Deluge of DNA changes drives progression of fatal melanomas

2021-03-22

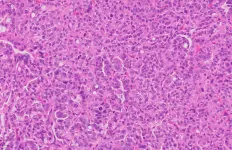

(Press-News.org) Melbourne researchers have revealed how melanoma cells are flooded with DNA changes as this skin cancer progresses from early, treatable stages through to fatal end-stage disease.

Using genomics, the team tracked DNA changes occurring in melanoma samples donated by patients as their disease progressed, right through to the time the patient died. This revealed dramatic and chaotic genetic changes that accumulated in the melanoma cells as the cancers progressed, providing clues to potential new approaches to treating this disease.

The research, published in Nature Communications, was led by Professor Mark Shackleton, Professor Director of Oncology at Alfred Health and Monash University; Professor Tony Papenfuss, who leads WEHI's Computational Biology Theme and co-heads the Computational Cancer Biology Program at Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre; and Dr Ismael Vergara, a computational biologist at WEHI, Peter Mac and the Melanoma Institute Australia.

At a glance

Genomics has been used to track DNA changes in melanoma samples donated by patients whose disease recurred and progressed after treatment.

The research revealed that end-stage melanomas acquired dramatic and chaotic genetic changes that are associated with aggressive disease growth and treatment resistance.

Understanding the genetic changes that drive melanoma growth and treatment resistance could lead to new approaches to treating this cancer.

Tracking a devastating cancer

Melanoma - the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in Australia - is caused by damaging changes occurring in the DNA of skin cells called melanocytes, usually as a result of exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight. These genetic changes enable uncontrolled growth of the cells, forming a melanoma. As the melanoma cells keep dividing, some accumulate even more DNA changes, helping them to grow even faster and spread, said Professor Shackleton.

"At early stages, melanomas can be cured with surgery. However, they sometimes recur and progress to more aggressive forms. While there are excellent new therapies in these contexts, for some patients this progressing disease is difficult to treat," he said.

"We used DNA sequencing to document genetic changes that occurred as melanomas recurred and progressed in patients."

The team obtained genome sequencing data from tumours that had been donated by these patients and fed it into a mathematical model. This revealed that, as melanomas progress, they acquire increasingly dramatic genetic changes that add substantially to the initial DNA damage from UV radiation that caused the melanoma in the first place, said Professor Papenfuss.

"Early-stage primary melanomas showed changes in their DNA from UV damage - akin to mis-spelt words in a book. These changes were enough to allow the melanoma cells to grow uncontrollably in the skin," he said.

"In contrast, end-stage, highly aggressive melanomas, in addition to maintaining most of the original DNA damage, accumulated even more dramatic genetic changes. Every patient had melanoma cells in which the total amount of DNA had doubled - a very unusual phenomenon not seen in normal cells - but on top of that, large segments of DNA were rearranged or lost - like jumbled or missing pages in a book. We think this deluge of DNA changes 'supercharged' the genes that were driving the cancer, making the disease more aggressive.

"The genomes in the late-stage melanomas were completely chaotic. We think these mutations occur in a sudden, huge wave, distinct from to the gradual DNA changes that accumulate from UV exposure in form earlier-stage melanomas. The melanoma cells that acquire these chaotic changes seem to overwhelm the earlier, less-abnormal, slower growing cells," Professor Papenfuss said.

New insights into melanoma

Professor Shackleton said the research provided an in-depth explanation of how melanomas change as they grow and may also provide clues about how melanoma could be treated.

"We mapped sequential DNA changes to track the spread of the disease in individual cases, creating 'family trees' of melanoma cells that grew, spread and changed over time in each patient. In early-stage melanomas in the skin, the DNA changes were consistent with UV-damage, while the changes we saw in later-stage melanoma were totally wild, and associated with increased growth and spread of the disease, and evasion of the body's immune defences. We could also link some DNA changes to the development of treatment resistance," he said.

The research also revealed key cancer genes that may contribute to the growth and spread of the melanoma.

"Many patients' late-stage melanomas had damage to genes known to control cell growth and to protect the structure of DNA during cell growth and division. When these genes don't work properly, cell growth becomes uncontrolled and the DNA inside cells becomes even more abnormal - it's a snowball effect. The findings also suggest that therapies which exploit these damaging changes might be useful for treating late-stage melanoma," Professor Shackleton said.

The study included tumour samples from Peter Mac's Cancer tissue Collection After Death (CASCADE) program - in which patients volunteer to undergo a rapid autopsy following their death.

"Our whole team would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the patients and their families whose participation in CASCADE made this research possible. We hope that the insights we have gained will lead to better treatments for people with melanoma," Professor Shackleton said.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the Lorenzo and Pamela Galli Charitable Trust, the Australian NHMRC, Pfizer Australia, veski, the Victorian Cancer Agency, a European Commission Horizon 2020 grant, the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, Tobin Brothers Funerals, the Peter MacCallum Cancer Foundation, Bioplatforms Australia, the Melanoma Institute of Australia, Cancer Council of Victoria, the Victorian Cancer Biobank, the Melbourne Melanoma Project and the Victorian Government.

