(Press-News.org) Our knowledge of Alzheimer's disease has grown rapidly in the past few decades but it has proven difficult to translate fundamental discoveries about the disease into new treatments. Now researchers at the California National Primate Research Center at the University of California, Davis, have developed a model of the early stages of Alzheimer's disease in rhesus macaques. The macaque model, published March 18 in the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association could allow better testing of new treatments.

The model was developed by Professor John Morrison's laboratory at the CNPRC, in collaboration with Professor Jeffrey Kordower of Rush University Medical Center and Paramita Chakrabarty, assistant professor at the University of Florida.

Alzheimer's disease is thought to be caused by misfolding of the tau and amyloid proteins. Misfolded proteins spread through the brain, leading to inflammation and cell death. Tau protein is commonly found in neurons of the brain and central nervous system, but not elsewhere.

Researchers think that decades may elapse between the silent beginnings of the disease and the first signs of cognitive decline. Understanding what happens over these years could be key to preventing or reversing symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. But it is difficult to study therapeutic strategies without a powerful animal model that resembles the human condition as closely as possible, Morrison said. Much research has focused on transgenic mice that express a human version of amyloid or tau proteins, but these studies have proven difficult to translate into new treatments.

New translational models needed

Humans and monkeys have two forms of the tau protein in their brains, but rodents only have one, said Danielle Beckman, postdoctoral researcher at the CNPRC and first author on the paper.

"We think the macaque is a better model, because it expresses the same versions of tau in the brain as humans do," she said.

Mice also lack certain areas of neocortex such as prefrontal cortex, a region of the human brain that is highly vulnerable to Alzheimer's disease. Prefrontal cortex is present in rhesus macaques and critically important for cognitive functions in both humans and monkeys. There is a critical need for new and better animal models for Alzheimer's disease that can stand between mouse models and human clinical trials, Beckman said.

Chakrabarty and colleagues created versions of the human tau gene with mutations that would cause misfolding, wrapped in a virus particle. These vectors were injected into rhesus macaques, in a brain region called the entorhinal cortex, which is highly vulnerable in Alzheimer's disease.

Within three months, they could see that misfolded tau proteins had spread to other parts of the animal's brains. They found misfolding both of the introduced human mutant tau protein and of the monkey's own tau proteins.

"The pattern of spreading demonstrated unequivocally that tau-based pathology followed the precise connections of the entorhinal cortex and that the seeding of pathological tau could pass from one region to the next through synaptic connections," Morrison said. "This capacity to spread through brain circuits results in the damage to cortical areas responsible for higher level cognition quite distant from the entorhinal cortex," he said.

The same team has previously established spreading of misfolded amyloid proteins in macaques, representing the very early stages of Alzheimer's disease, by injecting short pieces of faulty amyloid. The new tau protein model likely represents a middle stage of the disease, Beckman said.

"We think that this represents a more degenerative phase, but before widespread cell death occurs," she said.

The researchers next plan to test if behavioral changes comparable to human Alzheimer's disease develop in the rhesus macaque model. If so, it could be used to test therapies that prevent misfolding or inflammation.

"We have been working to develop these models for the last four years," Morrison said. "I don't think you could do this without a large collaborative team and the extensive resources of a National Primate Research Center."

INFORMATION:

Additional co-authors on the paper are: at the California National Primate Research Center, Sean Ott, Amanda Dao, Eric Zhou and Kristine Donis-Cox; William Janssen, Icahn School of Medicine, New York; Scott Muller, Rush University School of Medicine, Chicago. Morrison also has an appointment at the Department of Neurology, UC Davis School of Medicine.

The work was supported by the NIH through a collaboration between the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs and National Institute of Aging, and by the Alzheimer's Association.

IN BRIEF:

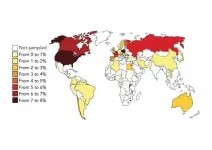

It's a first: approximately 100 scientists in 42 countries joined forces to learn about the incidence of parental burnout.

They found that Western countries are the most affected by parental burnout.

The cause? The often individualistic culture of Western countries. This international study, published in Affective Science, shows how culture, rather than socio-economic factors, plays a predominant role in parental burnout.

The individualism is more pronounced during health crises.

Does the incidence of parental burnout depend on a country's culture? This question was at the heart of the first international study on the subject for which hundreds of scientists in 42 countries mobilised. In other words, the global scientific ...

