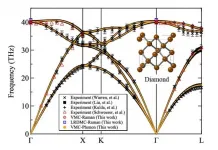

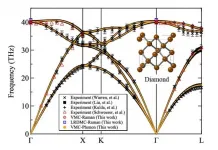

A successful phonon calculation within the Quantum Monte Carlo framework

Scientists expand the scope of the quantum Monte Carlo framework by reducing the error in calculation of atomic forces in solids

2021-03-31

(Press-News.org) Ishikawa, Japan - The focus and ultimate goal of computational research in materials science and condensed matter physics is to solve the Schrödinger equation--the fundamental equation describing how electrons behave inside matter--exactly (without resorting to simplifying approximations). While experiments can certainly provide interesting insights into a material's properties, it is often computations that reveal the underlying physical mechanism. However, computations need not rely on experimental data and can, in fact, be performed independently, an approach known as "ab initio calculations". The density functional theory (DFT) is a popular example of such an approach.

For most material scientists and condensed matter physicists, DFT calculations are the bread and butter of their profession. However, despite being a powerful technique, DFT has had limited success with "strongly correlated materials"--materials with unusual electronic and magnetic properties. These materials, while interesting on their own, also possess technological useful properties, a fact that strongly motivates an ab initio framework suited to describe them.

To that end, a framework known as "ab initio quantum Monte Carlo" (QMC) has shown considerable promise and is expected to be the next generation of electronic structure calculations due to its superiority over DFT. However, even QMC is largely restricted to calculations of energy and atomic forces, limiting its utility in computing useful material properties.

Now, in a breakthrough study published in Physical Review B (Editors' Suggestion), scientists have taken things to the next level based on an approach that allows them to reduce the statistical error in atomic force evaluation by two orders of magnitude and subsequently speeds up the computation by a factor of 104! "The drastic reduction in computational time will greatly expand the range of QMC calculations and enable highly accurate prediction of atomic properties of materials that have been difficult to handle," observes Assistant Professor Kousuke Nakano from Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (JAIST), who, along with his colleagues Prof. Ryo Maezono from JAIST, Prof. Sandro Sorella from International School for advanced Studies (SISSA), Italy, and Dr. Tommaso Morresi and Prof. Michele Casula from Sorbonne Université, France, led this groundbreaking achievement.

The team applied their developed method to calculate the atomic vibrations of diamond, a typical reference material, as a proof-of-concept and showed that the results were consistent with experimental values. To perform these calculations, they used a large computer, Cray-XC40, located at the Research Center for Advanced Computing Infrastructure at Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (JAIST), Japan, along with another located at RIKEN, Japan. The team made use of a QMC software package called "TurboRVB", initially launched by Prof. Sorella and Prof. Casula and developed later by Prof. Nakano along with others, to perform phonon dispersion calculations for diamond that were previously inaccessible, greatly expanding its scope.

Prof. Nakano looks forward to the applications of QMC in materials informatics (MI), a field dedicated to the design and search for novel materials using techniques of information science and computational physics. "While MI is currently governed by DFT, the rapid developments in computer performance, such as the exascale supercomputer, will help QMC gain popularity. In that regard, our developed method is going to be very useful for designing novel materials with real-life applications," concludes an optimistic Dr. Nakano.

INFORMATION:

About Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Japan

Founded in 1990 in Ishikawa prefecture, the Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (JAIST) was the first independent national graduate school in Japan. Now, after 30 years of steady progress, JAIST has become one of Japan's top-ranking universities. JAIST counts with multiple satellite campuses and strives to foster capable leaders with a state-of-the-art education system where diversity is key; about 40% of its alumni are international students. The university has a unique style of graduate education based on a carefully designed coursework-oriented curriculum to ensure that its students have a solid foundation on which to carry out cutting-edge research. JAIST also works closely both with local and overseas communities by promoting industry-academia collaborative research.

About Kousuke Nakano from Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Japan

Dr. Kousuke Nakano is an Assistant Professor at the School of Information Science at Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (JAIST), Japan since 2019. He obtained his B.Sc. and M.Sc. in engineering from Kyoto University in 2012 and 2014, respectively, and his Ph.D. in Computer and Information Science from JAIST in 2017. His research interests comprise Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) simulations, Density Functional Theory (DFT), and material informatics. He currently studies first-principle QMC calculations with a QMC software named "TurboRVB" that he helped develop. As a young and dynamic researcher, he has 28 papers to his credit with over 500 citations.

Funding information

Computational resources were provided from the facilities of Research Center for Advanced Computing Infrastructure at Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (JAIST), from PRACE Project No. 2019204934, and from RIKEN (the supercomputer Fugaku) through the HPCI System Re- search Project (Project ID: hp200164). This study was funded by French state funds managed by the ANR within the Investissements d'Avenir programme under reference ANR-11-IDEX-0004-02, and more specifically within the framework of the Cluster of Excellence MATISSE led by Sorbonne University, the Simons Foundation and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (No. 16H06439), MEXT-KAKENHI (19H04692 and 16KK0097), Toyota Motor Corporation, Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR-AOARD/FA2386-17-1-4049; FA2386-19-1-4015), JSPS Bilateral Joint Projects (with India DST), and PRIN 2017BZPKSZ.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-31

A new report is highlighting ways we can fight COVID-19 while indoors during cold weather periods.

At the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, there was a lack of empirical evidence on the virus's airborne transmission. However, an increasing body of evidence - gathered particularly from poorly ventilated environments - has given the scientific community a better understanding of how the disease progresses. Information on the asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic transmission of the virus strongly supports the case for airborne transmission of COVID-19.

