Circadian clock gene Rev-erb linked to dawn phenomenon in type 2 diabetes

2021-03-25

(Press-News.org) Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine, Shandong University in China and other institutions may have found an explanation for dawn phenomenon, an abnormal increase of blood sugar only in the morning, observed in many patients with type 2 diabetes. They report in the journal Nature that mice lacking the circadian clock gene called Rev-erb in the brain show characteristics similar to those of dawn phenomenon.

The researchers then looked at Rev-erb gene expression in patients with type 2 diabetes comparing a group with dawn phenomenon to a group without it and found that the gene's expression followed a different temporal pattern between these two groups. The findings support the idea that an altered daily rhythm of expression of the Rev-erb gene may underlie dawn phenomenon. Future investigations may lead to therapies.

"We began this study to investigate what was the function of Rev-erb in the brain," said co-corresponding author Dr. Zheng Sun, associate professor of medicine-endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism at Baylor. "We are interested in this gene because it is a 'druggable' component of the circadian clock with potential applications in the clinic. Rev-erb is expressed only during the day but not at night. When we started, we did not know where this was going to lead us."

The researchers first developed a mouse model by knocking out the Rev-erb gene in GABA neurons. They chose this approach because the gene's expression is highly enriched in a particular brain area called the suprachiasmatic nucleus that is mainly composed of GABA neurons.

An unexpected finding

"We observed something very interesting in these mice," Sun said. "They were glucose intolerant - that is they had high glucose levels - only in the evening. Mice are nocturnal, meaning that they become active in the evening as people do in the morning."

When the body awakes and takes in food, insulin is secreted from the pancreas to signal the body to lower blood sugar. Insulin is more effective in doing this job upon waking than at other times of the day. This high insulin sensitivity is probably because the body is anticipating feeding behaviors upon waking up. In mice, high insulin sensitivity occurs in the evening, while in people it occurs in the morning.

Sun and his colleagues found that the abnormal higher glucose levels observed in the evening in Rev-erb knockout mice resulted from an insufficient suppression of liver glucose production by insulin. Their data demonstrate an essential role of neural Rev-erb in regulating the hepatic insulin sensitivity rhythm independent of eating behaviors or basal hepatic glucose production.

Next, the researchers looked to understand how defects in Rev-erb gene expression in the brain can result in changes in the ability of the liver to respond to insulin. They discovered that the suprachiasmatic nucleus GABA neurons in Rev-erb knockout mice had a higher firing activity than those neurons of normal mice when the animals woke up, and that this neuronal hyperactivity was sufficient and necessary to cause glucose intolerance in the evening. In normal mice, these GABA neurons drop their firing activity in the evening, lowering sugar blood levels. Interestingly, by re-expressing Rev-erb back in the knockout mice, the researchers found that Rev-erb expression is only needed during the day, but not needed at night, which is in line with the highly oscillatory expression pattern of endogenous Rev-erb in normal condition.

Connecting with dawn phenomenon

Mice having higher glucose levels in the evening reminded Sun and his colleagues of dawn phenomenon observed in people with type 2 diabetes. "Given the similarities of the phenomenon in mice and people, we thought that maybe this gene that we are studying could be linked to the biology of dawn phenomena in diabetic patients," said Sun, a member of Baylor's Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Huffington Center on Aging.

In collaboration with Qilu Hospital of Shandong University in China, the researchers followed 27 type2 diabetes patients with continuous glucose monitoring. They found that, although the patients had diabetes with similar severity in terms of their basal glucose levels, obesity and other parameters, about half of the patients had dawn phenomenon while the other half did not.

"We collected the patients' blood at different times of the day and determined the expression of the Rev-erb gene in white blood cells, which has been reported to correlate well with the central clock in the brain," Sun said. "Interestingly, we found that the gene's expression followed a temporal pattern that was different between those with dawn phenomenon and those without," Sun said. "We propose that the altered temporal pattern of expression of this gene may explain dawn phenomena in people. It is possible that, in the future, a drug might be used to regulate this gene to treat the condition."

INFORMATION:

See the publication for a complete list of the contributors to this work and the financial sources of support.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-25

WASHINGTON (March 25, 2021)--Although demand for COVID-19 vaccines currently seems high, vaccine hesitancy could pose a major threat to public health efforts to end the pandemic, according to an editorial published today in the journal Science.

The authors, including David A. Broniatowski, associate director of the George Washington University Institute for Data, Democracy & Politics, point out that public sentiment towards vaccines are volatile in the face of events such as the recent controversy surrounding the AstraZeneca vaccine clinical trial data. For example, some people could develop safety concerns due to the news reporting about the AstraZeneca vaccine and then turn down the chance to ...

2021-03-25

Narcissism is driven by insecurity, and not an inflated sense of self, finds a new study by a team of psychology researchers. Its research, which offers a more detailed understanding of this long-examined phenomenon, may also explain what motivates the self-focused nature of social media activity.

