(Press-News.org) "Staph" bacteria feed on blood. They need the iron that's hidden away inside red blood cells to grow and cause infections. It turns out that these microbial vampires prefer the taste of human blood, Vanderbilt University scientists have discovered.

The researchers report in the Dec. 16 issue of Cell Host & Microbe that Staphylococcus aureus (staph) favors human hemoglobin – the oxygen-carrying protein that contains iron – over hemoglobin from other animals. The findings help explain why staph preferentially infects people and suggest that genetic variations in hemoglobin may make some individuals more susceptible to staph infections.

Staph lives in the noses of about 30 percent of all people – usually without making them ill, said Eric Skaar, Ph.D., M.P.H., associate professor of Microbiology and Immunology.

"A big question in staph biology is: why do some people continuously get infected, or suffer very serious staph infections, while other people do not? Variations in hemoglobin could contribute," he said.

If that is the case – something Skaar and his team plan to explore – it might be possible to identify patients who are more susceptible to a staph infection and provide them with prophylactic therapy in advance of a hospital stay or surgery.

Staph is a significant threat to global public health. It is the leading cause of pus-forming skin and soft tissue infections, the leading cause of infectious heart disease, the No. 1 hospital-acquired infection, and one of four leading causes of food-borne illness. Antibiotic-resistant strains of S. aureus – such as MRSA – are on the rise in hospitals and communities.

"It seems as if complete and total antibiotic resistance of the organism is inevitable at this point," Skaar said.

This dire outlook motivates Skaar and his colleagues in their search for new antibiotic targets. The group has focused on staph's nutritional requirements, searching for ways to "starve" the bug of the metals (such as iron) that it needs.

Staph obtains iron by popping open red blood cells, binding to the hemoglobin, and extracting iron from it. Skaar and colleagues previously identified the staph receptor for hemoglobin, a protein called IsdB.

In the current studies, they showed that S. aureus bacteria bind human hemoglobin preferentially over other animal hemoglobins, and that this binding occurs through the IsdB receptor. The preferential recognition of human hemoglobin by S. aureus is due to the increased affinity of IsdB for human hemoglobin compared to other animal hemoglobins.

The team studied staph's ability to infect a mouse expressing human hemoglobin (a "humanized" mouse model) and found that these mice were more susceptible to a systemic staph infection than control mice.

The investigators also examined the hemoglobin-binding preferences of other microbes and found that bacterial pathogens that exclusively infect humans, such as the bacteria that cause diphtheria, prefer human hemoglobin compared to other animal hemoglobins. In contrast, pathogens such as Pseudomonas and Bacillus anthracis (the cause of anthrax), which infect a number of different animals, "didn't exhibit a hemoglobin preference," Skaar said.

The human hemoglobin-expressing mice will be a valuable research tool, Skaar said, because staph infects these mice in a way that more closely mimics the infectious process in humans. His team will also explore whether these mice provide a good model for studying the infectious biology of other pathogens.

Skaar hopes to utilize Vanderbilt's DNA Databank, BioVU, to examine whether genetic variations in hemoglobin contribute to individual susceptibility to staph infections. His team will continue to study the molecular interaction between hemoglobin and the IsdB receptor, with the aim of disrupting this interaction with new antibiotic therapeutics.

INFORMATION:

Graduate student Gleb Pishchany is the first author of the Cell Host & Microbe paper. Other Vanderbilt authors include Amanda McCoy, Victor Torres, Ph.D., Jens Krause, M.D., and James Crowe Jr., M.D. The studies were supported by the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Blood-sucking superbug prefers taste of humans

Staphylococcus aureus bacteria bind best to human hemoglobin

2010-12-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Stanford study identifies multitude of genetic regions key to embryonic stem cell development

2010-12-16

STANFORD, Calif. — More than 2,000 genetic regions involved in early human development have been identified by researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine. The regions, called enhancers, are responsible for triggering the expression of distant genes when embryonic stem cells begin to divide to form the many tissues of a growing embryo.

"This is going to be an enormous resource for researchers interested in tracking cells involved in early human development," said Joanna Wysocka, PhD, assistant professor of developmental biology and of chemical and systems ...

Feast, famine and the genetics of obesity: You can't have it both ways

2010-12-16

LA JOLLA, CA-In addition to fast food, desk jobs, and inertia, there is one more thing to blame for unwanted pounds-our genome, which has apparently not caught up with the fact that we no longer live in the Stone Age.

That is one conclusion drawn by researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, who recently showed that mice lacking a gene regulating energy balance are protected from weight gain, even on a high fat diet. These findings have implications for the worldwide obesity epidemic and its consequences, such as type two diabetes.

