(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA -- More than just a sign of illness, mucus is a critical part of our body's defenses against disease. Every day, our bodies produce more than a liter of the slippery substance, covering a surface area of more than 400 square meters to trap and disarm microbial invaders.

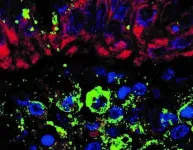

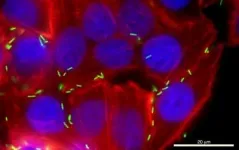

Mucus is made from mucins -- proteins that are decorated with sugar molecules. Many scientists are trying to create synthetic versions of mucins in hopes of replicating their beneficial traits. In a new study, researchers from MIT have now generated synthetic mucins with a polymer backbone that more accurately mimic the structure and function of naturally occurring mucins. The team also showed that these synthetic mucins could effectively neutralize the bacterial toxin that causes cholera.

The findings could help give researchers a better idea of which features of mucins contribute to different functions, especially their antimicrobial functions, says Laura Kiessling, the Novartis Professor of Chemistry at MIT. Replicating those functions in synthetic mucins could eventually lead to new ways to treat or prevent infectious disease, and such materials may be less likely to lead to the kind of resistance that occurs with antibiotics, she says.

"We would really like to understand what features of mucins are important for their activities, and mimic those features so that you could block virulence pathways in microbes," says Kiessling, who is the senior author of the new study.

Kiessling's lab worked on this project with Katharina Ribbeck, the Mark Hyman, Jr. Career Development Professor of Biological Engineering, and Richard Schrock, the F.G. Keyes Professor Emeritus of Chemistry, who are also authors of the paper. The lead authors of the paper, which appears today in ACS Central Science, are former MIT graduate student Austin Kruger and MIT postdoc Spencer Brucks.

Inspired by mucus

Kiessling and Ribbeck joined forces to try to create mucus-inspired materials in 2018, with funding from a Professor Amar G. Bose Research Grant. The primary building blocks of mucus are mucins -- long, bottlebrush-like proteins with many sugar molecules called glycans attached. Ribbeck has discovered that these mucins disrupt many key functions of infectious bacteria, including their ability to secrete toxins, communicate with each other, and attach to cellular surfaces.

Those features have led many scientists to try to generate artificial versions that could help prevent or treat bacterial infection. However, mucins are so large that it has been difficult to replicate their structure accurately. Each mucin polymer has a long backbone consisting of thousands of amino acids, and many different glycans can be attached to these backbones.

In the new study, the researchers decided to focus on the backbone of the polymer. To try to replicate its structure, they used a reaction called ring-opening metathesis polymerization. During this type of reaction, a carbon-containing ring is opened up to form a linear molecule containing a carbon-carbon double bond. These molecules can then be joined together to form long polymers.

In 2005, Schrock shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work developing catalysts that can drive this type of reaction. Later, he developed a catalyst that could yield specifically the "cis" configuration of the products. Each carbon atom in the double bond usually has one other chemical group attached to it, and in the cis configuration, both of these groups are on the same side of the double bond. In the "trans" configuration, the groups are on opposite sides.

To create their polymers, the researchers used Schrock's catalyst, which is based on tungsten, to form cis versions of mucin mimetic polymers. They compared these polymers to those produced by a different, ruthenium-based catalyst, which creates trans versions. They found that the cis versions were much more similar to natural mucins -- that is, they formed very elongated, water-soluble polymers. In contrast, the trans polymers formed globules that clumped together instead of stretching out.

Mimicking mucins

The researchers then tested the synthetic mucins' ability to mimic the functions of natural mucins. When exposed to the toxin produced by Vibrio cholerae, the elongated cis polymers were much better able to capture the toxin than the trans polymers, the researchers found. In fact, the synthetic cis mucin mimics were even more effective than naturally occurring mucins.

The researchers also found that their elongated polymers were much more soluble in water than the trans polymers, which could make them useful for applications such as eye drops or skin moisturizers.

Now that they can create synthetic mucins that effectively mimic the real thing, the researchers plan to study how mucins' functions change when different glycans are attached to the backbones. By altering the composition of the glycans, they hope to develop synthetic mucins that can dampen virulence pathways of a variety of microbes.

"We're thinking about ways to even better mimic mucins, but this study is an important step in understanding what's relevant," Kiessling says.

INFORMATION:

In addition to the Bose grant, the research was funded by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, the National Science Foundation, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

A study conducted at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, shows that compounds produced by gut microbiota (bacteria and other microorganisms) during fermentation of insoluble fiber from dietary plant matter do not affect the ability of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 to enter and replicate in cells lining the intestines. However, while in vitro treatment of cells with these molecules did not significantly influence local tissue infection, it reduced the expression of a gene that plays a key role in viral cell entry and a cytokine receptor that favors inflammation.

An ...

