(Press-News.org) Call it the evolutionary march of the penguins.

More than 50 million years ago, the lovable tuxedoed birds began leaving their avian relatives at the shoreline by waddling to the water's edge and taking a dive in the pursuit of seafood.

Webbed feet, flipper-like wings and unique feathers all helped penguins adapt to their underwater excursions. But new research from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln has shown that the evolution of diving is also in their blood, which optimized its capture and release of oxygen to ensure that penguins wouldn't waste their breath while holding it.

Relative to land-dwelling birds, penguin blood is known to contain more hemoglobin: the protein that picks up oxygen from the lungs and transports it through the bloodstream before dropping it off at various tissues. That abundance could partly explain the underwater proficiency of, say, the emperor penguin, which dives deeper than any bird and has been documented holding its breath for more than 30 minutes while preying on krill, fish and squid.

Still, the particulars of their hemoglobin -- and how much it actually evolved to help penguins become fish-gobbling torpedoes that spend up to half of their lives underwater -- remained open questions. So Nebraska biologists Jay Storz and Anthony Signore, who often study the hemoglobin of birds that survive miles above sea level, decided to investigate the birds most adept at diving beneath it.

"There just wasn't a lot of comparative work on blood-oxygen transport as it relates to diving physiology in penguins and their non-diving relatives," said Signore, a postdoctoral researcher in Storz's lab.

Answering those questions meant sketching in the genetic blueprints of two ancient hemoglobins. One belonged to the common ancestor of all penguin species, which began branching from that ancestor about 20 million years ago. The other, dating back roughly 60 million years, resided in the common ancestor of penguins and their closest non-diving relatives -- albatrosses, shearwaters and other flying seabirds. The thinking was simple: Because one hemoglobin originated before the emergence of diving in the lineage, and the other after, any major differences between the two would implicate them as important to the evolution of diving in penguins.

Actually comparing the two was less simple. To start, the researchers literally resurrected both proteins by relying on models that factored in the gene sequences of modern hemoglobins to estimate the sequences of their two ancient counterparts. Signore spliced those resulting sequences into E. coli bacteria, which churned out the two ancient proteins. The researchers then ran experiments to evaluate the performance of each.

They found that the hemoglobin from the common ancestor of penguins captured oxygen more readily than did the version present in the blood of the older, non-diving ancestor. That stronger affinity for oxygen would mean less chance of leaving behind traces in the lungs, an especially vital issue among semi-aquatic birds needing to make the most of a single breath while hunting or traveling underwater.

Unfortunately, the very strength of that affinity can present difficulties when hemoglobin arrives at tissues starved for the oxygen it's carrying.

"Having a greater hemoglobin-oxygen affinity sort of acts like a stronger magnet to pull more oxygen from the lungs," Signore said. "It's great in that context. But then you're at a loss when it's time to let go."

Any breath-holding benefits gained by picking up extra oxygen, in other words, can be undone if the hemoglobin struggles to relax its iron-clad grip and release its prized cargo. The probability that it will is dictated in part by acidity and carbon dioxide in the blood. Higher levels of either make hemoglobins more likely to loosen up.

As Storz and Signore expected, the hemoglobin of the recent penguin ancestor was more sensitive to its surrounding pH, with its biochemical grip on oxygen loosening more in response to elevated acidity. And that, Signore said, made the hemoglobin more biochemically attuned to the exertion and oxygen needs of the tissues it served.

"It really is a beautiful system, because tissues that are working hard are becoming acidic," he said. "They need more oxygen, and hemoglobin's oxygen affinity is able to shift in response to that acidity to provide more oxygen.

"If pH drops by, say, 0.2 units, the oxygen affinity of penguin hemoglobin is going to decrease by more than would the hemoglobin of their non-diving relatives."

Together, the findings indicate that as penguins took to the seas, their hemoglobin evolved to maximize both the pick-up and drop-off of available oxygen -- especially when it was last inhaled five, or 10, or even 20 minutes earlier. They also illustrate the value of resurrecting proteins that last existed 20, or 40, or even 60 million years ago.

"These results demonstrate how the experimental analysis of ancestral proteins can reveal the mechanisms of biochemical adaptation," Storz said, "and also shed light on how organismal physiology evolved in response to new environmental challenges."

INFORMATION:

The team detailed its findings in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Storz and Signore authored the study with Nebraska's Hideaki Moriyama, associate professor of biological sciences; Michael Tift of the University of North Carolina Wilmington; Federico Hoffmann of Mississippi State University; and Todd Schmitt of SeaWorld San Diego.

The researchers received support from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

LA JOLLA, CA--An analysis of thousands of genomes from people with and without the rare eye disease known as MacTel has turned up more than a dozen gene variants that are likely causing the condition to develop and worsen for a significant share of patients.

The discovery, by a team of scientists from Scripps Research and the Lowy Medical Research Institute, in collaboration with Columbia University in New York and UC San Diego, provides a new avenue to pursue for diagnosis and treatment. It also sheds light on fundamental aspects of metabolism in the retina, a tissue with one of the highest energy demands in the human body. Findings appear today in the journal Nature Metabolism.

