(Press-News.org) HOUSTON - (March 25, 2021) - One of nature's most prolific cannibals could be hiding in your pantry, and biologists have used it to show how social structure affects the evolution of selfish behavior.

Researchers revealed that less selfish behavior evolved under living conditions that forced individuals to interact more frequently with siblings. While the finding was verified with insect experiments, Rice University biologist Volker Rudolf said the evolutionary principal could be applied to study any species, including humans.

In a study published online this week in Ecology Letters, Rudolf, longtime collaborator Mike Boots of the University of California, Berkeley, and colleagues showed they could drive the evolution of cannibalism in Indian meal moth caterpillars with simple changes to their habitats.

Also known as weevil moths and pantry moths, Indian meal moths are common pantry pests that lay eggs in cereals, flour and other packaged foods. As larvae, they're vegetarian caterpillars with one exception: They sometimes eat one another, including their own broodmates.

In laboratory tests, researchers showed they could predictably increase or decrease rates of cannibalism in Indian meal moths by decreasing how far individuals could roam from one another, and thus increasing the likelihood of "local" interactions between sibling larvae. In habitats where caterpillars were forced to interact more often with siblings, less selfish behavior evolved within 10 generations.

Rudolf, a professor of biosciences at Rice, said increased local interactions stack the deck against the evolution of selfish behaviors like cannibalism.

To understand why, he suggests imagining behaviors can be sorted from least to most selfish.

"At one end of the continuum are altruistic behaviors, where an individual may be giving up its chance to survive or reproduce to increase reproduction of others," he said. "Cannibalism is at the other extreme. An individual increases its own survival and reproduction by literally consuming its own kind."

Rudolf said the study provided a rare experimental test of a key concept in evolutionary theory: As local interactions increase, so does selective pressure against selfish behaviors. That's the essence of a 2010 theoretical prediction by Rudolf and Boots, the corresponding author of the meal moth study, and Rudolf said the study's findings upheld the prediction.

"Families that were highly cannibalistic just didn't do as well in that system," he said. "Families that were less cannibalistic had much less mortality and produced more offspring."

In the meal moth experiments, Rudolf said it was fairly easy to ensure that meal moth behavior was influenced by local interactions.

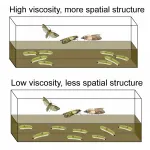

"They live in their food," he said. "So we varied how sticky it was."

Fifteen adult females were placed in several enclosures to lay eggs. The moths lay eggs in food, and larval caterpillars eat and live inside the food until they pupate. Food was plentiful in all enclosures, but it varied in stickiness.

"Because they're laying eggs in clusters, they're more likely to stay in these little family groups in the stickier foods that limit how fast they can move," Rudolf said. "It forced more local interactions, which, in our system, meant more interactions with siblings. That's really what we think was driving this change in cannibalism."

Rudolf said the same evolutionary principal might also be applied to the study of human behavior.

"In societies or cultures that live in big family groups among close relatives, for example, you might expect to see less selfish behavior, on average, than in societies or cultures where people are more isolated from their families and more likely to be surrounded by strangers because they have to move often for jobs or other reasons," he said.

Rudolf has studied the ecological and evolutionary impacts of cannibalism for nearly 20 years. He finds it fascinating, partly because it was misunderstood and understudied for decades. Generations of biologists had such a strong aversion to human cannibalism that they wrote off the behavior in all species as a "freak of nature," he said.

That finally began to change slowly a few decades ago, and cannibalism has now been documented in well over 1,000 species and is believed to occur in many more.

"It's everywhere. Most animals that eat other animals are cannibalistic to some extent, and even those that don't normally eat other animals -- like the Indian meal moth -- are often cannibalistic," Rudolf said. "There's no morality attached to it. That's just a human perspective. In nature, cannibalism is just getting another meal."

But cannibalism "has important ecological consequences," Rudolf said. "It determines dynamics of populations and communities, species coexistence and even entire ecosystems. It's definitely understudied for its importance."

He said the experimental follow-up to his and Boots' 2010 theory paper came about almost by chance. Rudolf saw an epidemiological study Boots published a few years later and realized the same experimental setup could be used to test their prediction.

While the moth study showed that "limiting dispersal," and thus increasing local interactions, can push against the evolution of cannibalism by increasing the cost of extreme selfishness, Rudolf said the evolutionary push can probably go the other way as well. "If food conditions are poor, cannibalism provides additional benefits, which could push for more selfish behavior."

He said it's also possible that a third factor, kin recognition, could also provide an evolutionary push.

