(Press-News.org) Buildings are responsible for 40 percent of primary energy consumption and 36 percent of total CO2 emissions. And, as we know, CO2 emissions trigger global warming, sea level rise, and profound changes in ocean ecosystems. Substituting the inefficient glazing areas of buildings with energy efficient smart glazing windows has great potential to decrease energy consumption for lighting and temperature control.

Harmut Hillmer et al. of the University of Kassel in Germany demonstrate that potential in "MOEMS micromirror arrays in smart windows for daylight steering," a paper published recently in the inaugural issue of the Journal of Optical Microsystems.

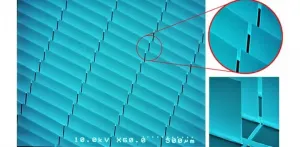

"Our smart glazing is based on millions of micromirrors, invisible to the bare eye, and reflects incoming sunlight according to user actions, sun positions, daytime, and seasons, providing a personalized light steering inside the building," Hillmer said.

The micromirror array is invulnerable to wind, window cleaning, or any weather conditions because it is located in the space between the windowpanes filled with noble gas such as argon or krypton. The glazing provides free solar heat in winter and overheating prevention in summer, and it enables healthy natural daylight, huge energy savings (up to 35 percent), massive CO2 reduction (up to 30 percent), and a reduction of 10 percent steel and concrete in high-rise buildings.

Apart from the energy problem, artificial lighting also has consequences for health and well-being. Various studies have linked artificial lighting to lack of concentration, high susceptibility to illness, disturbed biorhythms, and sleeplessness. Smart glass can reduce reliance on artificial lighting by optimizing natural daylight in a room.

Current state-of-the-art smart glazings are currently optimized either for winter or for summer-and not able to ensure energy-saving performance year-round. There has been a need for a smart and automatic technology that can react to local climate (daytime, season), uses available sunlight, regulates light and temperature, and saves substantial energy.

The researchers' MEMS micromirror arrays are integrated inside insulation glazing and are operated by an electronic control system. The orientation of mirrors is controlled by the voltage between respective electrodes. Motion sensors in the room detect the number, position, and movement of users in the room.

The results include much higher actuation speed in the sub-ms range, 40-times lower power consumption than electrochromic or liquid crystal concepts, reflection instead of absorption, and color neutrality. Rapid aging tests of the micromirror structure were performed to study reliability and revealed sustainability, robustness, and long lifetimes of the micromirror arrays.

And with positive results like that, the benefits of this smart glass are crystal clear.

INFORMATION:

Read the open access research article: Harmut Hillmer, Mustaqim Siddi Que Iskhandar, Muhammad Kamrul Hasan, Sapida Akhundzada, Basim Al-Qargholi, Andreas Tatzel, "MOEMS micromirror arrays in smart windows for daylight steering," J. Optical Microsyst. 1(1), 014502 (2021). DOI: 10.1117/1.JOM.1.1.014502

A highly contagious SARS-CoV-2 variant was unknowingly spreading for months in the United States by October 2020, according to a new study from researchers with The University of Texas at Austin COVID-19 Modeling Consortium. Scientists first discovered it in early December in the United Kingdom, where the highly contagious and more lethal variant is thought to have originated. The journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, which has published an early-release version of the study, provides evidence that the coronavirus variant B117 (501Y) had spread across the globe undetected for months when scientists discovered it.

"By the time we learned about the U.K. variant ...

A possible explanation for why many cancer drugs that kill tumor cells in mouse models won't work in human trials has been found by researchers with The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) School of Biomedical Informatics and McGovern Medical School.

The research was published today in Nature Communications.

In the study, investigators reported the extensive presence of mouse viruses in patient-derived xenografts (PDX). PDX models are developed by implanting human tumor tissues in immune-deficient mice, and are commonly ...

