict trauma patient recovery days in advance

People from low-income communities smoke more, are more addicted and are less likely to quit

No association between mRNA COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy and autism in children, new research shows

Twist-controlled magnetism grows beyond the moiré

Root microbes could help oak trees adapt to drought

Emergency department–initiated buprenorphine for opioid use disorder

Call for action on understudied lung cancer in never-smokers

Different visual experiences give rise to different neural wiring

Wearable trackers can detect depression relapse weeks before it returns, study finds

Air pollution and the progression of physical function limitations and disability in aging adults

Historically Black college or university attendance and cognition in US Black adults

New “crucial” advance for quantum computers: researchers manage to read information stored in Majorana qubits

7,000 years of change: How humans reshaped Caribbean coral reef food chains

Virus-based therapy boosts anti-cancer immune responses to brain cancer

Ancient fish ear stones reveal modern Caribbean reefs have lost their dietary complexity

American College of Lifestyle Medicine announces updated dietary position statement for treatment and prevention of chronic disease

New findings highlight two decades of evidence supporting pecans in heart-healthy diets

Case report explores potential link between mRNA COVID-19 vaccines and cancer

Healthy versions of low-carb and low-fat diets linked to better cardiovascular and metabolic health

[Press-News.org] Evolved to stop bacteria, designed for stabilityNew proteins, created through long-distance collaboration, might lead to the reversal of antibiotic resistance in certain bacteria