(Press-News.org) In some cancers, including leukemia in children and adolescents, obesity can negatively affect survival outcomes. Obese young people with leukemia are 50% more likely to relapse after treatment than their lean counterparts.

Now, a study led by researchers at UCLA and Children's Hospital Los Angeles has shown that a combination of modest dietary changes and exercise can dramatically improve survival outcomes for those with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the most common childhood cancer.

The researchers found that patients who reduced their calorie intake by 10% or more and adopted a moderate exercise program immediately after their diagnosis had, on average, 70% less chance of having lingering leukemia cells after a month of chemotherapy than those not on the diet-and-exercise regimen.

Lingering cancer cells in the bone marrow, which are more likely to be found in overweight individuals, are associated with worse survival and a higher risk of relapse, often leading to more intense treatments like bone marrow transplants and immunotherapy.

"We tested a very mild diet because this was our first time trying it, and the first month of treatment is already so difficult for patients and families," said senior author Dr. Steven Mittelman, chief of pediatric endocrinology at UCLA Mattel Children's Hospital and a member of the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. "But even with these mild changes in diet and exercise, the intervention was extremely effective in reducing the chance of having detectable leukemia in the bone marrow."

As part of the clinical trial, which took place at Children's Hospital Los Angeles, researchers worked with registered dieticians and physical therapists to create personalized 28-day interventions for 40 young people between the ages of 10 and 21 who were newly diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

The intervention was designed to cut participants' calorie intake by a minimum of 10% in order to reduce both fat gain and lean muscle loss. The physical activity component included a target level of 200 minutes per week of moderate exercise.

The results, published in the American Society of Hematology's journal Blood Advances, showed a decrease in fat gain among those who were overweight and obese, as well as an improved insulin sensitivity and an increase in the beneficial hormone adiponectin, which is involved in regulating glucose and breaking down fatty acids. Most importantly, the researchers found a 70% decrease in the chance of having lingering leukemia cells in the bone marrow -- known medically as minimal residual disease -- when compared with a historical control group.

"We hoped the intervention would improve outcomes, but we had no idea it would be so effective," Mittelman said. "We can't really add more toxic chemotherapies to the intense initial treatment phase, but this is an intervention that likely has no negative side effects. In fact, we hope it may even reduce toxicities caused by chemotherapy."

"This is the first trial to test a diet-and-exercise intervention to improve treatment outcomes from a childhood cancer," said principal investigator and lead author Dr. Etan Orgel, Director of the Medical Supportive Care Service in the Cancer and Blood Disease Institute at Children's Hospital Los Angeles. "This is an exciting proof-of-concept, which may have great implications for other cancers as well."

Next steps include further testing of the approach in a multicenter randomized trial, which will be launched later this year, the researchers said.

INFORMATION:

Other authors include Jiyoon Kim and Gang Li of UCLA; Celia Framson, Rubi Buxton, David Freyer and Matthew Oberley of Children's Hospital Los Angeles; Weili Sun of City of Hope; Jonathan Tucci of Vanderbilt University Medical Center; and Christina Dieli-Conwright of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

The study was supported by the Gabrielle Angel Foundation for Cancer Research, the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute.

For years, research to pin down the underlying cause of Alzheimer's Disease has been focused on plaque found to be building up in the brain in AD patients. But treatments targeted at breaking down that buildup have been ineffective in restoring cognitive function, suggesting that the buildup may be a side effect of AD and not the cause itself.

A new study led by a team of Brigham Young University researchers finds novel cellular-level support for an alternate theory that is growing in strength: Alzheimer's could actually be a result of metabolic dysfunction in the brain. In other words, there is growing evidence that diet and lifestyle are at the ...

Los Angeles (April 1, 2021) -- Overweight children and adolescents receiving chemotherapy for treatment of leukemia are less successful battling the disease compared to their lean peers. Now, research conducted at the END ...

