(Press-News.org) Using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen can be an effective way to produce clean-burning hydrogen fuel, with further benefits if that electricity is generated from renewable energy sources. But as water-splitting technologies improve, often using porous electrode materials to provide greater surface areas for electrochemical reactions, their efficiency is often limited by the formation of bubbles that can block or clog the reactive surfaces.

Now, a study at MIT has for the first time analyzed and quantified how bubbles form on these porous electrodes. The researchers have found that there are three different ways bubbles can form on and depart from the surface, and that these can be precisely controlled by adjusting the composition and surface treatment of the electrodes.

The findings could apply to a variety of other electrochemical reactions as well, including those used for the conversion of carbon dioxide captured from power plant emissions or air to form fuel or chemical feedstocks. The work is described today in the journal Joule, in a paper by MIT visiting scholar Ryuichi Iwata, graduate student Lenan Zhang, professors Evelyn Wang and Betar Gallant, and three others.

"Water-splitting is basically a way to generate hydrogen out of electricity, and it can be used for mitigating the fluctuations of the energy supply from renewable sources," says Iwata, the paper's lead author. That application was what motivated the team to study the limitations on that process and how they could be controlled.

Because the reaction constantly produces gas within a liquid medium, the gas forms bubbles that can temporarily block the active electrode surface. "Control of the bubbles is a key to realizing a high system performance," Iwata says. But little study had been done on the kinds of porous electrodes that are increasingly being studied for use in such systems.

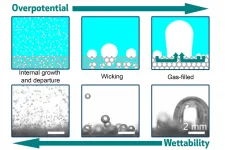

The team identified three different ways that bubbles can form and release from the surface. In one, dubbed internal growth and departure, the bubbles are tiny relative to the size of the pores in the electrode. In that case, bubbles float away freely and the surface remains relatively clear, promoting the reaction process.

In another regime, the bubbles are larger than the pores, so they tend to get stuck and clog the openings, significantly curtailing the reaction. And in a third, intermediate regime, called wicking, the bubbles are of medium size and are still partly blocked, but manage to seep out through capillary action.

The team found that the crucial variable in determining which of these regimes takes place is the wettability of the porous surface. This quality, which determines whether water spreads out evenly across the surface or beads up into droplets, can be controlled by adjusting the coating applied to the surface. The team used a polymer called PTFE, and the more of it they sputtered onto the electrode surface, the more hydrophobic it became. It also became more resistant to blockage by larger bubbles.

The transition is quite abrupt, Zhang says, so even a small change in wettability, brought about by a small change in the surface coating's coverage, can dramatically alter the system's performance. Through this finding, he says, "we've added a new design parameter, which is the ratio of the bubble departure diameter [the size it reaches before separating from the surface] and the pore size. This is a new indicator for the effectiveness of a porous electrode."

Pore size can be controlled through the way the porous electrodes are made, and the wettability can be controlled precisely through the added coating. So, "by manipulating these two effects, in the future we can precisely control these design parameters to ensure that the porous medium is operated under the optimal conditions," Zhang says. This will provide materials designers with a set of parameters to help guide their selection of chemical compounds, manufacturing methods and surface treatments or coatings in order to provide the best performance for a specific application.

While the group's experiments focused on the water-splitting process, the results should be applicable to virtually any gas-evolving electrochemical reaction, the team says, including reactions used to electrochemically convert captured carbon dioxide, for example from power plant emissions.

Gallant, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT, says that "what's really exciting is that as the technology of water splitting continues to develop, the field's focus is expanding beyond designing catalyst materials to engineering mass transport, to the point where this technology is poised to be able to scale." While it's still not at the mass-market commercializable stage, she says, "they're getting there. And now that we're starting to really push the limits of gas evolution rates with good catalysts, we can't ignore the bubbles that are being evolved anymore, which is a good sign."

INFORMATION:

The MIT team also included Kyle Wilke, Shuai Gong, and Mingfu He. The work was supported by Toyota Central R&D Labs, the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART), the U.S.-Egypt Science and Technology Joint Fund, and the Natural Science Foundation of China.

Written by David L. Chandler, MIT News Office

Additional background

Paper: "Bubble growth and departure modes on wettable-non-wettable porous foams in alkaline water splitting"

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2542435121000921

Limerick, Ireland, 26 March 2020: Researchers at Lero, the Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre for Software and University of Limerick (UL), have found video gamers can significantly improve their esport skills by training for just 10 minutes a day.

