Cephalopods: Older than was thought?

Fossil find from Canada could rewrite the evolutionary history of invertebrate organisms

2021-03-23

(Press-News.org) The possibly oldest cephalopods in the earth's history stem from the Avalon Peninsula in Newfoundland (Canada). They were discovered by earth scientists from Heidelberg University. The 522 million-year-old fossils could turn out to be the first known form of these highly evolved invertebrate organisms, whose living descendants today include species such as the cuttlefish, octopus and nautilus. In that case, the find would indicate that the cephalopods evolved about 30 million years earlier than has been assumed.

"If they should actually be cephalopods, we would have to backdate the origin of cephalopods into the early Cambrian period," says Dr Anne Hildenbrand from the Institute of Earth Sciences. Together with Dr Gregor Austermann, she headed the research projects carried out in cooperation with the Bavarian Natural History Collections. "That would mean that cephalopods emerged at the very beginning of the evolution of multicellular organisms during the Cambrian explosion."

The chalky shells of the fossils found on the eastern Avalon Peninsula are shaped like a longish cone and subdivided into individual chambers. These are connected by a tube called the siphuncle. The cephalopods were thus the first organisms able to move actively up and down in the water and thus settle in the open ocean as their habitat. The fossils are distant relatives of the spiral-shaped nautilus, but clearly differ in shape from early finds and the still existing representatives of that class.

"This find is extraordinary," says Dr Austermann. "In scientific circles it was long suspected that the evolution of these highly developed organisms had begun much earlier than hitherto assumed. But there was a lack of fossil evidence to back up this theory." According to the Heidelberg scientists, the fossils from the Avalon Peninsula might supply this evidence, as on the one hand, they resemble other known early cephalopods but, on the other, differ so much from them that they might conceivably form a link leading to the early Cambrian.

The former and little explored micro-continent of Avalonia, which - besides the east coast of Newfoundland - comprises parts of Europe, is particularly suited to paleontological research, since many different creatures from the Cambrian period are still preserved in its rocks. The researchers hope that other, better preserved finds will confirm the classification of their discoveries as early cephalopods.

The research results about the 522 million-year-old fossils were published in the Nature-journal "Communications Biology". Logistic support was given by the province of Newfoundland and the Manuels River Natural Heritage Society located there. The publication in open-access format was enabled in the context of Project DEAL.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-23

Russian scientists have proposed a new algorithm for automatic decoding and interpreting the decoder weights, which can be used both in brain-computer interfaces and in fundamental research. The results of the study were published in the Journal of Neural Engineering.

Brain-computer interfaces are needed to create robotic prostheses and neuroimplants, rehabilitation simulators, and devices that can be controlled by the power of thought. These devices help people who have suffered a stroke or physical injury to move (in the case of a robotic chair or prostheses), communicate, use a computer, and operate household appliances. In addition, in combination with machine learning methods, neural interfaces ...

2021-03-23

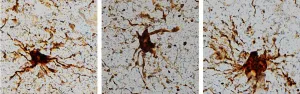

In the hours after we die, certain cells in the human brain are still active. Some cells even increase their activity and grow to gargantuan proportions, according to new research from the University of Illinois Chicago.

In a newly published study in the journal Scientific Reports, the UIC researchers analyzed gene expression in fresh brain tissue -- which was collected during routine brain surgery -- at multiple times after removal to simulate the post-mortem interval and death. They found that gene expression in some cells actually increased after death.

These 'zombie genes' -- those that increased expression after the post-mortem interval -- were specific to one type of cell: inflammatory cells called ...

2021-03-23

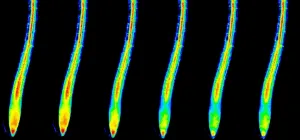

Potassium is an essential nutrient for all living things. Plants need it in large quantities, especially for growth and in order to withstand stress better. For this reason, they absorb large quantities of potassium from the soil. In agriculture, this leads to a lack of available potassium in the soil - which is why the mineral is an important component in fertilizers. A team of German and Chinese researchers has now shown, for the first time, where and how plants detect potassium deficiency in their roots, and which signalling pathways coordinate the adaptation of root growth and potassium absorption ...

