(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. -- Scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have developed a way to use a cell's own recycling machinery to destroy disease-causing proteins, a technology that could produce entirely new kinds of drugs.

Some cancers, for instance, are associated with abnormal proteins or an excess of normally harmless proteins. By eliminating them, researchers believe they can treat the underlying cause of disease and restore a healthy balance in cells.

The new technique builds on an earlier strategy by researchers and pharmaceutical companies to remove proteins residing inside of a cell, and expands on this system to include proteins outside or on the surface of liver cells.

"In the past, to develop a new drug, we often needed to find a molecule that bound to the protein of interest and also changed the function of the protein. But there are many potential proteins associated with diseases whose function you cannot block easily," says Weiping Tang, a professor of pharmacy and chemistry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who led the new research. "With the targeted protein degradation strategy, we can go after many of those proteins."

Tang, with colleagues in the UW-Madison School of Pharmacy, demonstrated the new method in proof-of-concept experiments on lab-grown liver cells. They were able to neutralize multiple extracellular proteins, including EGFR, a cancer-associated protein. The scientists published their findings March 4 in the journal ACS Central Science.

The technology works much like a city's trash-collection system. Antibodies attach tags for destruction to specific proteins, marking them as unwanted. A shuttle protein on the liver cell, serving as a kind of garbage truck, recognizes these markers, engulfs the protein, and ferries it to the protein-digesting compartment of the cell, which breaks down the protein into reusable parts.

Many researchers over the past several years, including the Tang group, have developed tools to selectively target for destruction certain cellular proteins found on the inside of cells, named PROTACs. Multiple PROTAC-based drugs are now in clinical trials to treat several cancers.

The Tang lab is now expanding the scope of targets to additional proteins found outside of or on the surface of the liver cell. They have turned to the lysosome, a compartment of the cell that digests and destroys all kinds of materials, including what the cell engulfs from outside. Since the liver is the primary organ that breaks down proteins in the body, it is an ideal tissue to selectively degrade undesired proteins.

To gain access to the lysosome, the researchers relied on a lysosome shuttle named ASGPR. The shuttle is primarily found on the surface of liver cells. It recognizes certain sugars on proteins and delivers the proteins to the lysosome for digestion.

To help encourage ASGPR to recognize and help destroy disease-causing proteins, researchers in earlier studies learned they could attach three specific sugars to the proteins. But first they had to figure out how to go about attaching them to the proteins they wanted to eliminate.

Tang's group focused on antibodies, which are ideal candidates since they recognize and bind to specific proteins. The team attached the sugary tag that would activate ASGPR to an antibody that would track down the specific proteins they hoped to destroy. In this way, the scientists could shuttle the protein to the lysosome of liver cells with this highly targeted trash-collection system.

They tested their technology against several proteins, including EGFR, which tumors produce in excess. By attaching the sugary tag to an EGFR antibody, the scientists were able to deplete a significant amount of the protein that otherwise accumulated outside of cancerous liver cells grown in the lab.

Tang's lab is now working to refine the ASGPR method by making it more effective, and to expand the strategy to destroy proteins on the surface of other types of cells. They are also interested in collaborating with other researchers to help them test the removal of a wider array of disease-associated proteins.

"I believe there's a great future ahead of us, but we need to invest our resources and time to investigate the protein degradation strategy further," says Tang.

INFORMATION:

--Eric Hamilton,

(608) 263-1986,

eshamilton@wisc.edu

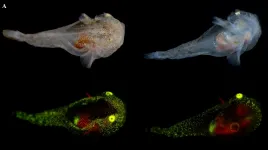

For the first time, scientists have documented biofluorescence in an Arctic fish species. The study, led by researchers at the American Museum of Natural History who spent hours in the icy waters off of Greenland where the red-and-green-glowing snailfish was found, is published today in the American Museum Novitates.

"Overall, we found marine fluorescence to be quite rare in the Arctic, in both invertebrate and vertebrate lineages," said John Sparks, a curator in the American Museum of Natural History's Department of Ichthyology and one of the authors of the ...

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic changed the higher education experience for students across the United States, with more than 90 percent of institutions reporting a shift in education delivery with the arrival of COVID-19.

The rapid transition to remote study came with its own learning curve for students and faculty alike. But for many students with disabilities, the shift offered new educational modalities as well as challenges - and the hope that some changes will continue after the threat of the virus subsides.

"This was a really unique, historical moment," says Nicholas Gelbar '06 (ED), '07 MEd, '13 Ph.D., an associate research professor with the Neag School of Education. "Remote learning, ...

Millions of children weighing less than 15kg are currently denied access to Ivermectin treatment due to insufficient safety data being available to support a change to the current label indication. The WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN)'s new meta-analysis published today provides evidence that supports removing this barrier and improving treatment equity. ...

DURHAM, N.H.-- Researchers at the University of New Hampshire have found that more than 50% of children in high-risk populations in the United States are not receiving behavioral health services that could improve their developmental outcomes when it comes to mental and physical health problems.

In their END ...

HOUSTON - (March 18, 2021) - If you're looking for one technique to maximize photon output from plasmons, stop. It takes two to wrangle.

Rice University physicists came across a phenomenon that boosts the light from a nanoscale device more than 1,000 times greater than they anticipated.

When looking at light coming from a plasmonic junction, a microscopic gap between two gold nanowires, there are conditions in which applying optical or electrical energy individually prompted only a modest amount of light emission. Applying both together, however, caused a burst of light that far exceeded ...

When it comes to recreational crabbing--one of the most iconic pastimes along Maryland's shores--the current estimate of 8% of "total male commercial harvest" runs just a little too low. Biologists, with local community support, found stronger evidence for the underestimate in the END ...

As one of the founding members of the International Rye Genome Sequencing Group (IRGSG), the University of Maryland (UMD) co-published the first full reference genome sequence for rye in Nature Genetics. UMD and international collaborators saw the need for a reference genome of this robust small grain to allow for the tracking of its useful genes and fulfill its potential for crop improvement across all major varieties of small grains, including wheat, barley, triticale (a cross between wheat and rye that is gaining popularity), and rye. Following the model of international collaboration used ...

Wheat stripe rust is one of the most important wheat diseases and is caused by the plant-pathogenic fungi Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici (Pst). Though Pst is known to be highly host-specific, it is interestingly able to infect two unrelated host plants, wheat and barberry, at different spore stages. Pst infects wheat through its urediniospores and infects barberry with its basidiospores.

"This complex life cycle poses interesting questions on the co-evolution between the pathogen and the hosts, as well the different mechanisms of pathogenesis underlying the infection of ...

The Journal of Anthropological Research has just published a new article on the development of linguistic documentation among heritage language speakers: "Articulating Lingual Life Histories and Language Ideological Assemblages: Indigenous Activists within the North Fork Mono and Village of Tewa Communities."

Specifically, it focuses on the biographical information of individual speakers, and the significance they place on the language in question. Author Paul V. Kroskrity focused his research on two specific communities - the North Fork Rancheria of Mono Indians in California and the Village of Tewa, First Mesa, Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona ...

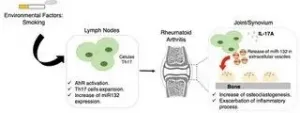

In a study aimed at investigating the mechanism responsible for exacerbating rheumatoid arthritis in smokers, researchers at the Center for Research on Inflammatory Diseases (CRID), linked to the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil, discovered a novel path in the inflammatory process associated with the bone damage caused by rheumatoid arthritis. The discovery opens up opportunities for new therapeutic interventions to mitigate the effects of the disease, for which there is no specific treatment at this time.

An article on the study is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences ...