(Press-News.org) "On a scale of one to 10, how much pain are you in?"

In a recent study published by the Journal of Pain, co-authored by Elizabeth Losin, assistant professor of psychology and director of the Social and Cultural Neuroscience lab at the University of Miami, researchers found that a patient's pain responses may be perceived differently by others based on their gender.

According to "Gender biases in estimation of others' pain," when male and female patients expressed the same amount of pain, observers viewed female patients' pain as less intense and more likely to benefit from psychotherapy versus medication as compared to men's pain, exposing a significant patient gender bias that could lead to disparities in treatments.

The study consisted of two experiments. In the first, 50 participants were asked to view various videos of male and female patients who suffered from shoulder pain performing a series of range of motion exercises using their injured and uninjured shoulders. Researchers pulled the videos from a database that contains videos of actual shoulder injury patients, each experiencing a range of different degrees of pain. The database included patients' self-reported level of discomfort when moving their shoulders.

According to Losin, the study likely provides results more applicable to patients in clinical settings compared to previous studies that used posed actors in their stimuli videos.

"One of the advantages of using these videos of patients who are actually experiencing pain from an injury is that we have the patients' ratings of their own pain," she explained. "We had a ground truth to work with, which we can't have if it's a stimulus with an actor pretending to be in pain."

The patients' facial expressions were also analyzed through the Facial Action Coding System (FACS)--a comprehensive, anatomically based system for describing all visually discernible facial movements. The researchers used these FACS values in a formula to provide an objective score of the intensity of the patients' pain facial expressions. This provided a second ground truth for the researchers to use when analyzing the data.

The study participants were asked to gauge the amount of pain they thought the patients in the videos experienced on a scale from zero, labeled as "absolutely no pain," and 100, labeled as "worst pain possible."

In the second experiment, researchers replicated the first portion of this study with 200 participants. This time, after viewing the videos, perceivers were asked to complete the Gender Role Expectation of Pain questionnaire, which measures gender-related stereotypes about pain sensitivity, the endurance of pain, and willingness to report pain.

Perceivers also shared how much medication and psychotherapy they would prescribe to each patient and which of these treatments they believed would be more effective in treating each patient.

The researchers analyzed the results of the participants' responses to the videos compared to the patient's self-reported level of pain and the facial expression intensity data. The ability to analyze observers' perceptions relative to these two ground truth measures of the patients' pain in the videos allowed the researchers to measure bias more accurately, Losin explained. That is because bias could be defined as different ratings for male and female patients despite the same level of responses.

Overall, the study found that female patients were perceived to be in less pain than the male patients who reported, and exhibited, the same intensity of pain. Additional analyses using participants' responses to the questionnaire about gender-related pain stereotypes allowed researchers to conclude that these perceptions were partially explained by these stereotypes.

"If the stereotype is to think women are more expressive than men, perhaps 'overly' expressive, then the tendency will be to discount women's pain behaviors," Losin said. "The flip side of this stereotype is that men are perceived to be stoic, so when a man makes an intense pain facial expression, you think, 'Oh my, he must be dying!' The result of this gender stereotype about pain expression is that each unit of increased pain expression from a man is thought to represent a higher increase in his pain experience than that same increase in pain expression by a woman."

What's more, psychotherapy was chosen as more effective than medication for a higher proportion of female patients compared to male patients.

Additionally, the study concluded that the gender of the perceivers did not influence pain estimation. Both men and women interpreted women's pain to be less intense.

The idea to study disparities in the perception of pain based on a patient's gender was derived from previous research, Losin said, that found women are often prescribed less treatment than men and wait longer to receive that treatment as well.

"There's a pretty wide literature showing demographic differences in pain report, the prevalence of clinical pain conditions, and then also a demographic difference in pain treatments," Losin pointed out. "These differences manifest as disparities because it seems that some people are getting undertreated for their pain based on their demographics."

Moving forward, Losin and her fellow researchers hope this study is a step in identifying and addressing gender disparities in health care. Co-authors of the study included the study's lead author, Lanlan Zhang, Guangzhou Sport University; Yoni K. Ashar, Weill Cornell Medical College; Leonie Koban, Paris Brain Institute; and senior author Tor D. Wager, Dartmouth College.

"I think one critical piece of information that could be conveyed in medical curricula is that people, even those with medical training in other studies, have been found to have consistent demographic biases in how they assess the pain of male and female patients and that these biases impact treatment decisions," Losin remarked. "Critically, our results demonstrate that these gender biases are not necessarily accurate. Women are not necessarily more expressive than men, and thus their pain expression should not be discounted."

INFORMATION:

DETROIT - Researchers at Henry Ford Health System have found that workers in construction and other manufacturing jobs are more susceptible for developing carpal tunnel syndrome than those who work in office jobs.

