Researchers at Stanford and Carnegie Mellon reveal cost of key climate solution

2021-03-25

(Press-News.org) Perhaps the best hope for slowing climate change - capturing and storing carbon dioxide emissions underground - has remained elusive due in part to uncertainty about its economic feasibility.

In an effort to provide clarity on this point, researchers at Stanford University and Carnegie Mellon University have estimated the energy demands involved with a critical stage of the process. (Watch video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ZPIwwQs9aM)

Their findings, published April 8 in Environmental Science & Technology, suggest that managing and disposing of high salinity brines - a by-product of efficient underground carbon sequestration - will impose significant energy and emissions penalties. Their work quantifies these penalties for different management scenarios and provides a framework for making the approach more energy efficient.

"Designing massive new infrastructure systems for geological carbon storage with an appreciation for how they intersect with other engineering challenges--in this case the difficulty of managing high salinity brines--will be critical to maximizing the carbon benefits and reducing the system costs," said study senior author Meagan Mauter, an associate professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Stanford University.

Getting to a clean, renewable energy future won't happen overnight. One of the bridges on that path will involve dealing with carbon dioxide emissions - the dominant greenhouse gas warming the Earth - as fossil fuel use winds down. That's where carbon sequestration comes in. While most climate scientists agree on the need for such an approach, there has been little clarity about the full lifecycle costs of carbon storage infrastructure.

Salty challenge

An important aspect of that analysis is understanding how we will manage brines, highly concentrated salt water that is extracted from underground reservoirs to increase carbon dioxide storage capacity and minimize earthquake risk. Saline reservoirs are the most likely storage places for captured carbon dioxide because they are large and ubiquitous, but the extracted brines have an average salt concentration that is nearly three times higher than seawater.

These brines will either need to be disposed of via deep well injection or desalinated for beneficial reuse. Pumping it underground - an approach that has been used for oil and gas industry wastewater - has been linked to increased earthquake frequency and has led to significant public backlash. But desalinating the brines is significantly more costly and energy intensive due, in part, to the efficiency limits of thermal desalination technologies. It's an essential, complex step with a potentially huge price tag.

The big picture

The new study is the first to comprehensively assess the energy penalties and carbon dioxide emissions involved with brine management as a function of various carbon transport, reservoir management and brine treatment scenarios in the U.S. The researchers focused on brine treatment associated with storing carbon from coal-fired power plants because they are the country's largest sources of carbon dioxide, the most cost-effective targets for carbon capture and their locations are generally representative of the location of carbon dioxide point sources.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the study found higher energy penalties for brine management scenarios that prioritize treatment for reuse. In fact, brine management will impose the largest post-capture and compression energy penalty on a per-tone of carbon dioxide basis, up to an order of magnitude greater than carbon transport, according to the study.

"There is no free lunch," said study lead author Timothy Bartholomew, a former civil and environmental engineering graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University who now works for KeyLogic Systems, a contractor for the Department of Energy's National Energy Technology Laboratory. "Even engineered solutions to carbon storage will impose energy penalties and result in some carbon emissions. As a result, we need to design these systems as efficiently as possible to maximize their carbon reduction benefits."

The road forward

Solutions may be at hand.

The energy penalty of brine management can be reduced by prioritizing storage in low salinity reservoirs, minimizing the brine extraction ratio and limiting the extent of brine recovery, according to the researchers. They warn, however, that these approaches bring their own tradeoffs for transportation costs, energy penalties, reservoir storage capacity and safe rates of carbon dioxide injection into underground reservoirs. Evaluating the tradeoffs will be critical to maximizing carbon dioxide emission mitigation, minimizing financial costs and limiting environmental externalities.

"There are water-related implications for most deep decarbonization pathways," said Mauter, who is also a fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. "The key is understanding these constraints in sufficient detail to design around them or develop engineering solutions that mitigate their impact."

INFORMATION:

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.

Funding for this research provided by the National Science Foundation, the ARCS Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-25

Smoking cigarettes causes 480,000 premature deaths each year in the United States, due mainly to a two-fold risk of cardiovascular disease and a 20-fold risk of lung cancer. Although smoking rates have declined dramatically, there are currently 35 million smokers in the U.S.

In a commentary published in the Ochsner Medical Journal, Charles H. Hennekens, M.D., Dr.PH, senior author, the First Sir Richard Doll Professor, and senior academic advisor in the Schmidt College of Medicine at Florida Atlantic University, and colleagues, highlight how failure to institute smoking cessation in hospitalized patients is a missed opportunity to avoid many premature deaths.

Each year in the U.S., ...

2021-03-25

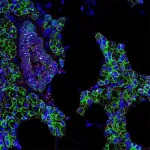

An international team led by scientists at the National Institutes of Health and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has found evidence that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, infects cells in the mouth.