"It's exciting to uncover new answers to the ...

The cost of the rechargeable lithium-ion batteries used for phones, laptops, and cars has fallen dramatically over the last three decades, and has been a major driver of the rapid growth of those technologies. But attempting to quantify that cost decline has produced ambiguous and conflicting results that have hampered attempts to project the technology's future or devise useful policies and research priorities.

Now, MIT researchers have carried out an exhaustive analysis of the studies that have looked at the decline in the prices these batteries, which are the dominant rechargeable ...

Stuttgart - A team of scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems (MPI-IS) in Germany, from Seoul National University in Korea and from the Harvard University in the US, successfully developed a predictive model and closed-loop controller of a soft robotic fish, designed to actively adjust its undulation amplitude to changing flow conditions and other external disturbances. Their work "Modeling and Control of a Soft Robotic Fish with Integrated Soft Sensing" was published in Wiley's Advanced Intelligent Systems journal, in a special issue on "Energy Storage and Delivery in Robotic Systems".

Each ...

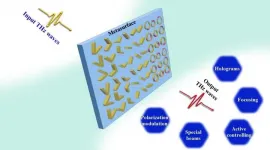

THz waves have a plethora of applications ranging from biomedical and medical examinations, imaging, environment monitoring, to wireless communications, because of the abundant spectral information, low photon energy, strong penetrability, and shorter wavelength. THz waves with technological advances not only determined by the high-efficiency sources and detectors but also decided by a variety of the high-quality THz components/functional devices. However, traditional THz devices should be thick enough to realize the desired wave-manipulating functions, hindering the development of THz integrated systems and applications. Although metamaterials have been ...

Tailoring light is much like tailoring cloth, cutting and snipping to turn a bland fabric into one with some desired pattern. In the case of light, the tailoring is usually done in the spatial degrees of freedom, such as its amplitude and phase (the "pattern" of light), and its polarization, while the cutting and snipping might be control with spatial light modulators and the like. This burgeoning field is known as structured light, and is pushing the limits in what we can do with light, enabling us to see smaller, focus tighter, image with wider fields of view, probe with fewer photons, and to pack information ...

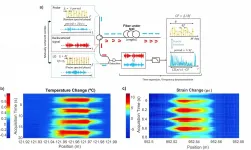

Distributed optical fiber sensing (DOFS) is currently a mature technology that allows "transforming" a conventional fiber optic into a continuous array of individual sensors, which are distributed along its length. Between the panoply of techniques developed in the field of DOFS, those based on phase-sensitive optical time-domain reflectometry (ΦOTDR) have gained a great deal of attention, mainly due to their ability to measure strain and temperature perturbations in real time. These unique features, along with other advantages of distributed sensors (reduced weight, electromagnetic immunity ...

Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) are changing the lighting and display industry and have obtained significant advances than traditional lighting sources. The traditional materials LEDs, e.g., III-V semiconductor LEDs, organic LEDs (OLEDs) and quantum-dot LEDs (QLEDs), have achieved great success and gradually realized commercialization, but still face some challenges. The OLEDs have the low carrier transport capability and exciton recombination, which would hinder the improvement of brightness. Besides, QLEDs show challenges for the tedious manufacturing process and the reliance on hydrophobic insulating long ligands also hinders their stability and electrical conductivity.

Compared with these traditional materials, quasi-2D ...

A large proportion of dementia deaths in England and Wales may be due to socioeconomic deprivation, according to new research led by Queen Mary University of London.

The team also found that socioeconomic deprivation was associated with younger age at death with dementia, and poorer access to accurate diagnosis.

Dementia is the leading cause of death in England and Wales, even during the COVID pandemic, and is the only disease in the top ten causes of death without effective treatment.

The research, published in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, examines Office for National Statistics mortality data for England and Wales, and finds that in 2017, 14,837 excess dementia deaths were attributable to deprivation, equating to 21.5 per cent of all dementia deaths ...

Uncovering detailed travel patterns and habitat use of sharks along and across shelf territories has been historically challenging - especially for most pelagic shark species - which remain offshore for most of their lives. Their vertical diving behavior has been a subject of inquiry for a long time, and for young sharks in particular, has remained elusive.

Using cutting-edge 3D satellite technology, a study led by Florida Atlantic University's Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, in collaboration with NOAA's National Marine Fisheries Service; OCEARCH; The South Fork Natural History Museum and Nature Center; and the Wildlife Conservation Society, is ...

Of the many perplexing questions surrounding SARS CoV-2, a mysterious new pathogen that has killed an estimated 2.6 million people worldwide, perhaps the most insistent is this: why does the illness seem to strike in such a haphazard way, sometimes sparing the 100 year old grandmother, while killing healthy young men and women in the prime of life?

A new study by Karen Anderson, Abhishek Singharoy and their colleagues at the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, may offer some tentative clues. Their research explores MHC-I, a critical protein component of the human adaptive immune system.

The research suggests that certain variant ...