(Press-News.org) Multilingual people have trained their brains to learn languages, making it easier to acquire more new languages after mastering a second or third. In addition to demystifying the seemingly herculean genius of multilinguals, researchers say these results provide some of the first neuroscientific evidence that language skills are additive, a theory known as the cumulative?enhancement model of language acquisition.

"The traditional idea is, if you understand bilinguals, you can use those same details to understand multilinguals. We rigorously checked that possibility with this research and saw multilinguals' language acquisition skills are not equivalent, but superior to those of bilinguals," said Professor Kuniyoshi L. Sakai from the University of Tokyo, an expert in the neuroscience of language and last author of the research study recently published in Scientific Reports. This joint research project includes collaboration with Professor Suzanne Flynn from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), a specialist in linguistics and multilanguage acquisition, who first proposed the cumulative?enhancement model.

Neuroscientists measured brain activity while 21 bilingual and 28 multilingual adult volunteers tried to identify words and sentences in Kazakh, a language brand new to them.

All participants were native speakers of Japanese whose second language was English. Most of the multilingual participants had learned Spanish as a third language, but others had learned Chinese, Korean, Russian or German. Some knew up to five languages.

Fluency in multiple languages requires command of different sounds, vocabularies, sentence structures and grammar rules. Sentences in English and Spanish are usually structured with the noun or verb at the start of a phrase, but Japanese and Kazakh consistently place nouns or verbs at the end of a phrase. English, Spanish and Kazakh grammars require subject-verb agreement (she walks, they walk), but Japanese grammar does not.

Instead of grammar drills or conversation skills in a classroom, researchers simulated a more natural language learning environment where volunteers had to figure out the fundamentals of a new language purely by listening. Volunteers listened to recordings of individual Kazakh words or short sentences including those words while watching a screen with plus or minus symbols to signal if the sentence was grammatically correct or not. Volunteers were given a series of four increasingly difficult listening tests while researchers measured their brain activity using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

In the simplest test, volunteers had to determine if they were hearing a word from the earlier learning session or if it was a grammatically different version of the same word; for example: run/ran or take/takes. In the next test levels, volunteers listened to example sentences and were asked if the sentences were grammatically correct and to decipher sentence structures by identifying noun-verb pairs. For example, "We understood that John thought," is translated in Kazakh as "Biz John oyladï dep tu?sindik." The sentence would be grammatically incorrect if volunteers heard tu?sindi instead of tu?sindik. The correct noun-verb pairs are we understood (Biz tu?sindik) and John thought (John oyladï).

Volunteers could retake the learning session and repeat the test an unlimited number of times until they passed and progressed to the next level of difficulty.

Multilingual participants who were more fluent in their second and third languages were able to pass the Kazakh tests with fewer repeated learning sessions than their less-fluent multilingual peers. More-fluent multilinguals also became faster at choosing an answer as they progressed from the third to fourth test level, a sign of increased confidence and that knowledge acquired during easier tests was successfully transferred to higher levels.

"For multilinguals, in Kazakh, the pattern of brain activation is similar to that for bilinguals, but the activation is much more sensitive, and much faster," said Sakai.

The pattern of brain activation in bilingual and multilingual volunteers fits current understanding of how the brain understands language, specifically that portions of the left frontal lobe become more active when understanding both the content and meaning of a sentence. When learning a second language, it is normal for the corresponding areas on the right side of the brain to become active and assist in efforts to understand.

Multilingual volunteers had no detectable right-side activation during the initial, simple Kazakh grammar test level, but brain scans showed strong activity in those assisting areas of bilingual volunteers' brains.

Researchers also detected differences in the basal ganglia, often considered a more fundamental area of the brain. Bilingual volunteers' basal ganglia had low levels of activation that spiked as they progressed through the test and then returned to a low level at the start of the next test. Multilingual volunteers began the first test level with similarly low basal ganglia activity that spiked and then remained high throughout the subsequent test levels.

The UTokyo-MIT research team says this activation pattern in the basal ganglia shows that multilingual people can make generalizations and build on prior knowledge, rather than approach each new grammar rule as a separate idea to understand from scratch.

Multilingual people have an advantage over those fluent in only two languages

UTokyo-MIT study measures brain activity while learning basic sounds, grammar rules of unfamiliar language

2021-04-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

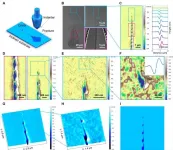

cientists observe role of cavitation in glass fracturing

2021-04-01

Glassy materials play an integral role in the modern world, but inherent brittleness has long been the Achilles' heel that severely limits their usefulness. Due to the disordered amorphous structure of glassy materials, many mysteries remain. These include the fracture mechanisms of traditional glasses, such as silicate glasses, as well as the origin of the intriguing patterned fracture morphologies of metallic glasses.

Cavitation has been widely assumed to be the underlying mechanism governing the fracture of metallic glasses, as well as other glassy systems. Up until now, however, scientists have been unable to directly observe the cavitation behavior of fractures, despite their intensive ...

Large study identified new genetic link to male infertility

2021-04-01

The findings published in eLife show that men with this unstable subtype of the Y chromosome have a significantly increased risk of genomic rearrangements. These rearrangements affect the sperm production process (spermatogenesis) and consequently, these men can be up to nine times more likely to have fertility issues. Molecular diagnostics of this genetic variant could help identify those at higher risk in their early adulthood, giving them the chance to make decisions about future family planning early on. Currently, the exact cause of infertility ...