In the December 16, ...

Software improves understanding of mobility problems

2010-12-16

The software tool presents data visually and this allows those without specialist training – both professionals and older people – to better understand and contribute to discussions about the mechanics of movement, known as biomechanics, when carrying out everyday activities.

The software takes motion capture data and muscle strength measurements from older people undertaking everyday activities. The software then generates a 3D animated human stick figure on which the biomechanical demands of the activities are represented visually at the joints. These demands, or stresses, ...

Insight offers new angle of attack on variety of brain tumors

2010-12-16

A newly published insight into the biology of many kinds of less-aggressive but still lethal brain tumors, or gliomas, opens up a wide array of possibilities for new therapies, according to scientists at Brown University and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). In paper published online Dec. 15 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, they describe how a genetic mutation leads to an abnormal metabolic process in the tumors that could be targeted by drug makers.

"What this tells you is that there are some forms of tumors with a fundamentally altered ...

Novel therapy for metastatic kidney cancer developed at VCU Massey Cancer Center

2010-12-16

Richmond, Va. (Dec. 15, 2010) – Researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center and the VCU Institute of Molecular Medicine (VIMM) have developed a novel virus-based gene therapy for renal cell carcinoma that has been shown to kill cancer cells not only at the primary tumor site but also in distant tumors not directly infected by the virus. Renal cell carcinoma is the most common form of kidney cancer in adults and currently there is no effective treatment for the disease once it has spread outside of the kidney.

The study, published in the journal ...

Close proximity leads to better science

2010-12-16

Absence makes your heart grow fonder, but close-quarters may boost your career.

According to new research by scientists at Harvard Medical School, the physical proximity of researchers, especially between the first and last author on published papers, strongly correlates with the impact of their work.

"Despite all of the profound advances in information technology, such as video conferencing, we found that physical proximity still matters for research productivity and impact," says Isaac Kohane, the Lawrence J. Henderson Professor of Pediatrics at Children's Hospital ...

Study links increased BPA exposure to reduced egg quality in women

2010-12-16

A small-scale University of California, San Francisco-led study has identified the first evidence in humans that exposure to bisphenol A (BPA) may compromise the quality of a woman's eggs retrieved for in vitro fertilization (IVF). As blood levels of BPA in the women studied doubled, the percentage of eggs that fertilized normally declined by 50 percent, according to the research team.

The chemical BPA, which makes plastic hard and clear, has been used in many consumer products such as reusable water bottles. It also is found in epoxy resins, which form a protective ...

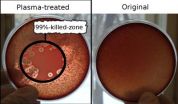

Plasma therapy: An alternative to antibiotics?

2010-12-16

Cold plasma jets could be a safe, effective alternative to antibiotics to treat multi-drug resistant infections, says a study published this week in the January issue of the Journal of Medical Microbiology.

The team of Russian and German researchers showed that a ten-minute treatment with low-temperature plasma was not only able to kill drug-resistant bacteria causing wound infections in rats but also increased the rate of wound healing. The findings suggest that cold plasmas might be a promising method to treat chronic wound infections where other approaches fail.

The ...

MDMA: Empathogen or love potion?

2010-12-16

15 December 2010, MDMA or 'ecstasy' increases feelings of empathy and social connection. These 'empathogenic' effects suggest that MDMA might be useful to enhance the psychotherapy of people who struggle to feel connected to others, as may occur in association with autism, schizophrenia, or antisocial personality disorder.

However, these effects have been difficult to measure objectively, and there has been limited research in humans. Now, University of Chicago researchers, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, are reporting their new findings in healthy volunteers ...

Sticking to dietary recommendations would save 33,000 lives a year in the UK

2010-12-16

If everyone in the UK ate their "five a day," and cut their dietary salt and unhealthy fat intake to recommended levels, 33,000 deaths could be prevented or delayed every year, reveals research published online in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.

Eating five portions of fruit and vegetables a day accounts for almost half of these saved lives, the study shows. Recommended salt and fat intakes would need to be drastically reduced to achieve similar health benefits, say the authors.

The researchers base their findings on national data for the years 2005 ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

U.S. medical care is improving, but cost and health differ depending on disease

AI challenges lithography and provides solutions

Can AI make society less selfish?

UC Irvine researchers expose critical security vulnerability in autonomous drones

Changes in smoking status and their associations with risk of Parkinson’s, death

[Press-News.org] Blood-sucking superbug prefers taste of humansStaphylococcus aureus bacteria bind best to human hemoglobin