"If you're really good at recognizing kin, that limits the cost of cannibalism," he said. "If you recognize kin and avoid eating them, you can afford to be a lot more cannibalistic in a mixed population, which can have evolutionary benefits."

Rudolf said he plans to explore the three-way interaction between cannibalism, dispersal and kin recognition in future studies.

"It would be nice to get a better understanding of the driving forces and be able to explain more of the variation that we see," he said. "Like, why are some species extremely cannibalistic? And even within the same species, why are some populations far more cannibalistic than others. I don't think it's going to be one single answer. But are there some basic principles that we can work out and test? Is it super-specific to every system, or are there more general rules?"

Additional co-authors include Dylan Childs and Jessica Crossmore of the University of Sheffield, and Hannah Tidbury of both the University of Sheffield and the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science in Weymouth, England.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation (1256860, 0841686, 2011109) the National Institutes of Health (R01GM122061) and the Natural Environment Research Council (NEJ0097841).

Does selfishness evolve? Ask a cannibal

Study confirms evolutionary link between social structure and selfishness

2021-03-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Global evidence for how EdTech can support pupils with disabilities is 'thinly spread'

2021-03-25

An 'astonishing' deficit of data about how the global boom in educational technology could help pupils with disabilities in low and middle-income countries has been highlighted in a new report.

Despite widespread optimism that educational technology, or 'EdTech', can help to level the playing field for young people with disabilities, the study found a significant shortage of evidence about which innovations are best-positioned to help which children, and why; specifically in low-income contexts.

The review also found that many teachers lack training on how to use new technology, or are reluctant to do so.

The ...

Should you take fish oil? Depends on your genotype

2021-03-25

Fish oil supplements are a billion-dollar industry built on a foundation of purported, but not proven, health benefits. Now, new research from a team led by a University of Georgia scientist indicates that taking fish oil only provides health benefits if you have the right genetic makeup.

The study, led by Kaixiong Ye and published in PLOS Genetics, focused on fish oil (and the omega-3 fatty acids it contains) and its effect on triglycerides, a type of fat in the blood and a biomarker for cardiovascular disease.

"We've known for a few decades that a higher level of omega-3 fatty acids in the blood is associated with a lower risk of heart disease," said Ye, assistant professor ...

Common Alzheimer's treatment linked to slower cognitive decline

2021-03-25

Cholinesterase inhibitors are a group of drugs recommended for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease, but their effects on cognition have been debated and few studies have investigated their long-term effects. A new study involving researchers from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden and published in the journal Neurology shows persisting cognitive benefits and reduced mortality for up to five years after diagnosis.

Alzheimer's disease is a cognitive brain disease that affects millions of patients around the world. Some 100,000 people in Sweden live with the diagnosis, which has a profound impact on the lives of both them and their families. Most of those who receive a diagnosis are over 65, but there are some patients ...

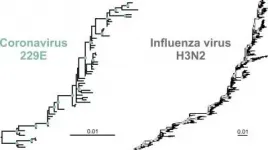

Will COVID-19 vaccines need to be adapted regularly?

2021-03-25

Influenza vaccines need to be evaluated every year to ensure they remain effective against new influenza viruses. Will the same apply to COVID-19 vaccines? In order to gauge whether and to what extent this may be necessary, a team of researchers from Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin compared the evolution of endemic 'common cold' coronaviruses with that of influenza viruses. The researchers predict that, while the pandemic is ongoing, vaccines will need to undergo regular updates. A few years into the post-pandemic period, however, vaccines ...

Women accumulate Alzheimer's-related protein faster

2021-03-25

Alzheimer's disease seems to progress faster in women than in men. The protein tau accumulates at a higher rate in women, according to research from Lund University in Sweden. The study was recently published in Brain.

Over 30 million people suffer from Alzheimer's disease worldwide, making it the most common form of dementia. Tau and beta-amyloid are two proteins known to aggregate and accumulate in the brain in patients with Alzheimer's.

The first protein to aggregate in Alzheimer's is beta-amyloid. Men and women are equally affected by the first disease stages, and the analysis did not show any differences in the accumulation of ...

Massive study reveals few differences between men and women's brains

2021-03-25

How different are men and women's brains? The question has been explored for decades, but a new study led by Rosalind Franklin University neuroscientist END ...

Combination therapy protects against advanced Marburg virus disease

2021-03-25

GALVESTON, Texas - A new study conducted at the Galveston National Laboratory at the The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB) has shown substantial benefit to combining monoclonal antibodies and the antiviral remdesivir against advanced Marburg virus. The study was published today in Nature Communications.

