(Press-News.org) Female doctors who suffer domestic abuse can feel unable to get help due to perceptions that it "should not happen to a doctor" and a judgemental culture in medical settings, a new study suggests.

Victim-survivors who work as doctors often do not feel able to talk about abuse confidentially and fear the consequences of reporting it.

Researchers from the University of Southampton interviewed twenty-one female doctors who had previously left an abusive relationship about their experience of domestic abuse, barriers they faced when seeking help, and the impact on their work. The findings have been published in the British Journal of General Practice.

Dr Emily Donovan, who led the study from the University of Southampton's Primary Care Research Centre said: "Domestic abuse is a huge problem for women from all walks of life but I was surprised to hear through conversations how prevalent it seemed to be in the medical profession. Despite this, very little has been written about doctors who are victims, all the research seems to focus on how doctors help other victims of domestic abuse. So I wanted to find out more about how it affected these women at work and their experiences of seeking support."

1. "It shouldn't happen to a doctor"

Several participants expressed embarrassment and felt that, as doctors, they "should have known better" and that they are "supposed to be intelligent, strong women who are not vulnerable." This could also lead them to question how they would be able to help their patients whilst feeling as though they could not look after themselves.

Despite the perceptions that it should not happen to them, many of the victim-survivors said that the nature of their job actually made them more vulnerable to persistent domestic abuse. Because they work hard every day to resolve problems for others, it was natural for this determination to 'keep going' to continue in their personal lives. For some participants, routinely dealing with difficult and demanding colleagues normalised the poor treatment that they experienced at home, causing them to persist with relationships even after they had become abusive.

2. Hard to disclose problems or seek help from fellow health professionals.

The study identified a number of barriers to disclosing and seeking help, the main concerns being confidentiality, for example having to speak to health professionals who they know personally or professionally.

Many participants said that not fitting the stereotype of a female suffering domestic abuse caused disbelief from health professionals from whom they sought help as a patient. Some victim-survivors felt that health or social care professionals were quick to shut the conversations down, whilst some were threatened with being reported to the General Medical Council (GMC).

Problems in disclosure were particularly prominent when the abusive partner was also a health professional, which often deterred the victim-survivor from reporting the abuse through fear that they would not be believed due to their partner's status.

3. A "judgemental" medical culture

A culture of presenteeism in medical settings and perception that weakness is not tolerated also made it difficult to get the time off needed to access domestic abuse services during working hours.

When victim-survivors were able to speak to health professionals who would listen and validate that they were experiencing domestic abuse, it made a huge difference. Peer support groups were also extremely valuable in helping them understand that they were not alone and inspiring them to take action.

Speaking about how the medical profession can support its workers, Dr Donovan said, "A designated confidential service for doctor victim-survivors would give them access to support without the risk of meeting their patients and colleagues.

"The medical profession also needs to change its culture so that its workers feel that they can talk to each other more and that they are being looked after as well as their patients."

INFORMATION:

Education is considered one of the most critical personal capital investments. But formal educational attainment doesn't necessarily pay off in job satisfaction, according to new research from the University of Notre Dame.

In fact, there is almost no relationship between the two, according to "Does Educational Attainment Promote Job Satisfaction? The Bittersweet Trade-offs Between Job Resources, Demands and Stress," forthcoming in the Journal of Applied Psychology from Brittany Solomon (Hall), assistant professor of management, and Dean Shepherd, the Ray and Milann Siegfried ...

Researchers at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center have developed a new framework for different factors influencing how a child's brain is "wired" to learn to read before kindergarten.

This may help pediatric providers identify risks when the brain is most responsive to experiences and interventions. This "eco-bio-developmental" model of emergent literacy, described in the journal JAMA Pediatrics, reinforces the potential of early screening, prevention, and intervention during pediatric clinic visits in early childhood.

This kind of model is advocated by the American Academy ...

Remote monitoring using airborne devices such as drones or satellites could revolutionise the effectiveness of nature-based solutions (NBS) that protect communities from devastating natural hazards such as floods, storms and landslides, say climate change experts from the University of Surrey.

Grey structural measures (a collective term for engineering projects that use concrete and steel) like floodgates, dams, dikes and sea walls are still the most common methods to guard against natural hazards. However, these 'grey measures' are expensive and lack the long-term flexibility and sustainability needed to help communities manage their growing population and address the planet's ongoing struggle against urbanisation ...

