(Press-News.org) Large areas of forests regrowing in the Amazon to help reduce carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, are being limited by climate and human activity.

The forests, which naturally regrow on land previously deforested for agriculture and now abandoned, are developing at different speeds. Researchers at the University of Bristol have found a link between slower tree-growth and land previously scorched by fire.

The findings were published today [date] in Nature Communications, and suggest a need for a better protection of these forests if they are to help mitigate the effects of climate change.

Global forests are expected to contribute a quarter of pledged mitigation under the 2015 Paris Agreement. Many countries pledged in their Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to restore and reforest millions of hectares of land to help achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. Until recently, this included Brazil, which in 2015 vowed to restore and reforest 12 million hectares, an area approximately equal to that of England.

Part of this reforestation can be achieved through the natural regrowth of secondary forests, which already occupy about 20% of deforested land in the Amazon. Understanding how the regrowth is affected by the environment and humans will improve estimates of the climate mitigation potential in the decade ahead that the United Nations has called the "Decade of Ecosystem Restoration".

Viola Heinrich, lead author and PhD student from the School of Geographical Sciences at the University of Bristol, said, "Our results show the strong effects of key climate and human factors on regrowth, stressing the need to safeguard and expand secondary forest areas if they are to have any significant role in the fight against climate change."

Annually, tropical secondary forests, which are growing on used land, can absorb carbon up to 11 times faster than old-growth forests. However, there are many driving factors that can influence the spatial patterns of regrowth rate, such as when forest land is burned either to clear for agriculture or when fire elsewhere has spread.

The research was led by researchers at the University of Bristol and Brazil's National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and included scientists from the Universities of Cardiff and Exeter, UK.

Scientists used a combination of satellite-derived images that detect changes in forest cover over time to identify secondary forest areas and their ages as well as satellite data that can monitor the aboveground carbon, environmental factors and human activity.

They found that the impact of disturbances such as fire and repeated deforestations prior to regrowth reduced the regrowth rate by 20% to 55% across different areas of the Amazon.

"The regrowth models we developed in this study will be useful for scientists, forest managers and policy makers, highlighting the regions that have the greatest regrowth potential." Said Heinrich.

The research team also calculated the contribution of Amazonian Secondary Forests to Brazil's net emissions reduction target and found that by preserving the current area, secondary forests can contribute to 6% of Brazil's net emissions reduction targets. However, this value reduces rapidly to less than 1% if only secondary forests older than 20 years are preserved.

In December 2020, Brazil amended its pledge (NDC) under the Paris Agreement such that there is now no mention of the 12 million hectares of forest restoration or eliminating illegal deforestation as was pledged in Brazil's original NDC target in 2015.

Co-author Dr Jo House, University of Bristol said "The findings in our study highlight the carbon benefits of forest regrowth and the negative impact of human action if these forests are not protected. In the run up to the 26th Conference of the Parties, this is a time when countries should be raising their climate ambitions for protecting and restoring forest ecosystems, not lowering them as Brazil seems to have done."

Co-author Dr Luiz Aragão, National Institute of Space Research in Brazil, added "Across the tropics several areas could be used to regrow forests to remove CO2 from the atmosphere. Brazil is likely to be the tropical country with the largest potential for this kind of Nature-based solution, which can generate income to landowners, reestablish ecosystems services and place the country again as a global leader in the fight against climate change."

The team will now focus their next steps on applying their methods to estimate the regrowth of secondary forest across the tropics.

INFORMATION:

OSAKA, Japan. If you were given the option to eat a delicious meal by yourself, or share that meal with your loved ones, you would need as very good excuse ready if you chose the former. Turns out, fish share a similar inclination to look after each other.

For the first time ever, a research group led by researcher Shun Satoh and Masanori Kohda, professor of the Graduate School of Science, Osaka City University, have shown these altruistic tendencies in fish through a series of prosocial choice tasks (PCT) where they gave male convict cichlid fish two choices: the antisocial option of receiving food for themselves alone and the prosocial option of receiving food for themselves and their partner.

"As a result, it can be said that the convict cichlid ...

In a recent study led by the University of Bristol, scientists have shown how to simultaneously harness multiple forms of regulation in living cells to strictly control gene expression and open new avenues for improved biotechnologies.