In a study published by the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society A, scientists from the University of Surrey, together with other members of the Royal Society's Rapid Action in Modelling ...

2021-03-31

Skyrmions - tiny magnetic vortices - are considered promising candidates for tomorrow's information memory devices which may be able to achieve enormous data storage and processing capacities. A research team led by the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) has developed a method to grow a particular magnetic thin-film material that hosts these magnetic vortices. A central aspect of this new method is the abrupt heating of the material with short, very bright flashes of light, as the international team, consisting of scientists from HZDR, the Leibniz Institute for Solid State and Materials Research Dresden, TU Dresden (TUD), and Chinese partners, describes in the journal Advanced Functional Materials (DOI: 10.1002/adfm.202009723).

In 2009, a research team had made a remarkable discovery: ...

2021-03-31

New research by the University of Kent has found that using low-cost psychological interventions can reduce vehicle engine idling and in turn improve air quality, especially when there is increased traffic volume at railway level crossings.

A team of psychologists led by Professor Dominic Abrams, Dr Tim Hopthrow and Dr Fanny Lalot at the University's School of Psychology, found that using carefully worded road signage can decrease the number of drivers leaving engines idling during queues at crossing barriers.

The research, which was funded by ...

2021-03-31

Helsinki, Finland -- The EU will be home to 30 million electric cars by 2030 and the European Commission is preparing tough targets for recycling these and other batteries. Yet the impacts of battery recycling, especially for the sizeable lithium-ion batteries of the electric cars soon filling our streets, has been largely unstudied.

In a new study, researchers at Aalto University have investigated the environmental effects of a hydrometallurgical recycling process for electric car batteries. Using simulation-based life-cycle analysis, they considered energy and water consumption, as well as process emissions.

'Battery recycling processes are still developing, so their environmental footprints haven't yet been studied in detail. To be beneficial, recycling must be ...

2021-03-31

The nucleus is the headquarters of a cell and molecules constantly move across the nuclear membrane through pores. The transport of these molecules is both selective and fast; some 1,000 molecules per second can move in or out. Scientists from the University of Groningen and Delft University of Technology, both in the Netherlands, and a colleague from the Swedish Chalmers University of Technology, have developed an artificial model of these pores using simple design rules, which enabled them to study how this feat is accomplished. Their results were published on 31 March in Nature Communications.

Nuclear pores are extremely complicated structures. The pore itself is a big protein complex and the opening of the pore is filled with a dense network of ...

2021-03-31

First study in bereaved relatives' experience during Covid-19 pandemic lockdown published today

The study makes important recommendations for health and social care professionals providing end-of-life-care

Bereaved families highlighted their need for practical and emotional support when a family member was at end of life

The study found families have increased communication needs when a family member was at end of life, encompassing holistic as well as clinical connections

Phone calls between patients and their relatives should be prioritised during the pandemic to allow loved ones to say goodbye, a new study providing recommendations to healthcare professionals has suggested.

The ...

2021-03-31

Gustavo Aguirre and William Beltran, veterinary ophthalmologists and vision scientists at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, have studied a wide range of different retinal blinding disorders. But the one caused by mutations in the NPHP5 gene, leading to a form of Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), is one of the most severe.

"Children with this disorder are not visual," says Aguirre. "They have a wandering, searching look on their faces and are usually diagnosed at a young age."

A nearly identical disease naturally occurs in dogs. In a new paper in the journal Molecular Therapy, Aguirre, Beltran, and colleagues at Penn and other institutions have demonstrated that a canine gene therapy can restore both normal structure and function to the retina's ...

2021-03-31

University of California, Irvine, biologists have discovered that plants influence how their bacterial and fungal neighbors react to climate change. This finding contributes crucial new information to a hot topic in environmental science: in what manner will climate change alter the diversity of both plants and microbiomes on the landscape? The paper appears in Elementa: Sciences of the Anthropocene.

The research took place at the Loma Ridge Global Change Experiment, a decade-long study in which scientists simulate the impacts of climate change on neighboring grasslands and coastal scrublands in Southern California. Experimental treatments there include nitrogen addition, a common result of local fossil fuel burning, ...

2021-03-31

The human brain regions responsible for speech and communication keep our world running by allowing us to do things like talk with friends, shout for help in an emergency and present information in meetings.

However, scientific understanding of just how these parts of the brain work is limited. Consequently, knowledge of how to improve challenges such as speech impediments or language acquisition is limited as well.

Using an ultra-lightweight, wireless implant, a University of Arizona team is researching songbirds - one of the few species that share humans' ability to learn new vocalizations - to improve scientific ...

2021-03-31

Cone snails aren't glamorous. They don't have svelte waistlines or jaw-dropping good looks. Yet, some of these worm-hunting gastropods are the femme fatales or lady killers of the undersea world, according to a new study conducted by an international team of researchers, including University of Utah Health scientists.

The researchers say the snails use a previously undetected set of small molecules that mimic the effects of worm pheromones to drive marine worms into a sexual frenzy, making it easier to lure them out of their hiding places so the snails can gobble them up.

"In essence, these cone snails have found a way to turn the natural sex drive of their prey into a lethal weapon," says Eric W. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] A successful phonon calculation within the Quantum Monte Carlo framework

Scientists expand the scope of the quantum Monte Carlo framework by reducing the error in calculation of atomic forces in solids