Scientists have discovered that tracking malaria as it develops in humans is a powerful way to detect how the malaria parasite causes a range of infection outcomes in its host.

The study, found some remarkable differences in the way individuals respond to malaria and raises fresh questions in the quest to understand and defeat the deadly disease.

Malaria, caused by the parasite - Plasmodium falciparum - is a huge threat to adults and children in the developing world. Each year, around half a million people die from the disease and another 250 million are infected. Malaria parasites are spread to humans through the bites of infected mosquitoes.

The outcomes that follow a malaria infection can vary from no symptoms to life-threatening ...

A team of scientists has been using DESY's X-ray source PETRA III to analyse the structural changes that take place in an egg when you cook it. The work reveals how the proteins in the white of a chicken egg unfold and cross-link with each other to form a solid structure when heated. Their innovative method can be of interest to the food industry as well as to the broad field of research surrounding protein analysis. The cooperation of two groups, headed by Frank Schreiber from the University of Tübingen and Christian Gutt from the University of Siegen, with scientists at DESY and European XFEL reports the research in two articles in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Eggs are among the most versatile food ingredients. They can take the form of a gel or ...

Adding the nutrient selenium to diets protects against obesity and provides metabolic benefits to mice, according to a study published today in eLife.

The results could lead to interventions that reproduce many of the anti-aging effects associated with dietary restriction while also allowing people to eat as normal.

Several types of diet have been shown to increase healthspan - that is, the period of healthy lifespan. One of the proven methods of increasing healthspan in many organisms, including non-human mammals, is to restrict dietary intake of an amino acid ...

Humans are creating or exacerbating the environmental conditions that could lead to further pandemics, new University of Sydney research finds.

Modelling from the Sydney School of Veterinary Science suggests pressure on ecosystems, climate change and economic development are key factors associated with the diversification of pathogens (disease-causing agents, like viruses and bacteria). This has potential to lead to disease outbreaks.

The research, by Dr Balbir B Singh, Professor Michael Ward, and Associate Professor Navneet Dhand, is published in the international journal, Transboundary and Emerging Diseases.

They found a greater diversity ...

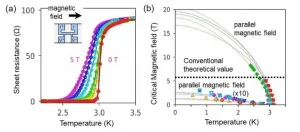

Superconductivity is known to be easily destroyed by strong magnetic fields. NIMS, Osaka University and Hokkaido University have jointly discovered that a superconductor with atomic-scale thickness can retain its superconductivity even when a strong magnetic field is applied to it. The team has also identified a new mechanism behind this phenomenon. These results may facilitate the development of superconducting materials resistant to magnetic fields and topological superconductors composed of superconducting and magnetic materials.

Superconductivity has been used in various technologies, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ...

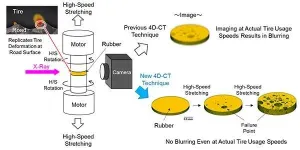

Sumitomo Rubber Industries, Ltd (SRI) and Tohoku University teamed up to increase the speed of 4-Dimensional Computed Tomography (4D-CT) a thousand-fold, making it possible to observe rubber failure in tires in real-time.

This breakthrough will accelerate the development of new tire materials to provide super wear resistance, greater environmental friendliness, and longer service life. It will also aid significantly in the advancement of smart tires.

SRI initially developed 4D-CT as part of the ADVANCED 4D NANO DESIGN, a new materials development technology unveiled in 2015 that enables highly accurate analysis and simulation of the rubber's internal structure from the micro to nanoscale. This analysis ultimately ...

An evolutionary mystery that had eluded molecular biologists for decades may never have been solved if it weren't for the COVID-19 pandemic.

"Being stuck at home was a blessing in disguise, as there were no experiments that could be done. We just had our computers and lots of time," says Professor Paul Curmi, a structural biologist and molecular biophysicist with UNSW Sydney.

Prof. Curmi is referring to research published this month in Nature Communications that details the painstaking unravelling and reconstruction of a key protein in a single-celled, photosynthetic organism called a cryptophyte, a type of algae that evolved over a billion years ago.

Up until now, how cryptophytes acquired the proteins ...