Engineered microbes are increasingly being used to enable the sustainable and clean production of chemicals, medicines and much more. To make this possible, bioengineers must control when specific sets of genes are turned on and off to allow for careful regulation of the biochemical processes involved.

Their findings are reported today in the journal Nature Communications.

Veronica Greco, lead author ...

Scientists have discovered in more detail than ever before how the human body's immune system reacts to malaria and sickle cell disease.

The researchers from the universities of Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Exeter and Imperial College, London have published their findings in Nature Communications.

Every year there are ~200 million cases of malaria, which causes ~400,000 deaths.

As it causes resistance against malaria, the sickle cell disease mutation has spread widely, especially in people from Africa.

But if a child inherits a double dose of the gene - from both mother and father - they will develop ...

Researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI have for the first time observed photochemical processes inside the smallest particles in the air. In doing so, they discovered that additional oxygen radicals that can be harmful to human health are formed in these aerosols under everyday conditions. They report on their results today in the journal Nature Communications.

It is well known that airborne particulate matter can pose a danger to human health. The particles, with a maximum diameter of ten micrometres, can penetrate deep into lung tissue and settle ...

Sabrina L. Spencer, PhD, is a CU Boulder researcher and a CU Cancer Center member. Spencer recently won two awards: the Damon Runyon-Rachleff Innovation Award (from the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation) and the Emerging Leader Award (from The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research). The preliminary research she used to apply for the grants, "Melanoma subpopulations that rapidly escape MAPK pathway inhibition incur DNA damage and rely on stress signalling," was published in Nature Communications on March 19, 2021. We spoke to Spencer about the awards and how she plans to use them to ...

Researchers looking at miniscule levels of plutonium pollution in our soils have made a breakthrough which could help inform future 'clean up' operations on land around nuclear power plants, saving time and money.

Publishing in the journal Nature Communications, researchers show how they have measured the previously 'unmeasurable' and taken a step forward in differentiating between local and global sources of plutonium pollution in the soil.

By identifying the isotopic 'fingerprint' of trace-level quantities of plutonium in the soil which matched the ...

A study of Japanese university students and recent graduates has revealed that writing on physical paper can lead to more brain activity when remembering the information an hour later. Researchers say that the unique, complex, spatial and tactile information associated with writing by hand on physical paper is likely what leads to improved memory.

"Actually, paper is more advanced and useful compared to electronic documents because paper contains more one-of-a-kind information for stronger memory recall," said Professor Kuniyoshi L. Sakai, a neuroscientist at the University of Tokyo and corresponding author of the research recently published in Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. The research was completed with collaborators from the NTT Data Institute of Management Consulting.

Contrary ...

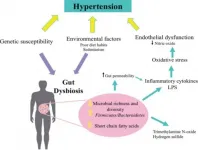

Philadelphia, March 19, 2021 - In recent years, fermented dairy foods have been gaining attention for their health benefits, and a new review published in the Journal of Dairy Science indicates these foods could help reduce conditions like hypertension (high blood pressure). A team of investigators from the Center for Food Research and Development in Sonora, Mexico, and the National Technological Institute of Mexico in Veracruz reports on numerous studies of fermented milks as antihypertensive treatments and in relation to gut microbiota modulation. They also examine the potential mechanistic pathways of gut modulation through antihypertensive fermented milks.

In addition to the impact of genetics and the environment, there is growing ...

During the first six months of the pandemic, as people attempted to stay away from hospitals caring for those sick with COVID-19, potentially avoidable hospitalizations for non-COVID-19-related conditions fell far more among white patients than Black patients, according to a new study that looked at admissions to UCLA Health hospitals.

The findings indicate that the COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated existing racial health care disparities and suggest that during the pandemic, African Americans may have had worse access than whites to outpatient care that could have helped prevent deterioration of their non-COVID-19 health conditions, said Dr. ...

LA JOLLA, CALIF. - March 19, 2021 - Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute have identified a drug candidate that blocks the uptake of glutamine, a key food source for many tumors, and slows the growth of melanoma. The drug is a small molecule that targets a glutamine transporter, SLC1A5, which pumps the nutrient into cancer cells--offering a promising new approach for treating melanoma and other cancers. The study was published in the journal Molecular Cancer Therapeutics.

"While great strides have been made recently in the treatment of melanoma, many patients' tumors become resistant to therapy, and this has become a major obstacle in the successful treatment of the disease," says Ze'ev ...