(Press-News.org) When we grow crystals, atoms first group together into small clusters - a process called nucleation. But understanding exactly how such atomic ordering emerges from the chaos of randomly moving atoms has long eluded scientists.

Classical nucleation theory suggests that crystals form one atom at a time, steadily increasing the level of order. Modern studies have also observed a two-step nucleation process, where a temporary, high-energy structure forms first, which then changes into a stable crystal. But according to an international research team co-led by the Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), the real story is even more complicated.

Their findings, recently reported in the journal Science, reveal that rather than grouping together one-by-one or making a single irreversible transition, gold atoms will instead self-organize, fall apart, regroup, and then reorganize many times before establishing a stable, ordered crystal. Using an advanced electron microscope, the researchers witnessed this rapid, reversible nucleation process for the first time. Their work provides tangible insights into the early stages of many growth processes such as thin-film deposition and nanoparticle formation.

"As scientists seek to control matter at smaller length scales to produce new materials and devices, this study helps us understand exactly how some crystals form," said Peter Ercius, one of the study's lead authors and a staff scientist at Berkeley Lab's Molecular Foundry.

In line with scientists' conventional understanding, once the crystals in the study reached a certain size, they no longer returned to the disordered, unstable state. Won Chul Lee, one of the professors guiding the project, describes it this way: if we imagine each atom as a Lego brick, then instead of building a house one brick at a time, it turns out that the bricks repeatedly fit together and break apart again until they are finally strong enough to stay together. Once the foundation is set, however, more bricks can be added without disrupting the overall structure.

The unstable structures were only visible because of the speed of newly developed detectors on the TEAM I, one of the world's most powerful electron microscopes. A team of in-house experts guided the experiments at the National Center for Electron Microscopy in Berkeley Lab's Molecular Foundry. Using the TEAM I microscope, researchers captured real-time, atomic-resolution images at speeds up to 625 frames per second, which is exceptionally fast for electron microcopy and about 100 times faster than previous studies. The researchers observed individual gold atoms as they formed into crystals, broke apart into individual atoms, and then reformed again and again into different crystal configurations before finally stabilizing.

"Slower observations would miss this very fast, reversible process and just see a blur instead of the transitions, which explains why this nucleation behavior has never been seen before," said Ercius.

The reason behind this reversible phenomenon is that crystal formation is an exothermic process - that is, it releases energy. In fact, the very energy released when atoms attach to the tiny nuclei can raise the local "temperature" and melt the crystal. In this way, the initial crystal formation process works against itself, fluctuating between order and disorder many times before building a nucleus that is stable enough to withstand the heat. The research team validated this interpretation of their experimental observations by performing calculations of binding reactions between a hypothetical gold atom and a nanocrystal.

Now, scientists are developing even faster detectors which could be used to image the process at higher speeds. This could help them understand if there are more features of nucleation hidden in the atomic chaos. The team is also hoping to spot similar transitions in different atomic systems to determine whether this discovery reflects a general process of nucleation.

One of the study's lead authors, Jungwon Park, summarized the work: "From a scientific point of view, we discovered a new principle of crystal nucleation process, and we proved it experimentally."

INFORMATION:

The research collaboration was led by Berkeley Lab in collaboration with South Korea's Hanyang University, Seoul National University, and Institute for Basic Science.

The Molecular Foundry is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

This work was mainly supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea. Work at the Molecular Foundry was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. Additional funding was provided by the Institute for Basic Science (Korea), Samsung Science and Technology Foundation, and the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab's facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- A 10-week muscle-building and dietary program involving 50 middle-aged adults found no evidence that eating a high-protein diet increased strength or muscle mass more than consuming a moderate amount of protein while training. The intervention involved a standard strength-training protocol with sessions three times per week. None of the participants had previous weightlifting experience.

Published in the American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology and Metabolism, the study is one of the most comprehensive investigations of the health effects of diet and resistance training in middle-aged adults, the researchers say. Participants were 40-64 years ...

Fossil fuel producers in the U.S. are directly benefiting from implicit subsidies on the order of $62 billion a year because of inefficient pricing that doesn't properly account for the costs of damages to the environment, climate, and human health.

