(Press-News.org) Aquaculture--the farming of fish, shellfish, and other aquatic animals for food--has reached unprecedented levels of growth in recent years, but largely without consideration of its impact on individual animals, finds a new analysis by a team of researchers.

"The scale of modern aquaculture is immense and still growing," says Becca Franks, a research scientist at New York University's Department of Environmental Studies and the lead author of the paper, which appears in the journal Science Advances. "Yet we know so little about the animals that we are putting into mass production, and the negative consequences of aquaculture's expansion on individual animals will just continue to accumulate."

The study is the first to systematically examine the scientific knowledge about animal welfare for the 408 aquatic animal species being farmed around the world--animals that include salmon, carp, and shrimp. The researchers found that specialized scientific studies about animal welfare--generally defined as an animal's ability to cope with its environment--were available for just 84 species. The remaining 324 species, which represent the majority of aquaculture production, had no information available.

Animal welfare legislation is not new, but in recent years, governments have adopted laws aimed at enhancing enforcement and extending animal protections.

With traditional fishing on the decline, aquaculture has been touted as both a solution to food insecurity and as a means to reduce pressure on species in seas and oceans. However, the growth of aquaculture, or aquafarming, hasn't diminished stress on wild populations. Meanwhile, as recently as 2018, 250 to 408 billion individual animals from more than 400 species were farmed in aquaculture--or about 20 times the number of species farmed in animal agriculture on land--according to the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization.

The expansion of aquaculture raises concerns that the industry is moving ahead without sufficient knowledge of the animal life it is growing. The absence of this information signals risk because its operations and decisions are not scientifically based, the researchers note, and can lead to poor living conditions and suffering for the individual animals involved.

To explore this matter, the team, which also included Jennifer Jacquet, an associate professor in NYU's Department of Environmental Studies, and Chris Ewell, an NYU undergraduate at the time of the study, sought to determine what research literature existed on the more than 400 species being farmed in 2018.

Their results showed that only 25 species, or about 7 percent of animals being farmed in aquaculture, had five or more publications on these animals' welfare. By contrast, 231 species had no welfare publications while 59 had only one to four such publications. The remaining 93 did not have species-level taxonomic information, meaning it lacked sufficiently detailed findings on these species.

"While the presence of animal welfare knowledge does not ensure well-being, the absence of such information is troubling," says Franks. "In sum, our research reveals that modern aquaculture poses unparalleled animal welfare threats in terms of the global scope and the number of individual animal lives affected."

The authors emphasize that some aquatic animal species, such as bivalves, which include oysters and clams, may present fewer welfare concerns to begin with and may be a more promising avenue for production.

"Although aquaculture has been around for thousands of years, its current expansion is unprecedented and is posing great risks, but, because it is so new, we can choose a different path forward," Franks says.

INFORMATION:

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abg0677

ANN ARBOR--We are made of stardust, the saying goes, and a pair of studies including University of Michigan research finds that may be more true than we previously thought.

The first study, led by U-M researcher END ...

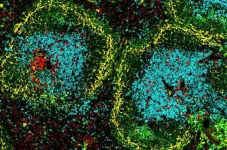

WEHI researchers have discovered a key differentiation process that provides an essential immune function in helping to control cancer and infectious diseases.

The research, published in Science Immunology, is the first to show a new factor - DC-SCRIPT - is required for the function a particular type of dendritic cell - called cDC1 - that is essential in controlling the immune response to infection.

Led by WEHI Professor Stephen Nutt, Dr Michael Chopin and Mr Shengbo Zhang, it defines the role for a new regulatory protein - DC-SCRIPT - in producing dendritic cells.

At a glance

WEHI researchers have uncovered a key step in the formation of a particular type of dendritic cell - called cDC1 - in controlling ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. -- If you walk with your spouse or partner on a regular basis, you might want to speed up. Or tell them to.

A new study by Purdue University nursing, health and kinesiology, and human development and family studies researchers shows that couples often decreased their speed when walking together. Speed further decreased if they were holding hands.