Boulder, Colo., USA: The Geological Society of America regularly publishes

articles online ahead of print. For March, GSA Bulletin topics

include multiple articles about the dynamics of China and Tibet; the ups

and downs of the Missouri River; the Los Rastros Formation, Argentina; the

Olympic Mountains of Washington State; methane seep deposits; meandering

rivers; and the northwest Hawaiian Ridge. You can find these articles at

https://bulletin.geoscienceworld.org/content/early/recent

.

Transition from a passive to active continental ...

We've all heard the adage, "If at first you don't succeed, try, try again," but new research from Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh finds that it isn't all about repetition. Rather, internal states like engagement can also have an impact on learning.

The collaborative research, published in Nature Neuroscience, examined how changes in internal states, such as arousal, attention, motivation, and engagement can affect the learning process using brain-computer interface (BCI) technology. Findings suggest that changes in internal states can systematically influence how behavior improves with learning, thus paving the way ...

A study reported in the journal Current Biology on April 1 has both good news and bad news for the future of African elephants. While about 18 million square kilometers of Africa--an area bigger than the whole of Russia--still has suitable habitat for elephants, the actual range of African elephants has shrunk to just 17%of what it could be due to human pressure and the killing of elephants for ivory.

"We looked at every square kilometer of the continent," says lead author Jake Wall of the Mara Elephant Project in Kenya. "We found that 62% of those 29.2 million ...

Tokyo, Japan - Type I Diabetes Mellitus (T1D) is an autoimmune disorder leading to permanent loss of insulin-producing beta-cells in the pancreas. In a new study, researchers from The University of Tokyo developed a novel device for the long-term transplantation of iPSC-derived human pancreatic beta-cells.

T1D develops when autoimmune antibodies destroy pancreatic beta-cells that are responsible for the production of insulin. Insulin regulates blood glucose levels, and in the absence of it high levels of blood glucose slowly damage the kidneys, eyes and peripheral ...

A new study shows that the similarly smooth, nearly hairless skin of whales and hippopotamuses evolved independently. The work suggests that their last common ancestor was likely a land-dwelling mammal, uprooting current thinking that the skin came fine-tuned for life in the water from a shared amphibious ancestor. The study is published today in the journal Current Biology and was led by researchers at the American Museum of Natural History; University of California, Irvine; University of California, Riverside; Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics; and the LOEWE-Centre for Translational Biodiversity Genomics (Germany).

"How mammals left terra firma and became fully aquatic is one of the most fascinating evolutionary ...

PHILADELPHIA -- (April 1, 2021 -- Scientists at The Wistar Institute identified a new mechanism of transcriptional control of cellular senescence that drives the release of inflammatory molecules that influence tumor development through altering the surrounding microenvironment. The study, published in Nature Cell Biology, reports that methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) and 14 (METTL14) proteins moonlight as transcriptional regulators that allow for establishment of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).

Cellular senescence is a stable state of growth arrest in which cells stop dividing but remain viable and produce an array of inflammatory and growth-promoting molecules collectively defined as SASP. These molecules account ...

The University of Maryland (UMD) has collaborated with Cornell University and Stanford University to quantify the man-made effects of climate change on global agricultural productivity growth for the first time. In a new study published in Nature Climate Change, researchers developed a robust model of weather effects on productivity, looking at productivity in both the presence and absence of climate change. Results indicate a 21% reduction in global agricultural productivity since 1961, which according to researchers is equivalent to completely losing the last 7 years ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Despite important agricultural advancements to feed the world in the last 60 years, a Cornell-led study shows that global farming productivity is 21% lower than it could have been without climate change. This is the equivalent of losing about seven years of farm productivity increases since the 1960s.

The future potential impacts of climate change on global crop production has been quantified in many scientific reports, but the historic influence of anthropogenic climate change on the agricultural sector had yet to be modeled.

Now, a new study provides these insights: "Anthropogenic Climate Change Has Slowed Global Agricultural Productivity ...