That's the finding of a newly published study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) by Yale School of the Environment Economics Professor Matthew Kotchen that analyzed gasoline, natural gas, diesel, and coal.

The total annual implicit subsidy is equivalent to an average of 3% of the U.S. gross domestic product, according to the study which examined data from 2010-2018. ...

A recent Oregon State University study found that when people feel they have resolved an argument, the emotional response associated with that disagreement is significantly reduced and, in some situations, almost entirely erased.

That reduction in stress may have a major impact on overall health, researchers say.

"Everyone experiences stress in their daily lives. You aren't going to stop stressful things from happening. But the extent to which you can tie them off, bring them to an end and resolve them is definitely going to pay dividends in terms of your well-being," said Robert Stawski, senior author on the study and an associate professor ...

The Gerontological Society of America's highly cited, peer-reviewed journals are continuing to publish scientific articles on COVID-19. The following were published between January 8 and March 15; all are free to access:

Comment on: "Beyond chronological age: Frailty and multimorbidity predict in-hospital mortality in patients with coronavirus disease 2019": Letter to the editor in The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences by Noémie Girard, MS, Geoffrey Odille, MS, Stéphane Sanchez, MD, Sarah Lelarge, ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Long before Tyrone, Jermaine and Darnell came along, there were Isaac, Abe and Prince.

A new study reveals the earliest evidence of distinctively Black first names in the United States, finding them arising in the early 1700s and then becoming increasingly common in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

The results confirm previous work that shows the use of Black names didn't start during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, as some scholars have argued, said Trevon Logan, co-author of the study and professor of economics at The Ohio State University.

"Even ...

The Amazon rainforest is teeming with creatures unknown to science--and that's just in broad daylight. After dark, the forest is a whole new place, alive with nocturnal animals that have remained even more elusive to scientists than their day-shift counterparts. In a new paper in Zootaxa, researchers described two new species of screech owls that live in the Amazon and Atlantic forests, both of which are already critically endangered.

"Screech owls are considered a well-understood group compared to some other types of organisms in these areas," says John Bates, curator of birds at the Field Museum in Chicago and one of the study's authors. "But when you start listening to them and comparing ...

Scientists estimate that dark matter and dark energy together are some 95% of the gravitational material in the universe while the remaining 5% is baryonic matter, which is the "normal" matter composing stars, planets, and living beings. However for decades almost one half of this matter has not been found either. Now, using a new technique, a team in which the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC) has participated, has shown that this "missing" baryonic matter is found filling the space between the galaxies as hot, low density gas. The same technique also gives a new tool that shows that the gravitational attraction experienced by ...

Researchers from Queen Mary University of London have developed a machine learning algorithm that ranks drugs based on their efficacy in reducing cancer cell growth. The approach may have the potential to advance personalised therapies in the future by allowing oncologists to select the best drugs to treat individual cancer patients.

The method, named Drug Ranking Using Machine Learning (DRUML), was published today in Nature Communications and is based on machine learning analysis of data derived from the study of proteins expressed in cancer cells. Having been trained on ...

The interiors of nonflowering trees such as pine and ginkgo contain sapwood lined with straw-like conduits known as xylem, which draw water up through a tree's trunk and branches. Xylem conduits are interconnected via thin membranes that act as natural sieves, filtering out bubbles from water and sap.

MIT engineers have been investigating sapwood's natural filtering ability, and have previously fabricated simple filters from peeled cross-sections of sapwood branches, demonstrating that the low-tech design effectively filters bacteria.

Now, the same team has advanced the technology and shown that it works in real-world situations. They have fabricated new xylem filters that can filter out pathogens ...

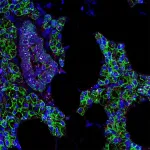

An international team of scientists has found evidence that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, infects cells in the mouth. While it's well known that the upper airways and lungs are primary sites of SARS-CoV-2 infection, there are clues the virus can infect cells in other parts of the body, such as the digestive system, blood vessels, kidneys and, as this new study shows, the mouth. The potential of the virus to infect multiple areas of the body might help explain the wide-ranging symptoms experienced by COVID-19 patients, including oral symptoms such as taste loss, ...