The study looked at walking times and gait speeds of 141 individuals from 72 couples. The participants ranged from age 25-79 and were in numerous settings, including clear or obstacle-filled pathways, walking together, walking together holding hands and walking individually.

"In our study, we focused on couples because partners in committed relationships often provide essential support ...

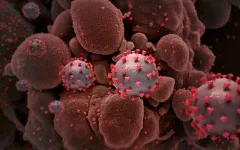

Wearing a face mask can protect yourself and others from Covid-19, but the type of material and how many fabric layers used can significantly affect exposure risk, finds a study from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

The study measured the filtration efficiency of submicron particles passing through a variety of different materials. For comparison, a human hair is about 50 microns in diameter while 1 millimeter is 1,000 microns in size.

"A submicron particle can stay in the air for hours and days, depending on the ventilation, so if you have a room that is not ventilated or poorly ventilated then these small particles can stay there for a very long period of time," said Nga Lee (Sally) Ng, associate professor and Tanner Faculty Fellow in the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering ...

New research led by investigators from Boston Medical Center and Grady Memorial Hospital demonstrates the significant decline in hospitalizations for neurological emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. The rate of Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) - bleeding in the space between the brain and the tissue covering the brain - hospitalizations declined 22.5 percent during the study period, which is consistent with the other reported decreases in emergencies such as stroke or heart attacks.

Published in Stroke & Vascular Neurology, the study compares subarachnoid hemorrhage hospital admissions for the months following throughout the initial COVID surge, in hospitals that bore ...

In a new study, researchers identify three clinical COVID-19 phenotypes, reflecting patient populations with different comorbidities, complications and clinical outcomes. The three phenotypes are described in a paper published this week in the open-access journal PLOS ONE 1st authors Elizabeth Lusczek and Nicholas Ingraham of University of Minnesota Medical School, US, and colleagues.

COVID-19 has infected more than 18 million people and led to more than 700,000 deaths around the world. Emergency department presentation varies widely, suggesting that distinct clinical phenotypes exist and, importantly, that these distinct phenotypic presentations may respond differently ...

HOUSTON - (April 2, 2021) - Understanding what drives food choices can help high-volume food service operations like universities reduce waste, according to a new study.

Researchers have concluded that food waste in places like university cafeterias is driven by how much people put on their plates, how familiar they are with what's on the menu and how much they like - or don't like - what they're served.

Food waste has been studied often in households, but not so often in institutional settings like university dining commons. What drives food choices in these "all-you-care-to-eat" facilities is different because diners don't perceive personal financial penalty if they leave food on their plates.

Published in the journal Foods, "Food Choice and Waste in University Dining Commons ...

A personalized tumor cell vaccine strategy targeting Myc oncogenes combined with checkpoint therapy creates an effective immune response that bypasses antigen selection and immune privilege, according to a pre-clinical study for neuroblastoma and melanoma. The neuroblastoma model showed a 75% cure with long-term survival, researchers at Children's National Hospital found.

Myc is a family of regulator genes and proto-oncogenes that help manage cell growth and differentiation in the body. When Myc mutates to an oncogene, it can promote cancer cell growth. The Myc oncogenes are ...

James McKerrow, MD, PhD, dean of the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at University of California San Diego, has long studied neglected tropical diseases -- chronic and disabling parasitic infections that primarily affect poor and underserved communities in developing nations. They're called "neglected" because there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies to develop therapies for them.

One of these neglected diseases is Chagas disease, the leading cause of heart failure in Latin America, which is spread by "kissing bugs" carrying the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. These parasites produce an enzyme called cruzain that helps ...

A novel mechanism has been identified that might explain why a rare mutation is associated with familial Alzheimer's disease in a new study by investigators at the University of Chicago. The paper, published on April 2 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, characterizes a mutation located in a genetic region that was not previously thought be pathogenic, upending assumptions about what kinds of mutations can be associated with Alzheimer's Disease.

Alzheimer's, a neurodegenerative disease that currently affects more than 6 million Americans, has ...