How do our facial expressions influence how we see others' pain?

A new study indicates that suppressing our facial expressions when seeing others in pain may reduce how bad we feel, but not how much we feel their pain.

2021-04-01

(Press-News.org) How do our facial expressions in response to seeing others in pain influence how we see and feel their pain? There are many situations where it may be helpful to suppress our emotional responses to the pain of others. For example, doctors are trained to regulate their emotional responses to the pain of their patients, which may help them to avoid exhausting their own cognitive and emotional resources. Understanding whether suppressing our own facial expressions in response to other's pain reduces our ability to empathize with them has important implications for a variety of social relationships including those between doctors and patients, parents and children, and police officers and members of the community.

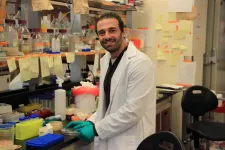

In a new study, titled "Expressive suppression to pain in others reduces negative emotion but not vicarious pain in the observer" and published in the journal Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, the authors sought to address this question. The study was authored by recent University of Miami Psychology Ph.D. graduate Steven Anderson and his advisor Elizabeth Losin, director of the Social and Cultural Neuroscience Laboratory at the University of Miami, in collaboration with Shihui Han and Wenxin Li at Peking University in Beijing, China.

The study used brain imaging to test the effects of suppressing one's facial responses to others in pain on patterns of brain activity, or neural signatures, related to two different aspects of pain empathy: negative emotions and vicarious pain. These previously developed neural signatures were the Picture Induced Negative Emotion Signature (PINES; Chang et al. 2015) and a neural signature of facial expression induced vicarious pain (FEIVPS; Zhou et al., 2020).

In a sample of 60 healthy individuals scanned in the U.S. and China, the researchers found that seeing faces displaying facial expressions of pain increased neural representations of both negative emotion (as measured by the PINES) and vicarious pain (as measured by the FEIVPS). Interestingly, however, suppressing facial expressions when viewing others in pain only reduced neural representations of negative emotion and did not influence vicarious pain.

In order to understand the meaning of these brain changes, the authors next compared them to participants' responses to questionnaires related to pain empathy. They found that those participants with higher brain responses related to negative emotion reported finding the pained faces more unpleasant and also reported taking others' perspectives more often in their daily lives. In addition, the authors found that participants who reported more frequently suppressing their facial expressions in everyday life also reported lower levels of empathy for others in general.

Importantly, the authors found that their results were not influenced by participants' gender or nationality, and similar effects of expressive suppression were observed in response to emotionally negative pictures in the scanner.

"As an emotion regulation strategy, expressive suppression is typically associated with negative social, cognitive, and emotional consequences," said Anderson. "Our study extends this work by suggesting that a potential negative consequence of suppressing your facial responses to others in pain may be to reduce your emotional empathy for them."

However, Anderson noted that the effects of expressive suppression may depend on the social context. "Our finding that expressive suppression reduced neural representations of negative emotion--but not vicarious pain--suggests that inhibiting facial expressivity may actually be useful in certain contexts. For example, by inhibiting their facial expressions, physicians may be able to reduce some of the negative emotions from seeing their patients in pain without reducing their ability to feel their patients' pain."

Anderson noted that future studies using physician and patient samples are needed to explore the effects of expressive suppression in clinical settings.

"Overall, this study highlights the utility of neuroimaging to examine neural processes that may be difficult to study in the real world," said Losin. "Shedding light on the basic neural mechanisms of the effect of emotion regulation on pain empathy can then inform future studies in more applied medical settings."

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-01

Mount Sinai Researchers Find "Removal of AKAP11 Protein by Autophagy as a key to Fuel Mitochondrial Metabolism and Tumor Cell Growth through activating protein kinase A (PKA) (Patent pending)"

Corresponding Author: Zhenyu Yue, PhD, Professor of Neurology, Aidekman Family Professorship, Director of Basic and Translational Research in Movement Disorders, Friedman Brain Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Bottom Line: We uncovered a mechanism that tumor cells exploit selective autophagy for metabolic reprogramming that benefits tumor cell growth and offers resistance to glucose deprivation. Our study suggests that AKAP220-mediated autophagy as a novel therapeutic target for specific cancer treatment.

Results: Autophagy is a lysosome degradation pathway that is cytoprotective ...

2021-04-01

How plants will fare as carbon dioxide levels continue to rise is a tricky problem and, researchers say, especially vexing in the tropics. Some aspects of plants' survival may get easier, some parts will get harder, and there will be species winners and losers. The resulting shifts in vegetation will help determine the future direction of climate change.

To explore the question, a study led by the University of Washington looked at how tropical forests, which absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide, might adjust as CO2 continues to climb. Their results show ...