Gut microbiota in cesarean-born babies catches up

2021-04-01

Infants born by cesarean section have a relatively meager array of bacteria in the gut. But by the age of three to five years they are broadly in line with their peers. This is shown by a study that also shows that it takes a remarkably long time for the mature intestinal microbiota to get established.

Fredrik Bäckhed, Professor of Molecular Medicine at Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, has been heading this research. The study, conducted in collaboration with Halland County Hospital in Halmstad, is now published in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

Professor Bäckhed and his group have previously demonstrated that the composition of children's intestinal microbiota is affected by their mode of delivery and ...

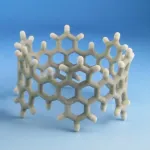

Researchers develop third and final 'made-to-order' nanotube synthesis technique

2021-04-01

The current method of manufacturing carbon nanotubes--in essence rolled up sheets of graphene--is unable to allow complete control over their diameter, length and type. This problem has recently been solved for two of the three different types of nanotubes, but the third type, known as 'zigzag' nanotubes, had remained out of reach. Researchers with Japan's National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) have now figured out how to synthesize the zigzag variety.

Their method is described in the journal Nature Chemistry, published on January 25.

Thanks to carbon's unique capacity to combine ...

Keeping it fresh: New AI-based strategy can assess the freshness of beef samples

2021-04-01

Although beef is one of the most consumed foods around the world, eating it when it's past its prime is not only unsavory, but also poses some serious health risks. Unfortunately, available methods to check for beef freshness have various disadvantages that keep them from being useful to the public. For example, chemical analysis or microbial population evaluations take too much time and require the skills of a professional. On the other hand, non-destructive approaches based on near-infrared spectroscopy require expensive and sophisticated equipment. Could artificial intelligence be the key to a more cost-effective way to assess the freshness of beef?

At Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology (GIST), Korea, a team of scientists led by Associate Processors Kyoobin Lee and ...

Plasma jets stabilize water to splash less

2021-04-01

A study by KAIST researchers revealed that an ionized gas jet blowing onto water, also known as a 'plasma jet', produces a more stable interaction with the water's surface compared to a neutral gas jet. This finding reported in the April 1 issue of Nature will help improve the scientific understanding of plasma-liquid interactions and their practical applications in a wide range of industrial fields in which fluid control technology is used, including biomedical engineering, chemical production, and agriculture and food engineering.

Gas jets can create dimple-like depressions in liquid surfaces, and this phenomenon is familiar to anyone who has seen the cavity produced by blowing air through a straw ...

How do our facial expressions influence how we see others' pain?

2021-04-01

How do our facial expressions in response to seeing others in pain influence how we see and feel their pain? There are many situations where it may be helpful to suppress our emotional responses to the pain of others. For example, doctors are trained to regulate their emotional responses to the pain of their patients, which may help them to avoid exhausting their own cognitive and emotional resources. Understanding whether suppressing our own facial expressions in response to other's pain reduces our ability to empathize with them has important implications for a variety ...

Mount Sinai researchers find novel therapeutic target for specific cancer treatment

2021-04-01

Mount Sinai Researchers Find "Removal of AKAP11 Protein by Autophagy as a key to Fuel Mitochondrial Metabolism and Tumor Cell Growth through activating protein kinase A (PKA) (Patent pending)"

Corresponding Author: Zhenyu Yue, PhD, Professor of Neurology, Aidekman Family Professorship, Director of Basic and Translational Research in Movement Disorders, Friedman Brain Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Bottom Line: We uncovered a mechanism that tumor cells exploit selective autophagy for metabolic reprogramming that benefits tumor cell growth and offers resistance to glucose deprivation. Our study suggests that AKAP220-mediated autophagy as a novel therapeutic target for specific cancer treatment.

Results: Autophagy is a lysosome degradation pathway that is cytoprotective ...

Thicker-leaved tropical plants may flourish as CO2 rises, which could be good for climate

2021-04-01

How plants will fare as carbon dioxide levels continue to rise is a tricky problem and, researchers say, especially vexing in the tropics. Some aspects of plants' survival may get easier, some parts will get harder, and there will be species winners and losers. The resulting shifts in vegetation will help determine the future direction of climate change.

To explore the question, a study led by the University of Washington looked at how tropical forests, which absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide, might adjust as CO2 continues to climb. Their results show ...

A gender gap in negotiation emerges between boys and girls as early as age eight

2021-04-01

Chestnut Hill, MA (4/1/2021) - A gender gap in negotiation emerges as early as age eight, a finding that sheds new light on the wage gap women face in the workforce, according to new research from Boston College's Cooperation Lab, lead by Associate Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience Katherine McAuliffe.

The study of 240 boys and girls between ages four and nine, published recently in the journal Psychological Science, found the gap appears when girls who participated in the study were asked to negotiate with a male evaluator, a finding that mirrors the dynamics of the negotiation gap that persists between ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

App aids substance use recovery in vulnerable populations

[Press-News.org] Multilingual people have an advantage over those fluent in only two languagesUTokyo-MIT study measures brain activity while learning basic sounds, grammar rules of unfamiliar language