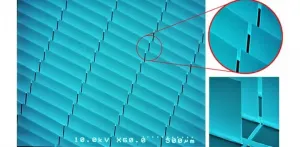

Buildings are responsible for 40 percent of primary energy consumption and 36 percent of total CO2 emissions. And, as we know, CO2 emissions trigger global warming, sea level rise, and profound changes in ocean ecosystems. Substituting the inefficient glazing areas of buildings with energy efficient smart glazing windows has great potential to decrease energy consumption for lighting and temperature control.

Harmut Hillmer et al. of the University of Kassel in Germany demonstrate that potential in "MOEMS micromirror arrays in smart windows for daylight steering," a paper published recently in the inaugural issue of the Journal of Optical Microsystems.

"Our smart glazing ...

A highly contagious SARS-CoV-2 variant was unknowingly spreading for months in the United States by October 2020, according to a new study from researchers with The University of Texas at Austin COVID-19 Modeling Consortium. Scientists first discovered it in early December in the United Kingdom, where the highly contagious and more lethal variant is thought to have originated. The journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, which has published an early-release version of the study, provides evidence that the coronavirus variant B117 (501Y) had spread across the globe undetected for months when scientists discovered it.

"By the time we learned about the U.K. variant ...

A possible explanation for why many cancer drugs that kill tumor cells in mouse models won't work in human trials has been found by researchers with The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) School of Biomedical Informatics and McGovern Medical School.

The research was published today in Nature Communications.

In the study, investigators reported the extensive presence of mouse viruses in patient-derived xenografts (PDX). PDX models are developed by implanting human tumor tissues in immune-deficient mice, and are commonly ...

Boulder, Colo., USA: The Geological Society of America regularly publishes

articles online ahead of print. For March, GSA Bulletin topics

include multiple articles about the dynamics of China and Tibet; the ups

and downs of the Missouri River; the Los Rastros Formation, Argentina; the

Olympic Mountains of Washington State; methane seep deposits; meandering

rivers; and the northwest Hawaiian Ridge. You can find these articles at

https://bulletin.geoscienceworld.org/content/early/recent

.

Transition from a passive to active continental ...

We've all heard the adage, "If at first you don't succeed, try, try again," but new research from Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh finds that it isn't all about repetition. Rather, internal states like engagement can also have an impact on learning.

The collaborative research, published in Nature Neuroscience, examined how changes in internal states, such as arousal, attention, motivation, and engagement can affect the learning process using brain-computer interface (BCI) technology. Findings suggest that changes in internal states can systematically influence how behavior improves with learning, thus paving the way ...

A study reported in the journal Current Biology on April 1 has both good news and bad news for the future of African elephants. While about 18 million square kilometers of Africa--an area bigger than the whole of Russia--still has suitable habitat for elephants, the actual range of African elephants has shrunk to just 17%of what it could be due to human pressure and the killing of elephants for ivory.

"We looked at every square kilometer of the continent," says lead author Jake Wall of the Mara Elephant Project in Kenya. "We found that 62% of those 29.2 million ...

Tokyo, Japan - Type I Diabetes Mellitus (T1D) is an autoimmune disorder leading to permanent loss of insulin-producing beta-cells in the pancreas. In a new study, researchers from The University of Tokyo developed a novel device for the long-term transplantation of iPSC-derived human pancreatic beta-cells.

T1D develops when autoimmune antibodies destroy pancreatic beta-cells that are responsible for the production of insulin. Insulin regulates blood glucose levels, and in the absence of it high levels of blood glucose slowly damage the kidneys, eyes and peripheral ...

A new study shows that the similarly smooth, nearly hairless skin of whales and hippopotamuses evolved independently. The work suggests that their last common ancestor was likely a land-dwelling mammal, uprooting current thinking that the skin came fine-tuned for life in the water from a shared amphibious ancestor. The study is published today in the journal Current Biology and was led by researchers at the American Museum of Natural History; University of California, Irvine; University of California, Riverside; Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics; and the LOEWE-Centre for Translational Biodiversity Genomics (Germany).

"How mammals left terra firma and became fully aquatic is one of the most fascinating evolutionary ...