2021-04-01

Chestnut Hill, MA (4/1/2021) - A gender gap in negotiation emerges as early as age eight, a finding that sheds new light on the wage gap women face in the workforce, according to new research from Boston College's Cooperation Lab, lead by Associate Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience Katherine McAuliffe.

The study of 240 boys and girls between ages four and nine, published recently in the journal Psychological Science, found the gap appears when girls who participated in the study were asked to negotiate with a male evaluator, a finding that mirrors the dynamics of the negotiation gap that persists between ...

2021-04-01

Statement Highlights:

Two-thirds of people with heart disease are ages 60 and older.

People who have had a heart attack or stroke are 20 times more likely to have additional cardiac events compared to people without heart disease.

Lifestyle modifications and medication adherence are key strategies to address heart disease.

Mobile health technology, which incorporates apps, devices, texting and phone calls, can inform and monitor older adults to support lifestyle modifications.

DALLAS, April 1, 2021 -- Mobile health technology can be beneficial in encouraging lifestyle behavior changes and medication adherence among adults ages 60 and older with existing heart disease, yet more research is needed to determine what methods are the most effective, according to a new scientific statement ...

2021-04-01

New research, led by scientists at the University of Nottingham, suggests that the environment in which men live may affect their reproductive health.

The research, published in Scientific Reports, looked at the effects of geographical location on polluting chemicals found in dog testes, some of which are known to affect reproductive health. The unique research focused on dogs because, as a popular pet, they share the same environment as people and are effectively exposed to the same household chemicals as their owners.

The team also looked for signs of abnormalities ...

2021-04-01

It is well known that climate-induced sea level rise is a major threat. New research has found that previous ice loss events could have caused sea-level rise at rates of around 3.6 metres per century, offering vital clues as to what lies ahead should climate change continue unabated.

A team of scientists, led by researchers from Durham University, used geological records of past sea levels to shed light on the ice sheets responsible for a rapid pulse of sea-level rise in Earth's recent past.

Geological records tell us that, at the end of the last ice age around 14,600 years ago, sea levels rose at ten times the current rate due to Meltwater Pulse 1A (MWP-1A); a 500 year, ~18 metre sea-level rise event.

Until now, the scientific community has not ...

2021-04-01

Genome sequencing of thousands of SARS-CoV-2 samples shows that surges of COVID-19 cases are driven by the appearance of new coronavirus variants, according to new research from the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of California, Davis published April 1 in Scientific Reports.

"As variants emerge, you're going to get new outbreaks," said Bart Weimer, professor of population health and reproduction at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. The merger of classical epidemiology with genomics provides a tool public health authorities could use to predict the course of pandemics, whether of coronavirus, influenza or some new pathogen.

Although it has just 15 genes, SARS-CoV-2 is constantly mutating. Most of these changes make very little ...

2021-04-01

Hamilton, ON (April 1, 2021) - People living with the often-debilitating effects of Crohn's disease may finally gain some relief, thanks to ground-breaking research led by McMaster University.

McMaster investigator Brian Coombes said his team identified a strain of adherent-invasive E-coli (AIEC) that is strongly implicated in the condition and is often found in the intestines of people with Crohn's disease.

"If you examine the gut lining of patients with Crohn's disease, you will find that around 70 to 80 per cent of them test positive for AIEC bacteria, but one of the things we don't understand is why," said Coombes, professor and chair of the Department of Biochemistry and ...

2021-04-01

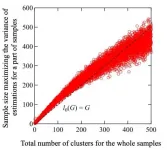

Ishikawa, Japan - Any high-performance computing should be able to handle a vast amount of data in a short amount of time -- an important aspect on which entire fields (data science, Big Data) are based. Usually, the first step to managing a large amount of data is to either classify it based on well-defined attributes or--as is typical in machine learning--"cluster" them into groups such that data points in the same group are more similar to one another than to those in another group. However, for an extremely large dataset, which can have trillions of sample points, it is tedious to even group data points into a single cluster without huge memory requirements.

"The problem can be formulated as follows: Suppose we have a clustering tool that ...

2021-04-01

The kangaskhan, Australia's only species of endemic Pokemon in Pokemon Go, is commonly poached within its natural habitat by Pokemon trainers for use in fighting contests

Researchers used several species distribution modeling algorithms to predict how climate change, on top of the already existing human-induced pressures, would impact the distribution of the kangaskhan in the future

In addition to this, they found a way to measure how biased commonly used species distribution models are, and found that some models are so biased that their results weren't influenced by the data at all

The ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] How do our facial expressions influence how we see others' pain?

A new study indicates that suppressing our facial expressions when seeing others in pain may reduce how bad we feel, but not how much we feel their pain.