(Press-News.org) The largest flightless bird ever to live weighed in up to 600kg and had a whopping head about half a metre long - but its brain was squeezed for space.

Dromornis stirtoni, the largest of the 'mihirungs' (an Aboriginal word for 'giant bird'), stood up to 3m high and had a cranium wider and higher than it was long due to a powerful big beak, leading Australian palaeontologists to look inside its brain space to see how it worked.

The new study, just published in the journal Diversity, examined the brains of the extinct giant mihirungs or dromornithid birds that were a distinctive part of the Australian fauna for many millions of years, before going extinct around 50,000 years ago.

"Together with their large, forward-facing eyes and very large bills, the shape of their brains and nerves suggested these birds likely had well-developed stereoscopic vision, or depth perception, and fed on a diet of soft leaves and fruit," says lead author Flinders University researcher Dr Warren Handley.

"The shape of their brains and nerves have told us a lot about their sensory capabilities, and something about their possible lifestyle which enabled these remarkable birds to live in the forests around river channels and lakes across Australia for an extremely long time.

"It's exciting when we can apply modern imaging methods to reveal features of dromornithid morphology that were previously completely unknown," Dr Handley says.

The new research, based on fossil remains ranging from about 24 million years ago to the last in the line (Dromornis stirtoni), indicates mihirung brains and nerves are most like those of modern day chickens and Australian mallee fowl.

"The unlikely truth is these birds were related to fowl - chickens and ducks - but their closest cousin and much of their biology still remains a mystery," says vertebrate palaeontologist and senior author Associate Professor Trevor Worthy.

"While the brains of dromornithids were very different to any bird living today, it also appears they shared a similar reliance on good vision for survival with living ratities such as ostrich and emu."

The researchers compared the brain structures of four mihirungs - from the earliest Dromornis murrayi at about 24 million years ago (Ma) to Dromornis planei and Ilbandornis woodburnei from 12 Ma and Dromornis stirtoni, at 7 Ma.

Ranging from cassowary in size to what's known as the world's largest bird, Flinders vertebrate palaeontologist Associate Professor Worthy says the largest and last species Dromornis stirtoni was an "extreme evolutionary experiment".

"This bird had the largest skull but behind the massive bill was a weird cranium. To accommodate the muscles to wield this massive bill, the cranium had become taller and wider than it was long, and so the brain within was squeezed and flattened to fit.

"It would appear these giant birds were probably what evolution produced when it gave chickens free reign in Australian environmental conditions and so they became very different to their relatives the megapodes - or chicken-like landfowls which still exist in the Australasian region," Associate Professor Worthy says.

The large, flightless birds Dromornithidae - also called demon ducks of doom or thunder birds - existed from the Oligocene to Pleistocene Epochs.

During prehistory, the body sizes of eight species of dromornithids became larger and smaller depending climate and available feed.

The Flinders researchers used the skulls of fossil birds to extract endocasts of the brains to describe how these related to modern birds such as megapodes and waterfowl. Brain models were also made from CT scans of five other dromornithid skulls from fossil sites in Queensland and the Northern Territory. The oldest 25 Ma Dromornis murrayi specimen was found in the famed Riversleigh World Heritage Area in Queensland.

INFORMATION:

The paper, 'Endocranial Anatomy of the Giant Extinct Australian Mihirung Birds (Aves, Dromornithidae)' by WD Handley and TH Worthy has been published in Diversity, 13(3), 124; DOI: 10.3390/d13030124.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, people have grown accustomed to wearing facemasks, but many coverings are fragile and not easily disinfected. Metal foams are durable, and their small pores and large surface areas suggest they could effectively filter out microbes. Now, researchers reporting in ACS' Nano Letters have transformed copper nanowires into metal foams that could be used in facemasks and air filtration systems. The foams filter efficiently, decontaminate easily for reuse and are recyclable.

When a person with a respiratory infection, such ...