While it's well known that the upper airways and lungs are primary sites of SARS-CoV-2 infection, there are clues the virus can infect cells in other parts of the body, such as the digestive system, blood vessels, kidneys and, as this new study shows, the mouth. The potential of the virus to infect multiple areas of the body might help explain the wide-ranging symptoms experienced by COVID-19 patients, including oral symptoms such as taste loss, dry mouth and blistering.

Moreover, the findings ...

2021-03-25

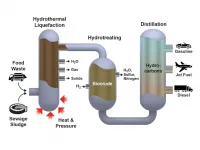

RICHLAND, WASH.--A large-scale demonstration converting biocrude to renewable diesel fuel has passed a significant test, operating for more than 2,000 hours continuously without losing effectiveness. Scientists and engineers led by the U.S. Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory conducted the research to show that the process is robust enough to handle many kinds of raw material without failing.

"The biocrude oil came from many different sources, including wastewater sludge from Detroit, and food waste collected from prison and an army base," said John Holladay, a PNNL scientist and co-director of the joint Bioproducts Institute, a collaboration between ...

2021-03-25

LA JOLLA--(March 25, 2021) The brush of an insect's wing is enough to trigger a Venus flytrap to snap shut, but the biology of how these plants sense and respond to touch is still poorly understood, especially at the molecular level. Now, a new study by Salk and Scripps Research scientists identifies what appears to be a key protein involved in touch sensitivity for flytraps and other carnivorous plants.

The findings, published March 16, 2021, in the journal eLife, help explain a critical process that has long puzzled botanists. This could help scientists better understand how plants of all kinds sense and respond to mechanical stimulation, and could also have a potential application in medical therapies that mechanically stimulate human cells such as neurons.

"We know that plants ...

2021-03-25

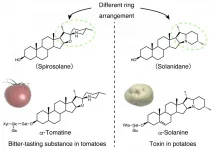

A multi-institutional collaboration has revealed that α-solanine, a toxic compound found in potato plants, is a divergent of the bitter-tasting α-tomatine, which is found in tomato plants. The research group included Associate Professor MIZUTANI Masaharu and Researcher AKIYAMA Ryota et al. of Kobe University's Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Assistant Professor WATANABE Bunta of Kyoto University's Institute for Chemical Research, Senior Research Scientist UMEMOTO Naoyuki of the RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science, and Professor MURANAKA Toshiya of Osaka University's Graduate School of Engineering.

It ...

2021-03-25

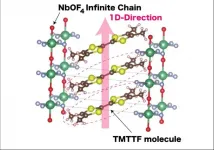

Salts are far more complicated than the food seasoning - they can even act as electrical conductors, shuttling current through systems. Extremely well studied and understood, the electrical properties of salts were first theorized in 1834. Now, nearly 200 years later, researchers based in Japan have uncovered a new kind of salt.

The results were published on March 17 in Inorganic Chemistry, a journal of the American Chemical Society.

The researchers were specifically investigating how one-dimensional versions of three-dimensional substances exhibit unique physical phenomena and functionality in a process called the ...

2021-03-25

CORVALLIS, Ore. - A novel analysis of encounters between albatross and commercial fishing vessels across the North Pacific Ocean is giving researchers important new understanding about seabird-vessel interactions that could help reduce harmful encounters.

The new research method, which combines location data from GPS-tagged albatross and commercial fishing vessels, allows researchers to accurately identify bird-vessel encounters and better understand bird behavior, environmental conditions and the characteristics that influence these encounters.

"It is hard to conceptualize how often birds ...

2021-03-25

For the first time, researchers from the SponGES project collected year-round video footage and hydrodynamic data from the mysterious world of a deep-sea sponge ground in the Arctic. Deep-sea sponge grounds are often compared to the rich ecosystems of coral reefs and form true oases. In a world where all light has disappeared and without obvious food sources, they provide a habitat for other invertebrates and a refuge for fish in the otherwise barren landscape. It is still puzzling how these biodiversity hotspots survive in this extreme environment as deep as 1500 metres below the water surface. With over 700 hundred ...

2021-03-25

Ikoma, Japan - Gear trains have been used for centuries to translate changes in gear rotational speed into changes in rotational force. Cars, drills, and basically anything that has spinning parts use them. Molecular-scale gears are a much more recent invention that could use light or a chemical stimulus to initiate gear rotation. Researchers at Nara Institute of Science and Technology (NAIST), Japan, in partnership with research teams at University Paul Sabatier, France, report in a new study published in Chemical Science a means to visualize snapshots of an ultrasmall ...

2021-03-25

People who are physically active on a regular basis recover better after surgery for colorectal cancer. However, starting to exercise only after the diagnosis is a fact had no effect on recovery, a University of Gothenburg thesis shows.

In working on his thesis, Aron Onerup, who obtained his doctorate in surgery at the University's Sahlgrenska Academy and is now a specialist doctor at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, carried out an observational study of 115 patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer.

The participants who had been physically inactive proved, three weeks after their surgery, to be at higher risk of not feeling that they ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Researchers at Stanford and Carnegie Mellon reveal cost of key climate solution