Additional Media Contact:

Alfred Hospital media office

E L.Humphrys@alfred.org.au

T +61 438 187 529

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-22

Clinically, multiple lines of evidence show that chronic pain and depressive symptoms are frequently encountered. Patients suffered from both pain and depression are likely to become insensitive to drug treatment, indicating a refractory disease. The neural mechanism under this comorbidity remains unclear.

In a study published in Nature Neuroscience, the research team led by Prof. ZHANG Zhi and Dr. LI Juan from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), reported the discrete thalamocortical circuits underlying the pain symptom caused by tissue injury and depression-like states.

Being the gateway towards cerebral cortex and considered as the major source of 'nociceptive ...

2021-03-22

The research team led by Prof. ZHANG Jie from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences made progress on real-time determination of earthquake focal mechanism through deep learning. The work was published in Nature Communications.

Since there are connections between characteristics of the rupture surface of the source fault and seismic wave radiated by the source, it's vital to monitor the earthquake by immediate determination of the source focal mechanism which inferred from multiple ground seismic records.

However, it's hard to calculate the mechanism from the simple ...

2021-03-22

A combination of an array of atomic-level techniques has allowed researchers to show how changes in an environment-sensing protein enable bacteria to survive in different habitats, from the human gut to deep-sea hydrothermal vents.

"The study gives us unprecedented atomic-level insight into how bacteria adapt to changing conditions," says Stefan Arold, professor of bioscience at KAUST. "To obtain these insights, we pushed the limits of three different methods of investigation and combined their results into a unified picture."

The histone-like nucleoid-structuring (H-NS) protein allows bacteria to sense changes in their environment, such as changes in temperature and salinity. Previously, the team had shown how the intestinal pathogen Salmonella typhimurium ...

2021-03-22

People are not very nice to machines. The disdain goes beyond the slot machine that emptied your wallet, a dispenser that failed to deliver a Coke or a navigation system that took you on an unwanted detour.

Yet USC researchers report that people affected by COVID-19 are showing more goodwill -- to humans and to human-like autonomous machines.

"The new discovery here is that when people are distracted by something distressing, they treat machines socially like they would treat other people. We found greater faith in technology due to the pandemic and a closing of the gap between humans and machines," said Jonathan Gratch, senior author of the study and director for virtual humans research at the USC Institute for Creative Technologies.

The findings, which appeared recently ...

2021-03-22

Cancer immunotherapy may get a boost from an unexpected direction: bacteria residing within tumor cells. In a new study published in Nature, researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science and their collaborators have discovered that the immune system "sees" these bacteria and shown they can be harnessed to provoke an immune reaction against the tumor. The study may also help clarify the connection between immunotherapy and the gut microbiome, explaining the findings of previous research that the microbiome affects the success of immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy treatments of the past decade or so have dramatically improved recovery rates from certain ...

2021-03-22

National work-family policies that give lower-income families more time together while allowing them paid time off are more effective for children's psychological health than cash transfers, according to a study of developed nations led by Baylor University.

In a study of about 200,000 children in 20 developed nations, the United States ranked lowest in overall policies aimed at helping parents support children.

The study, published in the journal Social Forces, supports the view of critics who say that the United States government does not do enough to mandate ...

2021-03-22

Repeatedly getting angry, hitting, shaking or yelling at children is linked with smaller brain structures in adolescence, according to a new study published in Development and Psychology. It was conducted by Sabrina Suffren, PhD, at Université de Montréal and the CHU Sainte?Justine Research Centre in partnership with researchers from Stanford University.

The harsh parenting practices covered by the study are common and even considered socially acceptable by most people in Canada and around the world.

"The implications go beyond changes in the brain. I think what's ...

2021-03-22

Cancers are not only made of tumor cells. In fact, as they grow, they develop an entire cellular ecosystem within and around them. This "tumor microenvironment" is made up of multiple cell types, including cells of the immune system, like T lymphocytes and neutrophils.

The tumor microenvironment has predictably drawn a lot of interest from cancer researchers, who are constantly searching for potential therapeutic targets. When it comes to the immune cells, most research focuses on T lymphocytes, which have become primary targets of cancer immunotherapy ...

2021-03-22

Wikipedia page views could be used to monitor global awareness of biodiversity, proposes a research team from UCL, ZSL, and the RSPB.

Using their new metric, the research team found that awareness of biodiversity is marginally increasing, but the rate of change varies greatly between different groups of animals, as they report in a paper included in an upcoming special section of Conversation Biology.

Lead author, PhD student Joe Millard (UCL Centre for Biodiversity & Environment Research, UCL Biosciences and Institute of Zoology, ZSL) said: "As extinctions and biodiversity losses ramp up worldwide, largely due to climate change and other human actions, it's vital that ...

2021-03-22

A study by the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund shows that gorilla families come together to support young gorillas that lose their mothers.

The findings, published in the journal eLife, use the Fossey Fund's more than 50-year dataset to discover how maternal loss influences young gorillas' social relationships, survival and future reproduction. The study shows when young mountain gorillas lose their mothers, the rest of the group helps buffer the loss by strengthening their relationships with the orphans.

"Mothers are incredibly important for survival early in life--this is something that is shared across all mammals," said lead author Dr. Robin Morrison. "But in social mammals, like ourselves, mothers often continue to provide vital support up to adulthood and even beyond."

"In ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Deluge of DNA changes drives progression of fatal melanomas