Nature produces a startling array of patterned materials, from the sensitive ridges on a person's fingertip to a cheetah's camouflaging spots. Although nature's patterns arise spontaneously during development, creating patterns on synthetic materials is more laborious. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Central Science have found an easy way to make patterned materials having complex microstructures with variations in mechanical, thermal and optical properties -- without the need for masks, molds or printers.

In animals, patterns form before birth ...

Honeybees play a scent-driven game of telephone to guide members of a colony back to their queen, according to a new study led by University of Colorado Boulder. The research, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, highlights how insects with limited cognitive abilities can achieve complex feats when they work together--even creating what looks like a miniature and buzzing version of a telecommunications network.

The findings also serve as a testament to a honeybee's love for its queen. These matriarchs are the most important members of any hive: They're the only females able ...

Given the finite nature of fossil fuel reserves and the devastating environmental impacts of relying on fossil fuels, the development of clean energy sources is among the most pressing challenges facing modern industrial civilization. Solar energy is an attractive clean energy option, but the widescale implementation of solar energy technologies will depend on the development of efficient ways of converting light energy into chemical energy.

Like many other research groups, the members of Professor Takehisa Dewa's research team at Nagoya Institute of Technology in Japan have turned to biological photosynthetic apparatuses, which ...

[Background]

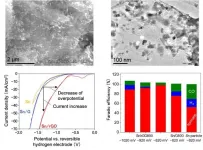

Decreasing the emission and efficient utilization (fixation) of carbon dioxide (CO2) are worldwide issues to prevent global warming. Promotion of the use of renewable energy is effective in reducing CO2 emissions. However, since there are large time-dependent fluctuations and large regional differences in renewable energy production, it is necessary to establish a fixation technology to allow efficient energy transportation and storage. Thus, there is increasing interest in technologies for synthesizing useful chemicals from CO2 using electricity derived from renewable energy. ...

A new study suggests that Sargramostim, a medication often used to boost white blood cells after cancer treatments, is also effective in treating and improving memory in people with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. This medication comprises of a natural human protein produced by recombinant DNA technology (yeast-derived rhu GM-CSF/Leukine®).

The study, from the University of Colorado Alzheimer's and Cognition Center at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus (CU Anschutz), presents evidence from their clinical trial that shows that Sargramostim may ...

(Boston)--Being persistently lonely during midlife (ages 45-64) appears to make people more likely to develop dementia and Alzheimer's Disease (AD) later in life. However, people who recover from loneliness, appear to be less likely to suffer from dementia, compared to people who have never felt lonely.

Loneliness is a subjective feeling resulting from a perceived discrepancy between desired and actual social relationships. Although loneliness does not itself have the status of a clinical disease, it is associated with a range of negative health outcomes, including sleep disturbances, depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment, and stroke. Still, feeling lonely may happen to anyone at some point in life, ...

A new study shows that if the population were fixed at current levels, the risk of population displacement due to river floods would rise by ~50% for each degree of global warming. However, if population increases are taken into account, the relative global flood displacement risk is significantly higher.

The research, by an international team from Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands, used a global climate-, hydrology- and inundation-modelling chain, including multiple alternative climate and hydrological models, to quantify the effect of global warming on displacement ...

Extremely hot and dry conditions that currently put parts of the UK in the most severe danger of wildfires once a century could happen every other year in a few decades' time due to climate change, new research has revealed.

A study, led by the University of Reading, predicting how the danger of wildfires will increase in future showed that parts of eastern and southern England may be at the very highest danger level on nearly four days per year on average by 2080 with high emissions, compared to once every 50-100 years currently.

Wildfires need a source of ignition which ...

Deforestation, certain types of reforestation and commercial palm plantations correlate with increasing outbreaks of infectious disease, shows a new study in Frontiers in Veterinary Science. This study offers a first global look at how changes in forest cover potentially contribute to vector-borne diseases--such as those carried by mosquitos and ticks--as well as zoonotic diseases, like Covid-19, which jumped from an animal species into humans. The expansion of palm oil plantations in particular corresponded to significant rises in vector-borne ...