The research team at Lero's Esports Science Research Lab (ESRL) at UL also found novice gamers benefited most when they wore a custom headset delivering transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) for 20 minutes before training sessions.

Dr Mark Campbell, director of Lero's Esports Science Research Lab (ESRL) and senior lecturer in sports psychology at UL, said their work showed that neurostimulation could accelerate motor performance improvements specifically in novice esports ...

Patients with lupus are more likely to have metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance - both factors linked to heart disease - if they have lower vitamin D levels, a new study reveals.

Researchers believe that boosting vitamin D levels may improve control of these cardiovascular risk factors, as well as improving long-term outcomes for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Given that photosensitivity is a key feature of SLE, the scientists say that a combination of avoiding the sun, using high-factor sunblock and living in more northerly ...

What The Study Did: Insurance claims were used to assess patterns of telehealth use across surgical specialties before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors: Grace F.Chao, M.D., M.Sc., of the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of Michigan and Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor in Michigan, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0979)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions ...

What The Study Did: This article discusses possible pathogenic mechanisms of brain dysfunction in patients with COVID-19.

Authors: Maura Boldrini, M.D., Ph.D., of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0500)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial ...

Bariatric surgery can significantly reduce the risk of cancer--and especially obesity-related cancers--by as much as half in certain individuals, according to a study by researchers at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School's Center for Liver Diseases and Liver Masses.

The research, published in the journal Gastroenterology, is the first to show bariatric surgery significantly decreases the risk of cancer in individuals with severe obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The risk reduction is even more pronounced in individuals with NAFLD-cirrhosis, the researchers say.

"We knew that obesity leads to certain problems, including cancer, but no one ...

The alarm bells began ringing when dozens of eagles were found dead near an Arkansas lake.

Their deaths--and, later, the deaths of other waterfowl, amphibians and fish--were the result of a neurological disease that caused holes to form in the white matter of their brains. Field and laboratory research over nearly three decades has established the primary clues needed to solve this wildlife mystery: Eagle and waterfowl deaths occur in late fall and winter within reservoirs with excess invasive aquatic weeds, and birds can die within five days after arrival.

But until recently, the toxin that caused the disease, vacuolar myelinopathy, was unknown.

Now, after years spent identifying a new toxic blue-green algal (cyanobacteria) species and isolating ...

PITTSBURGH, March 26, 2021 - As evidence mounts supporting the use of monoclonal antibody treatment to reduce hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19, UPMC and University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine physician-scientists are sharing the health system's experience administering the life-saving medication.

In a report published today in the scientific journal Open Forum Infectious Diseases, the UPMC/Pitt team shares how it quickly established the largest and most equitable distribution network for COVID-19 monoclonal antibody infusions across Pennsylvania. The team today also reported preliminary results confirming the treatment reduced likelihood of hospitalization ...

EL PASO, Texas - Sreenath Chalil Madathil, Ph.D., assistant professor in industrial manufacturing and systems engineering (IMSE) at The University of Texas at El Paso, is working to streamline the process and ease the patient experience at COVID-19 vaccination clinics in the United States to ensure faster vaccine distribution.

Madathil led a team of UTEP faculty, staff and students who observed several of El Paso's drive-though and walk-in clinics in early 2021. The team identified areas that likely created bottlenecks, which produce delays and other issues. They used the information ...

A University of Florida study of middle-aged and older adults finds those who unknowingly carry methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, on their skin are twice as likely to die within the next decade as people who do not have the bacteria.

"Very few people who carry MRSA know they have it, yet we have found a distinct link between people with undetected MRSA and premature death," said the study's lead author Arch G. Mainous III, Ph.D., a professor in the department of health services research, management and policy at the UF College of Public Health and Health Professions, part of UF Health, the university's academic health center.

The findings suggest that routine screening for undetected ...

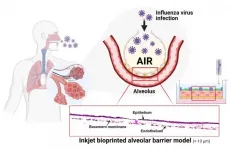

The warmer temperature and blooming flowers signal the arrival of spring. However, worries about respiratory diseases are also on the rise due to fine dust and viruses. The lung, which is vital to breathing, is rather challenging to create artificially for experimental use due to its complex structure and thinness. Recently, a POSTECH research team has succeeded in producing an artificial lung model using 3D printing.

Professor Sungjune Jung of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, and Professor Joo-Yeon Yoo and Ph.D. candidate Dayoon Kang of the Department of Life Sciences at POSTECH have together succeeded in creating ...