In a retrospective study published in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, researchers report that manual labor jobs that require lifting, gripping and forceful wrist motion contribute to higher rates of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Injuries related to carpal tunnel have steadily declined from 1.3 million in 2003 to 900,380 in 2018, according to the most recent figures compiled by the U.S. Department ...

Glycine regulates neuronal activity in the brain

Glycine is the smallest amino acid - one of the building blocks of proteins. It acts also as a neurotransmitter in the brain, enabling neurons to communicate with each other and modulating neuronal activity. Many researchers have focused on increasing glycine levels in synapses to find an effective treatment for schizophrenia. This could be done using inhibitors targeting Glycine Transporter 1 (GlyT1), a protein that sits in neuronal cell membranes and is responsible for the uptake of glycine into neurons. However, the development of such drugs has been hampered ...

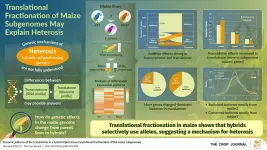

The adage goes, "Two is better than one." Well, that might be true for endeavors involving human heads, but when it comes to ears, hybrid maize tends to have a superior advantage over the parental stocks in most cases. This phenomenon, called hybrid vigor or "heterosis," has been used by agriculturalists across ages to create higher-yielding, more resistant varieties of maize all over the world.

But what are the factors contributing to the increased hybrid vigor of maize? Several different genetic models have been proposed to explain heterosis in varied ...

Pain will lessen over time

Results include longer distance and walking time

8.5 million people in U.S., 250 million worldwide, have PAD

CHICAGO --- No pain means no gain when it comes to reaping exercise benefits for people with peripheral artery disease (PAD), reports a new Northwestern Medicine study.

In people with peripheral artery disease, walking for exercise at an intensity that induces ischemic leg pain (caused by restricted blood flow) improves walking performance -- distance and length of time walking -- the study found. Walking at a slow pace that does not induce ischemic leg symptoms is no more effective than no exercise at all, the study showed.

This randomized trial is the first to show that a home-based walking exercise program ...

Washington, D.C. - April 6, 2021 - A new study has demonstrated that autism spectrum disorder is related to changes in the gut microbiome. The findings are published this week in mSystems, an open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

"Longitudinally, we were able to see that within an individual, changes in the microbiome were associated with changes in behavior," said principal study investigator Catherine Lozupone, PhD, a microbiologist in the Department of Medicine, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado. "If we are going to understand the link between the gut microbiome and autism, we need more collaborative efforts across different regions and ...

Biophysicists from Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet (LMU) in Munich have shown that a phenomenon known as diffusiophoresis, which can lead to a directed particle transport, can occur in biological systems.

In order to perform their biological functions, cells must ensure that their logistical schedules are implemented smoothly, such that the necessary molecular cargoes are delivered to their intended destinations on time. Most of the known transport mechanisms in cells are based on specific interactions between the cargo to be transported and the energy-consuming motor ...

The founding chair of the Biomedical Engineering Department at the University of Houston is reporting a new deep neural network architecture that provides early diagnosis of systemic sclerosis (SSc), a rare autoimmune disease marked by hardened or fibrous skin and internal organs. The proposed network, implemented using a standard laptop computer (2.5 GHz Intel Core i7), can immediately differentiate between images of healthy skin and skin with systemic sclerosis.

"Our preliminary study, intended to show the efficacy of the proposed network architecture, holds promise in the characterization of SSc," reports Metin Akay, John S. Dunn Endowed Chair Professor of biomedical engineering. ...

WASHINGTON--Raindrops on other planets and moons are close to the size of raindrops on Earth despite having different chemical compositions and falling through vastly different atmospheres, a new study finds. The results suggest raindrops falling from clouds are surprisingly similar across a wide range of planetary conditions, which could help scientists better understand the climates and precipitation cycles of other worlds, according to the researchers.

Raindrops on Earth are made of water, but other worlds in our solar system have precipitation made of more unusual stuff. On Venus, ...

As part of an international collaboration, researchers from ELTE Eötvös Loránd University developed a new animal model to study a rare genetic disease that can lead to blindness at the age of 40-50. The new model could open up new perspectives in our understanding of this metabolic disease and will also help to identify new potential drug candidates, according to the recent study published in Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) is a rare genetic disease with symptoms that usually manifest in adolescence or in early adulthood. The symptoms are caused by the appearance of hydroxyapatite crystal deposits in the subcutaneous connective tissue and retina ...

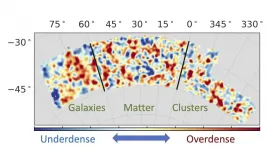

The universe is expanding at an ever-increasing rate, and while no one is sure why, researchers with the Dark Energy Survey (DES) at least had a strategy for figuring it out: They would combine measurements of the distribution of matter, galaxies and galaxy clusters to better understand what's going on.

Reaching that goal turned out to be pretty tricky, but now a team led by researchers at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University and the University of Arizona have come up with a solution. Their analysis, published April 6 in Physical Review ...