"For a long time, it was unclear why narcissists engage in unpleasant behaviors, such as self-congratulation, as it actually makes others think less of them," explains Pascal Wallisch, a clinical associate professor in New York University's Department of Psychology and the senior author of the paper, which appears in the journal Personality and Individual Differences. "This has become quite prevalent in the age of social media--a behavior that's been coined 'flexing'.

"Our ...

2021-03-25

A study by prof. Bas van Bavel and prof. Marten Scheffer shows that throughout history, most disasters and pandemics have boosted inequality instead of levelling it. Whether such disastrous events function as levellers or not, depends on the distribution of economic wealth and political leverage within a society at the moment of crisis. Their findings on the historical effects of crises on equality in societies are now published open access in Nature HSS Communications.

It is often thought that the main levellers of inequality in societies were natural disasters such as epidemics or earthquakes, and social turmoil such as wars and ...

2021-03-25

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Materials that contain special polymer molecules may someday be able to warn us when they are about to fail, researchers said. Engineers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have improved their previously developed force-sensitive molecules, called mechanophores, to produce reversible, rapid and vibrant color change when a force is applied.

The new study led by postdoctoral researcher Hai Qian, materials science and engineering professor and head Nancy Sottos, and Beckman Institute of Advanced Science and Technology director Jeffrey Moore is published in the journal Chem.

Moore's team has been working with mechanophores for more than a decade, but past efforts have produced molecules that were slow to react and return to their original state, if at all. ...

2021-03-25

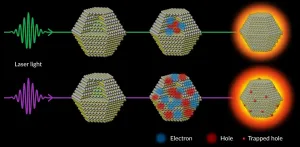

Bright semiconductor nanocrystals known as quantum dots give QLED TV screens their vibrant colors. But attempts to increase the intensity of that light generate heat instead, reducing the dots' light-producing efficiency.

A new study explains why, and the results have broad implications for developing future quantum and photonics technologies where light replaces electrons in computers and fluids in refrigerators, for example.

In a QLED TV screen, dots absorb blue light and turn it into green or red. At the low energies where TV screens operate, this conversion of light from one color to another is virtually 100% efficient. But at the higher excitation energies required for brighter screens and other ...

2021-03-25

In the year since the coronavirus pandemic upended how just about every person on the planet interacts with one another, video conferencing has become the de facto tool for group collaboration within many organizations. The prevalent assumption is that technology that helps to mimic face-to-face interactions via a video camera will be most effective in achieving the same results, yet there's little data to actually back up this presumption. Now, a new study challenges this assumption and suggests that non-visual communication methods that better synchronize and boost audio cues are in fact more effective.

Synchrony Promotes Collective Intelligence

Researchers from Carnegie Mellon's Tepper School of Business and the Department of Communication at the University of California, Santa ...

2021-03-25

Despite having remarkable utility in treating movement disorders such as Parkinson's disease, deep brain stimulation (DBS) has confounded researchers, with a general lack of understanding of why it works at some frequencies and does not at others. Now a University of Houston biomedical engineer is presenting evidence in Nature Communications Biology that electrical stimulation of the brain at higher frequencies (>100Hz) induces resonating waveforms which can successfully recalibrate dysfunctional circuits causing movement symptoms.

"We investigated the modulations in local ?eld potentials induced by electrical stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus (STN) at therapeutic and non-therapeutic frequencies in Parkinson's disease patients ...

2021-03-25

LA JOLLA--The glow of a panther's eyes in the darkness. The zig-zagging of a shark's dorsal fin above the water.

Humans are always scanning the world for threats. We want the chance to react, to move, to call for help, before danger strikes. Our cells do the same thing.

The innate immune system is the body's early alert system. It scans cells constantly for signs that a pathogen or dangerous mutation could cause disease. And what does it like to look for? Misplaced genetic material.

The building blocks of DNA, called nucleic acids, are supposed to be hidden away in the cell nucleus. Diseases can change that. Viruses churn out genetic material in parts of the cell where it's not supposed to be. Cancer cells do too.

"Cancer cells harbor damaged DNA," says ...

2021-03-25

New clues to a long-pursued drug target in cancer may reside within immune cells, researchers at the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center have discovered.

The findings, which appear in Nature Immunology, not only shed new light on cancer immunology, they also suggest clinical trials related to this key target -- an interaction that destabilizes the important p53 tumor suppressor protein -- may unnecessarily be excluding a large number of patients.

The researchers are optimistic that the findings could help make immunotherapy treatment more effective against ...

2021-03-25

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Warm river habitats appear to play a larger than expected role supporting the survival of cold-water fish, such as salmon and trout, a new Oregon State University-led study published today found.

The research has important implications for fish conservation strategies. A common goal among scientists and policymakers is to identify and prioritize habitat for cold-water fish that remains suitably cool during the summer, especially as the climate warms.

This implicitly devalues areas that are seasonally warm, even if they are suitable for fish most of the year, said Jonny Armstrong, lead author of the paper and an ecologist at Oregon State. He called this a "potentially severe blind spot for climate change adaptation."

"Coldwater ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Circadian clock gene Rev-erb linked to dawn phenomenon in type 2 diabetes