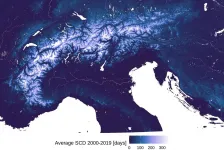

The results, published in the renowned scientific journal The Cryosphere, have made it possible to reliably describe snow trends at up to 2000 metres above sea level. Higher than that, there are too few measuring stations to be able to extract reliable information for the entire Alpine region. This consistent data set spans five decades and was created through the collaboration of more than 30 scientists from each of the Alpine states. The results and data collected represent a valuable aid for future studies, especially those which centre on climate change.

"This ...

Bottlenose dolphins learn to cope with coastal construction activities. That is the conclusion of a study published in END ...

A large gathering of fish tempts harbour porpoises to search for food around oil and gas platforms, even though the noise from these industrial plants normally to scare the whales away. Decommissioned platforms may therefore serve as artificial reefs in the North Sea.

Harbour porpoises are one of the smallest of all whales and the only whale that with certainty breeds in Danish waters. The harbour porpoise was protected in 1967 in Danish Waters, and researchers from Aarhus University, Denmark, have previously shown that underwater noise from ships, and seismic surveys of the seabed scare the porpoises away.

A brand new study now shows that in some parts of the year there are ...

A new study in Behavioral Ecology, published by Oxford University Press, finds that women are less likely to procreate in urban areas that have a higher percentage of females than males in the population.

Although the majority modern cities have more women than men and thus suffer from lower fertility rates, the effects of female-biased sex ratios - having more women than men in a population - is less studied than male-biased ratios. Researchers here analyzed how female-biased sex ratios are linked to marriages, reproductive histories, dispersal, and the effects of urbanization on society.

The research team from University of Turku, University of Helsinki and Pennsylvania ...

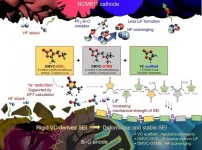

A joint research team, affiliated with UNIST has unveiled a novel electrolyte additive that could enable a long lifespan and fast chargeability of high-energy-density lithium-ion batteries (LIBs).

Published in the February 2021 issue of Nature Communications, this research has been carried out by Professor Nam-Soon Choi and Professor Sang Kyu Kwak in the School of Energy and Chemical Engineering, in collaboration with Professor Sung You Hong in the Department of Chemistry at UNIST. It has also been participated by Professor Jaephil Cho in the School of Energy and Chemical Engineering at UNIST.

As the demand for large-capacity batteries (i.e., EV batteries) increases, efforts are actively underway to replace the conventional lithium-ion ...

Researchers from the University of Helsinki's Finnish Museum of Natural History Luomus and the National Museums of Kenya have discovered four lichen species new to science in the rainforests of the Taita Hills in southeast Kenya.

Micarea pumila, M. stellaris, M. taitensis and M. versicolor are small lichens that grow on bark of trees and on decaying wood. The species were described based on morphological features and DNA-characters.

"Species that belong to the Micarea genus are known all over the world, including Finland. However, the Micarea species recently described from the Taita ...

Researchers from Arizona State University, New York University, and Northwestern University published a new paper in the Journal of Marketing that examines how marketers can fuel positive WOM without using explicit incentives.

The study, forthcoming in the Journal of Marketing, is titled "How Marketing Perks Influence Word of Mouth" and is authored by Monika Lisjak, Andrea Bonezzi, and Derek Rucker.

Word-of-mouth (WOM) is arguably the most influential means of persuasion and can be a critical driver of a company's growth. For this reason, many companies offer consumers incentives to encourage them to generate WOM. Classic examples of this practice are referral and seeding programs, whereby a company literally "pays" ...

A study from Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, has yielded new answers to fundamental questions about the relationship between the size of an atom and its other properties, such as electronegativity and energy. The results pave the way for advances in future material development. For the first time, it is now possible under certain conditions to devise exact equations for such relationships.

"Knowledge of the size of atoms and their properties is vital for explaining chemical reactivity, structure and the properties of molecules and materials of all kinds. This is fundamental research that is necessary for us to make important advances," explains Martin Rahm, the main author of the study and research leader from ...

(MARCH 17, 2021) - The current outbreak of COVID-19 has raised many questions about the value of consideration of standardized testing through the admissions process. One of the many Coronavirus cancellations included a growing number of universities to waive SAT and ACT scores as an admissions requirement for 2022 applicants.

With schools shifting their policy to making standardized "test-optional" and possibly permanently phasing out testing scores in the future as some college experts argue that standardized tests create barriers to students which could reduce their likelihood of acceptance.

A new study led by senior research scientist Paul Westrick from the College Board (ACT, Inc.), along with UTSA professor of management, ...