2021-03-23

A number of studies have shown that human coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2 which causes COVID-19, appear to attack neurons and the nervous system in vulnerable populations. This neuroinvasion through the nasal cavity leads to the risk of neurological disorders in affected individuals. Research conducted at the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS) has identified ways to prevent the spread of infection within the central nervous system (CNS). The study, led by Professor Pierre Talbot and his research associate Marc Desforges, now at CHU-Sainte-Justine, ...

2021-03-23

According to a recent Finnish study, accumulating more brisk and vigorous physical activity can curb adiposity-induced low-grade inflammation. The study also reported that diet quality had no independent association with low-grade inflammation. The findings, based on the ongoing Physical Activity and Nutrition in Children (PANIC) Study conducted at the University of Eastern Finland, were published in the European Journal of Sport Science.

The study was made in collaboration among researchers from the University of Jyväskylä, the University of Eastern Finland, the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, and the University of Cambridge.

Low-grade inflammation is linked to many chronic diseases, but exercise can ...

2021-03-23

Casual sex is on the decline for both young men and women, according to a Rutgers University-New Brunswick study that found less alcohol consumption among both genders is a major reason while playing video games and living at home with parents are another--but only for men.

The study, published in the journal Socius, found that between 2007 and 2017, the percentage of 18-to 23-year-old men who had casual sex in the past month dropped from 38 percent to 24 percent. The percentage dropped from 31 percent to 22 percent for young women of the same age.

The most important factor driving the decline among young men is the decrease in drinking, which alone explains more than ...

2021-03-23

The vast reservoir of carbon that is stored in soils probably is more sensitive to destabilization from climate change than has previously been assumed, according to a new study by researchers at WHOI and other institutions.

The study found that the biospheric carbon turnover within river basins is vulnerable to future temperature and precipitation perturbations from a changing climate.

Although many earlier, and fairly localized, studies have hinted at soil organic carbon sensitivity to climate change, the new research sampled 36 rivers from around the ...

2021-03-23

As the pandemic's economic effects drive more people to enroll in Medicaid as safety-net health insurance, a new study suggests that the program's dental coverage can improve their oral health in ways that help them seek a new job or do better at the one they have.

The study focuses on the impact of dental coverage offered through Michigan's Medicaid expansion, called the Healthy Michigan Plan. The researchers, from the University of Michigan, used a survey and interviews to assess the impact of this coverage on the health and lives of low-income people who enrolled.

In all, 60% of the 4,090 enrollees surveyed for the new study had visited a dentist at least once since enrolling ...

2021-03-23

Daily national surveys by Carnegie Mellon University show that while COVID-19 vaccine uptake has increased, the proportion of vaccine-hesitant adults has remained unchanged. The concerns about a side effect remain high, especially among females, Black adults and those with an eligible health condition.

The Delphi Research Group at CMU in partnership with Facebook released its latest survey findings. The analyses show that vaccine hesitancy persists and point to potential tactics to combat it.

"Prior research by the CDC has found that Black and Hispanic adults are the least likely to receive the annual flu vaccine each year," said Alex Reinhart, assistant teaching professor in CMU's Department of Statistics & Data Science and a member of the Delphi ...

2021-03-23

It can be hard to resist lapsing into an exaggerated, singsong tone when you talk to a cute baby. And that's with good reason. Babies will pay more attention to baby talk than regular speech, regardless of which languages they're used to hearing, according to a study by UCLA's Language Acquisition Lab and 16 other labs around the globe.

The study found that babies who were exposed to two languages had a greater interest in infant-directed speech -- that is, an adult speaking baby talk -- than adult-directed speech. Research has already shown that monolingual babies prefer baby talk.

Some parents worry that teaching two languages could mean an infant won't learn to speak on time, but the new study shows bilingual babies are developmentally right ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Cephalopods: Older than was thought?

Fossil find from Canada could rewrite the evolutionary history of invertebrate organisms