(Press-News.org) A new study has found the first evidence of sophisticated breathing organs in 450-million-year-old sea creatures. Contrary to previous thought, trilobites were leg breathers, with structures resembling gills hanging off their thighs.

Trilobites were a group of marine animals with half-moon-like heads that resembled horseshoe crabs, and they were wildly successful in terms of evolution. Though they are now extinct, they survived for more than 250 million years -- longer than the dinosaurs.

Thanks to new technologies and an extremely rare set of fossils, scientists from UC Riverside can now show that trilobites breathed oxygen and explain how they did so. Published in the journal Science Advances, these findings help piece together the puzzle of early animal evolution.

"Up until now, scientists have compared the upper branch of the trilobite leg to the non-respiratory upper branch in crustaceans, but our paper shows, for the first time, that the upper branch functioned as a gill," said Jin-Bo Hou, a UCR paleontology doctoral student who led the research.

Among the oldest animals on earth, this work helps situate trilobites on the evolutionary tree more securely in between older arthropods, a large group of animals with exoskeletons, and crustaceans.

The research was possible, in part, because of unusually preserved fossil specimens. There are more than 22,000 trilobite species that have been discovered, but the soft parts of the animals are visible in only about two dozen.

"These were preserved in pyrite -- fool's gold -- but it's more important than gold to us, because it's key to understanding these ancient structures," said UCR geology professor and paper co-author Nigel Hughes.

A CT scanner was able to read the differences in density between the pyrite and the surrounding rock and helped create three-dimensional models of these rarely seen gill structures.

"It allowed us to see the fossil without having to do a lot of drilling and grinding away at the rock covering the specimen," said paleontologist Melanie Hopkins, a research team member at the American Museum of Natural History.

"This way we could get a view that would even be hard to see under a microscope -- really small trilobite anatomical structures on the order of 10 to 30 microns wide," she said. For comparison, a human hair is roughly 100 microns thick.

Though these specimens were first described in the late 1800s and others have used CT scans to examine them, this is the first study to use the technology to examine this part of the animal.

The researchers could see how blood would have filtered through chambers in these delicate structures, picking up oxygen along its way as it moved. They appear much the same as gills in modern marine arthropods like crabs and lobsters.

Comparing the specimens in pyrite to another trilobite species gave the team additional detail about how the filaments were arranged relative to one another, and to the legs.

Most trilobites scavenged the ocean floor, using spikes on their lower legs to catch and grind prey. Above those parts, on the upper branch of the limbs, were these additional structures that some believed were meant to help with swimming or digging.

"In the past, there was some debate about the purpose of these structures because the upper leg isn't a great location for breathing apparatus," Hopkins said. "You'd think it would be easy for those filaments to get clogged with sediment where they are. It's an open question why they evolved the structure in that place on their bodies."

The Hughes lab uses fossils to answer questions about how life developed in response to changes in Earth's atmosphere. Roughly 540 million years ago, there was an explosive diversification in the variety and complexity of animals living in the oceans.

"We've known theoretically this change must have been related to a rise in oxygen, since these animals require its presence. But we have had very little ability to measure that," Hughes said. "Which makes findings like these all the more exciting."

INFORMATION:

March 31, 2021 - The United States is facing a persistent and worsening shortage of physicians specializing in preventive medicine, reports a study in the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

"The number of preventive medicine physicians is not likely to match population needs in the United States in the near term and beyond," according to the new research by Thomas Ricketts, Ph.D., MPH, and colleagues of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The study appears ...

DETROIT (March 31, 2021) - In a study that looked at racial differences in outcomes of COVID-19 patients admitted to the intensive care unit, researchers at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit found that patients of color had a lower 28-day mortality than white patients.

Race, however, was not a factor in overall hospital mortality, length of stay in the ICU or in the rate of patients placed on mechanical ventilation, researchers said.

The findings, published in Critical Care Medicine, are believed to be one of the first in the United States to study racial differences and outcomes specific to patients hospitalized ...

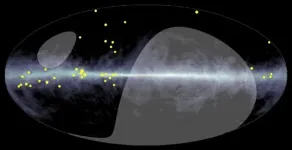

An enormous telescope complex in Tibet has captured the first evidence of ultrahigh-energy gamma rays spread across the Milky Way. The findings offer proof that undetected starry accelerators churn out cosmic rays, which have floated around our galaxy for millions of years. The research is to be published in the journal Physical Review Letters on Monday, April 5.

