(Press-News.org) Scientists have discovered that tracking malaria as it develops in humans is a powerful way to detect how the malaria parasite causes a range of infection outcomes in its host.

The study, found some remarkable differences in the way individuals respond to malaria and raises fresh questions in the quest to understand and defeat the deadly disease.

Malaria, caused by the parasite - Plasmodium falciparum - is a huge threat to adults and children in the developing world. Each year, around half a million people die from the disease and another 250 million are infected. Malaria parasites are spread to humans through the bites of infected mosquitoes.

The outcomes that follow a malaria infection can vary from no symptoms to life-threatening disease and death. The precise reasons why people respond in different ways to the same parasite infection are still unknown, experts say.

Researchers from the University of Edinburgh, in collaboration with teams at the Universities of Oxford and Glasgow and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, explored infection outcomes in 14 volunteers who were injected with malaria parasites.

Scientists studied how the volunteers responded to the parasites over the course of 10 days. The group were then treated with antimalarial drugs to cure the infection before there was any risk of them developing severe symptoms.

The study, published in eLife, found that the immune systems in about half of the volunteers were rapidly alerted to the presence of parasites and began to produce signals to mobilise host defences.

These volunteers began to suffer symptoms of malaria such as fever and headache. The other volunteers, however, either showed no sign of immune activation, or else started to develop responses to dampen their body's immune response. These volunteers did not develop malaria symptoms.

Dr Phil Spence, Sir Henry Dale Fellow, Institute of Infection and Immunology Research, University of Edinburgh and one of the project leads, said: "It looks like most of the variation in malaria is due to intrinsic differences between people in how they respond to infection.

"We need to do further work to tease out the underlying factors responsible for immune variation, such as investigating human genetics and prior experience of other infections."

The study also asked whether variation in parasite growth rate, the rate at which a parasite replicates within the body, or virulence factors, the properties of a parasite thought to make an infection more severe, were different in the volunteers and if this had a bearing on infection outcomes.

Surprisingly, the researchers found that although parasite growth rates did vary substantially between volunteers, this was not linked to outcomes. For example, a volunteer could have a small number of parasites with a strong immune reaction or have a large number with no symptoms.

Furthermore, monitoring the parasite virulence factors through time, in particular a family of molecules called group A var genes, showed no differences between volunteers and no changes over the course of infection.

Professor Alex Rowe, Personal Chair of Molecular Medicine, Institute of Infection and Immunology Research, University of Edinburgh and project co-lead, said: "The biggest surprise from our study was that there was no variation in expression of the parasite virulence factors.

"Current theory, based on data from infected patients in malarious countries, suggested that parasites expressing group A var genes would rapidly come to dominate as the infection progressed, but this was not seen in our volunteers.

"There are many possible reasons for this - maybe a parasite collected more recently from a field site would give a different result, or maybe longer infection times are needed so the host immune response can influence these changes."

The unexpected results from this study shows the power of human volunteer studies to raise new questions and give novel insights into diseases that have been studied in other ways for many decades, according to the team.

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust and the UK Medical Research Council.

For further information, please contact: Rhona Crawford, Press and PR Office, 0131 650 2246, rhona.crawford@ed.ac.uk

A team of scientists has been using DESY's X-ray source PETRA III to analyse the structural changes that take place in an egg when you cook it. The work reveals how the proteins in the white of a chicken egg unfold and cross-link with each other to form a solid structure when heated. Their innovative method can be of interest to the food industry as well as to the broad field of research surrounding protein analysis. The cooperation of two groups, headed by Frank Schreiber from the University of Tübingen and Christian Gutt from the University of Siegen, with scientists at DESY and European XFEL reports the research in two articles in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Eggs are among the most versatile food ingredients. They can take the form of a gel or ...

Adding the nutrient selenium to diets protects against obesity and provides metabolic benefits to mice, according to a study published today in eLife.

The results could lead to interventions that reproduce many of the anti-aging effects associated with dietary restriction while also allowing people to eat as normal.

Several types of diet have been shown to increase healthspan - that is, the period of healthy lifespan. One of the proven methods of increasing healthspan in many organisms, including non-human mammals, is to restrict dietary intake of an amino acid ...

Humans are creating or exacerbating the environmental conditions that could lead to further pandemics, new University of Sydney research finds.

Modelling from the Sydney School of Veterinary Science suggests pressure on ecosystems, climate change and economic development are key factors associated with the diversification of pathogens (disease-causing agents, like viruses and bacteria). This has potential to lead to disease outbreaks.