HERSHEY, Pa. -- Stress, increased free time and feelings of boredom may have contributed to an increase in the number of cigarettes smoked per day during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic by nearly a third of surveyed Pennsylvania smokers. Penn State College of Medicine researchers said understanding risk factors and developing new strategies for smoking cessation and harm reduction may help public health officials address concerning trends in tobacco use that may have developed as a result of the pandemic.

Jessica Yingst, assistant professor of public health sciences and Penn State Cancer Institute researcher, said smokers who increased the number of cigarettes they smoked per day could be at greater risk of dependence and have a more difficult ...

March 30, 2021 - As cancer survival rates improve, more people are living with the aftereffects of cancer treatment. For some patients, these issues include chronic radiation-induced skin injury - which can lead to potentially severe cosmetic and functional problems.

Recent studies suggest a promising new approach in these cases, using fat grafting procedures to unleash the healing and regenerative power of the body's natural adipose stem cells (ASCs). "Preliminary evidence suggests that fat grafting can make skin feel and look healthier, restore lost soft tissue volume, and help alleviate pain and fibrosis in patients with radiation-induced skin injury ...

Giant trees in tropical forests, witnesses to centuries of civilization, may be trapped in a dangerous feedback loop according to a new report in Nature Plants from researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama and the University of Birmingham, U.K. The biggest trees store half of the carbon in mature tropical forests, but they could be at risk of death as a result of climate change--releasing massive amounts of carbon back into the atmosphere.

Evan Gora, STRI Tupper postdoctoral fellow, studies the role of lightning in tropical forests. Adriane Esquivel-Muelbert, lecturer at the University of Birmingham, studies the effects of climate change in the Amazon. The two teamed up ...

PULLMAN, Wash. - Washington State University researchers have discovered a protein that could be key to blocking the most common bacterial cause of human food poisoning in the United States.

Chances are, if you've eaten undercooked poultry or cross contaminated food by washing raw chicken, you may be familiar with the food-borne pathogen.

"Many people that get sick think, 'oh, that's probably Salmonella,' but it is even more likely it's Campylobacter," said Nick Negretti ('20 Ph.D.), a lead member of the research team in Michael Konkel's Laboratory in WSU's School of Molecular Biosciences.

According to a study on the research recently published ...

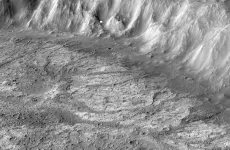

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Researchers from Brown University have discovered a previously unknown type of ancient crater lake on Mars that could reveal clues about the planet's early climate.

In a study published in Planetary Science Journal, a research team led by Brown Ph.D. student Ben Boatwright describes an as-yet unnamed crater with some puzzling characteristics. The crater's floor has unmistakable geologic evidence of ancient stream beds and ponds, yet there's no evidence of inlet channels where water could have entered the crater from outside, and no evidence ...

Judges don't do court stenography. CEOs don't take minutes at meetings. So why do we expect doctors and other health care providers to spend hours recording notes -- something experts know contributes to burnout?

"Having them do so much clerical work doesn't make sense," said Lisa Merlo, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and director of wellness programs at the University of Florida College of Medicine. "In order to improve the health care experience for everyone, we need to help them focus more on the actual practice of medicine."

Physician burnout affects patients, too. Stressed doctors are less compassionate and more likely to make mistakes. Clinicians who leave the field or cut back hours reduce patient access ...

Mount Sinai researchers have found that a widely available and inexpensive drug targeting inflammatory genes has reduced morbidity and mortality in mice infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. In a study published today in the journal Cell, the team reported that the drug, Topotecan (TPT), inhibited the expression of inflammatory genes in the lungs of mice as late as four days after infection, a finding with potential implications for treatment of humans.

"So far, in pre-clinical models of SARS-CoV-2, there are no therapies--either antiviral, antibody, or plasma--shown to reduce the SARS-CoV-2 disease burden when administered after more than one day post-infection" says senior author Ivan Marazzi, PhD, Associate Professor of Microbiology ...

Research into the diets of a large number of the world's carnivores has been made publicly available through a free, online database created by a PhD student at the University of Sussex.

From stoats in the UK to tigers in India, users are now able to search for detailed information about the diets of species in different geographical locations around the globe.

Created by doctoral student Owen Middleton, CarniDIET is an open-access database which aims to catalogue the diets of the world's carnivores by bringing together past peer-reviewed research. He hopes it will be a useful resource for conservationists and researchers, as well as educators and nature-lovers alike.

Owen said: "There is so much information out ...

A simple plastic water bottle isn't so simple when it comes to the traditional manufacturing process. To appear in its final form, it has to go through a multi-step journey of synthetic procedure, casting, and molding. But what if materials scientists could tap into the same biological mechanisms that create the ridges on our fingertips or the spots on a cheetah in order to manufacture something like a water bottle?

A research paper titled END ...