"We found 23 ultrahigh-energy cosmic gamma rays along the Milky Way," said Kazumasa Kawata, a coauthor from the University of Tokyo. "The highest energy among them amounts to a world record: nearly one petaelectron volt."

That's three ...

DURHAM, N.H.-- As the Biden administration announces a plan to expand the development of offshore wind energy development (OWD) along the East Coast, research from the University of New Hampshire shows significant support from an unlikely group, coastal recreation visitors. From boat enthusiasts to anglers, researchers found surprisingly widespread support with close to 77% of coastal recreation visitors supporting potential OWD along the N.H. Seacoast.

"This study takes a closer look at the lingering assumption that offshore wind in the United States might hurt coastal recreation ...

The first imaging of substantial freshwater plumes west of Hawai'i Island may help water planners to optimize sustainable yields and aquifer storage calculations. University of Hawai'i at Mānoa researchers demonstrated a new method to detect freshwater plumes between the seafloor and ocean surface in a study recently published in Geophysical Research Letters.

The research, supported by the Hawai'i EPSCoR 'Ike Wai project, is the first to demonstrate that surface-towed marine controlled-source electromagnetic (CSEM) imaging can be used to map oceanic freshwater plumes in high-resolution. It is an extension of the groundbreaking discovery of freshwater beneath the seafloor in 2020. Both are important findings in a world facing climate change, where ...

LOWELL, Mass. - Researchers studying mercury gas in the atmosphere with the aim of reducing the pollutant worldwide have determined a vast amount of the toxic element is absorbed by plants, leading it to deposit into soils.

Hundreds of tons of mercury each year are emitted into the atmosphere as a gas by burning coal, mining and other industrial and natural processes. These emissions are absorbed by plants in a process similar to how they take up carbon dioxide. When the plants shed leaves or die, the mercury is transferred to soils where large amounts also make their way into watersheds, threatening wildlife and people who eat contaminated fish.

Exposure to high levels of mercury over long ...

BRAZZAVILLE, Republic of Congo (March 31, 2021) - Researchers with the Wildlife Conservation Society's (WCS) Congo Program and the Nouabalé-Ndoki Foundation found that female putty-nosed monkeys (Cercopithecus nictitans) use males as "hired guns" to defend from predators such as leopards.

Publishing their results in the journal Royal Society Open Science, the team discovered that female monkeys use alarm calls to recruit males to defend them from predators. The researchers conducted the study among 19 different groups of wild putty-nosed monkeys, a type of forest guenon, in Mbeli Bai, a study area within the forests in Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park, Northern Republic of Congo.

The results promote the idea that females' general alarm requires males to assess the nature ...

(Denver, Colo., -- March 31, 2021)- A new Molecular Database Project initiated by the International Association for the Study of Lung (IASLC) will accelerate the understanding of lung cancer biology, clinical care and care delivery on a global scale and will improve the prognosis and optimal treatment of lung cancer across time and space, according to an editorial in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology, an official journal of the IASLC. The editorial can be viewed here: https://www.jto.org/article/S1556-0864(21)01781-0/fulltext.

In the editorial, the IASLC Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee's Molecular Sub-Committee, and committee members, emphasized that there is great opportunity, with the emergence of molecular biomarkers of disease behavior, to improve ...

Viruses lurk in the grey area between the living and the nonliving, according to scientists. Like living things, they replicate but they don't do it on their own. The HIV-1 virus, like all viruses, needs to hijack a host cell through infection in order to make copies of itself.

Supercomputer simulations supported by the National Science Foundation-funded Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) have helped uncover the mechanism for how the HIV-1 virus imports into its core the nucleotides it needs to fuel DNA synthesis, a key step in its replication. It's the first example ...

The qubit is the building block of quantum computing, analogous to the bit in classical computers. To perform error-free calculations, quantum computers of the future are likely to need at least millions of qubits. The latest study, published in the journal PRX Quantum, suggests that these computers could be made with industrial-grade silicon chips using existing manufacturing processes, instead of adopting new manufacturing processes or even newly discovered particles.

For the study, researchers were able to isolate and measure the quantum state of a single electron (the qubit) in a silicon transistor manufactured using a 'CMOS' technology similar to that used to make chips in computer processors.

Furthermore, the spin of the electron was found to remain stable for a period of up ...