"Marburg is a highly virulent disease in the same family as the virus that causes Ebola. In Africa, patients often arrive to a physician very ill. It was important to test whether a combination of therapies would work better with really sick people, said Tom Geisbert, a professor in the Department of Microbiology & Immunology at UTMB and the principal investigator ...

In certain circumstances, outsourcing poses risks to vendors

2021-03-25

TROY, N.Y. -- Outsourcing routine tasks, like payroll, customer service, and accounting, offers well-known benefits to businesses and contributes to an economy in which entrepreneurial vendors can support industry and expand employment. However, new research from the Lally School of Management at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute discovered that not all client-vendor relationships are beneficial for the vendors.

"It's important to observe and study both sides of a business relationship," said T. Ravichandran, a chaired professor of information systems in Lally and an author of a new study published in Information Systems Frontiers. "For businesses to thrive, they need a vibrant vendor community that will support ...

Ocean's mammals at crucial crossroads

2021-03-25

The ocean's mammals are at a crucial crossroads - with some at risk of extinction and others showing signs of recovery, researchers say.

In a detailed review of the status of the world's 126 marine mammal species - which include whales, dolphins, seals, sea lions, manatees, dugongs, sea otters and polar bears - scientists found that accidental capture by fisheries (bycatch), climate change and pollution are among the key drivers of decline.

A quarter of these species are now classified as being at risk of extinction (vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered on the IUCN Red List), with the near-extinct vaquita porpoise and the critically endangered North Atlantic ...

Researchers capture first 3D super-resolution images in living mice

2021-03-25

WASHINGTON -- Researchers have developed a new microscopy technique that can acquire 3D super-resolution images of subcellular structures from about 100 microns deep inside biological tissue, including the brain. By giving scientists a deeper view into the brain, the method could help reveal subtle changes that occur in neurons over time, during learning, or as result of disease.

The new approach is an extension of stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy, a breakthrough technique that achieves nanoscale resolution by overcoming the traditional diffraction limit of optical microscopes. Stefan Hell won the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing this super-resolution imaging technique.

In Optica, The ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Does a past abortion or miscarriage affect a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer?

Could a treatment redirect the body’s anti-viral immune response to target cancer cells?

How does universal, free prescription drug coverage affect older adults’ finances and behaviors?

Do certain factors affect life expectancy in people with spina bifida?

New study: Routine aspirin therapy prevents severe preeclampsia in at-risk populations

Afraid of chemistry at school? It’s not all the subject’s fault

How tech-dependency and pandemic isolation have created ‘anxious generation’

Nearly three quarters of US baby foods are ultra-processed, new study finds

Nonablative radiofrequency may improve sexual function in postmenopausal women

Pulsed dynamic water electrolysis: Mass transfer enhancement, microenvironment regulation, and hydrogen production optimization

Coordination thermodynamic control of magnetic domain configuration evolution toward low‑frequency electromagnetic attenuation

High‑density 1D ionic wire arrays for osmotic energy conversion

DAYU3D: A modern code for HTGR thermal-hydraulic design and accident analysis

Accelerating development of new energy system with “substance-energy network” as foundation

Recombinant lipidated receptor-binding domain for mucosal vaccine

Rising CO₂ and warming jointly limit phosphorus availability in rice soils

Shandong Agricultural University researchers redefine green revolution genes to boost wheat yield potential

Phylogenomics Insights: Worldwide phylogeny and integrative taxonomy of Clematis

Noise pollution is affecting birds' reproduction, stress levels and more. The good news is we can fix it.

Researchers identify cleaner ways to burn biomass using new environmental impact metric

Avian malaria widespread across Hawaiʻi bird communities, new UH study finds

New study improves accuracy in tracking ammonia pollution sources

Scientists turn agricultural waste into powerful material that removes excess nutrients from water

Tracking whether California’s criminal courts deliver racial justice

Aerobic exercise may be most effective for relieving depression/anxiety symptoms

School restrictive smartphone policies may save a small amount of money by reducing staff costs

UCLA report reveals a significant global palliative care gap among children

The psychology of self-driving cars: Why the technology doesn’t suit human brains

Scientists discover new DNA-binding proteins from extreme environments that could improve disease diagnosis

Rapid response launched to tackle new yellow rust strains threatening UK wheat

[Press-News.org] Does selfishness evolve? Ask a cannibalStudy confirms evolutionary link between social structure and selfishness