The research, by Dr Balbir B Singh, Professor Michael Ward, and Associate Professor Navneet Dhand, is published in the international journal, Transboundary and Emerging Diseases.

They found a greater diversity ...

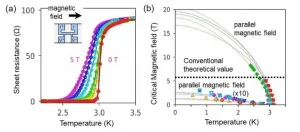

Superconductivity is known to be easily destroyed by strong magnetic fields. NIMS, Osaka University and Hokkaido University have jointly discovered that a superconductor with atomic-scale thickness can retain its superconductivity even when a strong magnetic field is applied to it. The team has also identified a new mechanism behind this phenomenon. These results may facilitate the development of superconducting materials resistant to magnetic fields and topological superconductors composed of superconducting and magnetic materials.

Superconductivity has been used in various technologies, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ...

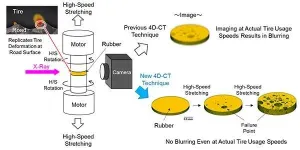

Sumitomo Rubber Industries, Ltd (SRI) and Tohoku University teamed up to increase the speed of 4-Dimensional Computed Tomography (4D-CT) a thousand-fold, making it possible to observe rubber failure in tires in real-time.

This breakthrough will accelerate the development of new tire materials to provide super wear resistance, greater environmental friendliness, and longer service life. It will also aid significantly in the advancement of smart tires.

SRI initially developed 4D-CT as part of the ADVANCED 4D NANO DESIGN, a new materials development technology unveiled in 2015 that enables highly accurate analysis and simulation of the rubber's internal structure from the micro to nanoscale. This analysis ultimately ...

An evolutionary mystery that had eluded molecular biologists for decades may never have been solved if it weren't for the COVID-19 pandemic.

"Being stuck at home was a blessing in disguise, as there were no experiments that could be done. We just had our computers and lots of time," says Professor Paul Curmi, a structural biologist and molecular biophysicist with UNSW Sydney.

Prof. Curmi is referring to research published this month in Nature Communications that details the painstaking unravelling and reconstruction of a key protein in a single-celled, photosynthetic organism called a cryptophyte, a type of algae that evolved over a billion years ago.

Up until now, how cryptophytes acquired the proteins ...

About 61% of Americans have had at least one Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE), experts' formal term for a traumatic childhood event.

ACEs--which may include abuse, neglect and severe household dysfunction--often lead to psychological and social struggles that reach into adulthood, making ACEs a major public health challenge. But the long-term consequences of ACEs are just beginning to be understood in detail. To fill in the picture, two recent BYU studies analyzed how ACEs shape adolescents' delinquent behaviors as well as fathers' parenting approaches.

ACEs ...

An international survey that included 600 smokers in the UK has found that cessation messaging focused on easing the burden on our health system is most effective in encouraging people to quit.

The research, which was conducted in April-May 2020, randomly assigned participants to view one of four quit smoking messages, two of which explicitly referenced health implications and COVID-19, one referred more vaguely to risk of chest infection, and one highlighted financial motivations for quitting.

"We wanted to explore the effectiveness of smoking cessation messaging at a time when health systems the world over are beleaguered, and all our ...

Replacing regular common salt consumed by hypertensive patients in rural areas with a salt substitute can have a significant impact in terms of lowering their blood pressure, a new study by The George Institute for Global Health has revealed.

Researchers found that substituting a small part of the sodium in salt with potassium without altering the taste led to a substantial reduction in systolic blood pressure in these patients, supporting salt substitution as an effective, low-cost intervention for lowering blood pressure in rural India.

The study entitled "Effects of reduced-sodium added-potassium salt substitute on blood pressure in rural Indian hypertensive patients: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial" provides the first-of-its-kind evidence from ...

In a new study published in the Cell Research, Chen-Yu Zhang's group at Nanjing University reports "In vivo self-assembled small RNA is the new generation of RNAi therapeutics".

The development of RNAi therapy has undergone two major stages, direct injection of synthetic siRNAs and delivery with artificial vehicles; both have not realized the full therapeutic potential of RNAi in clinic. In this study, Chen-Yu Zhang's group reprogram host liver with genetic circuits to direct the synthesis and self-assembly of siRNAs into secretory exosomes. In vivo assembled siRNAs are systematically distributed to multiple tissues or targeted to specific tissues (e.g., brain), inducing potent target gene silencing in these tissues. The therapeutic value of this strategy is demonstrated ...