(Press-News.org) Ordinary pure water has no distinct taste, but how about heavy water - does it taste sweet, as anecdotal evidence going back to 1930s may have indicated? And if yes - why, when D2O is chemically practically identical to H2O, of which it is a stable naturally-occurring isotope? These questions arose shortly after heavy water was isolated almost 100 years ago, but they had not been satisfactorily answered until now. Now, researchers Pavel Jungwirth and Phil Mason with students Carmelo Tempra and Victor Cruces Chamorro at the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry of the Czech Academy of Sciences (IOCB Prague), together with the group of Masha Niv at the Hebrew University and Maik Behrens at the Technical University of Munich, found answers to these questions using molecular dynamics simulations, cell-based experiments, mouse models, and human subjects. In their research article published in Communications Biology, they show conclusively that, unlike ordinary water, heavy water tastes sweet to humans but not to mice, with this effect being mediated by the human sweet taste receptor.

Heavy water (D2O) differs from normal water (H2O) by an H-D isotopic substitution only, and as such, should not be chemically distinct. Leaving aside a trivial 10% change in density due to the doubled mass of D compared to H, differences in properties of D2O vs H2O, such as pH or melting and boiling points, are indeed very small. These differences are solely due to nuclear quantum effects, namely, changes in zero-point vibrations, which lead to a slightly stronger hydrogen bonding in D2O than in H2O.

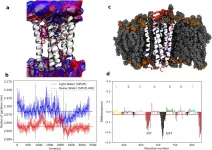

"Despite the fact that the two isotopes are nominally chemically identical, we have shown conclusively that humans can distinguish by taste (which is based on chemical sensing) between H2O and D2O, with the latter having a distinct sweet taste," commented Pavel Jungwirth on the principal result of their study. In their work, the authors complement taste experiments on human subjects with tests on mice and on HEK 293T cells transfected with the human sweet taste receptor TAS1R2/TAS1R3, and with molecular modelling. The results consistently point to the fact that the sweet taste of heavy water is mediated in humans by the TAS1R2/TAS1R3 receptor. Future studies should be able to elucidate the precise sites and mechanisms of action, as well as the reason why D2O activates TAS1R2/TAS1R3 in particular, resulting in a sweet (but not other) taste.

While clearly not a practical sweetener, heavy water provides a glimpse into the wide-open chemical space of sweet molecules. Since heavy water has been used in medical procedures, the finding that it can elicit responses of the sweet taste receptor, which is located not only on the tongue but also in other tissues of the human body, represents an important information for clinicians and their patients. Moreover, due to wide application of D2O in chemical structure determination, chemists will benefit from being aware of the present observations.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that 86 years ago, Science published a short letter by H. C. Urey, Nobelist for the discovery of deuterium (H. C. Urey & G. Failla, Science, 81, 273, 1935. http://doi.org/10.1126/science.81.2098.273-a), stating authoritatively that D2O is undistinguishable from H2O by taste, which had a strong albeit misleading effect on the ongoing discussion about the subject.

"Our study thus resolves an old controversy concerning the sweet taste of heavy water using state-of-the-art experimental and computer modelling approaches, demonstrating that a small nuclear quantum effect can have a pronounced influence on such a basic biological function as taste recognition," concludes Pavel Jungwirth.

INFORMATION:

Original paper: Sweet taste of heavy water. Natalie Ben Abu, Philip E. Mason, Hadar Klein, Nitzan Dubovski, Yaron Ben Shoshan-Galeczki, Einav Malach, Veronika Pražienková, Lenka Maletínská, Carmelo Tempra, Victor Cruces Chamorro, Josef Cvačka, Maik Behrens, Masha Y. Niv and Pavel Jungwirth. Communications Biology 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-01964-y

Professor Pavel Jungwirth, DSc. (born 1966, Prague) is a Czech physical chemist, educator, and popularizer of science. He studied physics in Prague at Charles University, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, where he specialized in chemical physics. He did his PhD work in computational chemistry at the J. Heyrovský Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Czech Academy of Sciences under the guidance of Professor R. Zahradník. He has spent several years abroad as a postdoc and later as a visiting professor, primarily at the University of California, Irvine, the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Currently, Pavel Jungwirth heads a research team at the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry of the Czech Academy of Sciences (https://jungwirth.group.uochb.cz) holding the position of Distinguished Chair. He is also an external member of the Department of Chemical Physics and Optics at the Charles University Faculty of Mathematics and Physics.

Pavel Jungwirth has published more than 300 original papers in international journals, including Science, Nature Chemistry, and PNAS, with over 15,000 citations. He is an executive editor of the Journal of Physical Chemistry, which is published by the American Chemical Society. He is also the president of the Learned Society of the Czech Republic, and has received numerous awards, among them the Spiers Memorial Prize of the British Royal Society of Chemistry, the Jaroslav Heyrovský Honorary Medal for Merit in the Chemical Sciences from the Czech Academy of Sciences, and the Humboldt Research Award. Pavel Jungwirth's popular-science contributions regularly appear on the pages of the weekly Respekt, and he is a frequent Czech Radio and TV guest.

The Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry of the Czech Academy of Sciences / IOCB Prague (https://www.uochb.cz/) is a leading internationally recognized scientific institution whose primary mission is the pursuit of basic research in chemical biology and medicinal chemistry, organic and materials chemistry, chemistry of natural substances, biochemistry and molecular biology, physical chemistry, theoretical chemistry, and analytical chemistry. An integral part of the IOCB Prague's mission is the implementation of the results of basic research in practice. Emphasis on interdisciplinary research gives rise to a wide range of applications in medicine, pharmacy, and other fields.

CLEVELAND--A team of researchers from Case Western Reserve University has discovered a formulation of existing medicines that can significantly reduce the presence of the fungus Candida auris (C. auris) on skin, controlling its spread and potentially keeping it from forming infections that have a high mortality rate.

By using a proprietary formulation of topical medications terbinafine or clotrimazole, researchers prevented the growth and spread of the fungus on the skin of a host; the findings appear in the most recent issue of the journal Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

"It's a very ...

Though the U.S. and South Korea recorded their first official COVID-19 case on the same day, January 20, 2020, there were notable differences in how each country would ultimately address what has become the world's most severe pandemic since 1918.

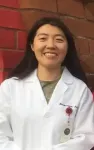

Yoonjung Lee, Pharm.D., Ph.D., a pharmacy preceptor and pharmaceutical sciences researcher at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) Jerry H. Hodge School of Pharmacy, said she was surprised at how South Korea effectively managed the pandemic without the business shutdowns and lockdowns that occurred in China, the U.S. and many European countries.

"I am amazed at how the Korean government had prompt and effective public health interventions to not only address COVID-19, but also to address COVID-19-vulnerable ...

Imagine there are arrows that are lethal when fired on your enemies yet harmless if they fall on your friends. It's easy to see how these would be an amazing advantage in warfare, if they were real. However, something just like these arrows does indeed exist, and they are used in warfare ... just on a different scale.

These weapons are called tailocins, and the reality is almost stranger than fiction.

"Tailocins are extremely strong protein nanomachines made by bacteria," explained Vivek Mutalik, a research scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) who studies tailocins and phages, the bacteria-infecting viruses that tailocins appear to be remnants of. "They ...

AI-powered symptom checkers can potentially reduce the number of people going to in-person clinics during the pandemic, but first, researchers say, people need to know they exist.

COVID symptom checkers are digital self-assessment tools that use AI to help users identify their level of COVID-19 risk and assess whether they need to seek urgent care based on their reported symptoms. These tools also aim to provide reassurance to people who are experiencing symptoms that are not COVID-19 related.

Most platforms, like Babylon and Isabel, are public-facing tools, but the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) has one of the first COVID-19 symptom checkers that is fully integrated with the users' medical ...

Study using electronic health records of 236,379 COVID-19 patients mostly from the USA estimates that one in three COVID-19 survivors (34%) were diagnosed with a neurological or psychiatric condition within six months of infection.

Anxiety (17%) and mood disorders (14%) were the most common. Neurological diagnoses such as stroke and dementia were rarer, but not uncommon in those who had been seriously ill during COVID-19 infection. For example, of those who had been admitted to intensive care, 7% had a stroke and almost 2% were diagnosed with dementia.

These diagnoses were more common in COVID-19 patients than in flu or respiratory tract infection patients ...

Highlight

Most patients with kidney failure who were undergoing hemodialysis developed a positive antibody response after being vaccinated for COVID-19, but their response was lower than that of individuals without kidney disease.

Washington, DC (April 6, 2021) -- In a recent study, most patients with kidney failure who were undergoing hemodialysis developed a substantial antibody response following the vaccination with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine against COVID-19, but it was significantly lower than that of individuals without kidney disease. The findings will appear in an upcoming ...

CHAPEL HILL, NC - A team led by scientists at the UNC School of Medicine identified a molecule called microRNA-29 as a powerful controller of brain maturation in mammals. Deleting microRNA-29 in mice caused problems very similar to those seen in autism, epilepsy, and other neurodevelopmental conditions.

The results, published in Cell Reports, illuminate an important process in the normal maturation of the brain and point to the possibility that disrupting this process could contribute to multiple human brain diseases.

"We think abnormalities in microRNA-29 activity are likely to be a common theme in neurodevelopmental ...

Chestnut Hill, Mass. (4/6/2021) -- Compact logos can encourage favorable brand evaluations by signaling product safety, according to a new study by researchers at Boston College's Carroll School of Management and Indian Institute of Management Udaipur, who reviewed the opinions of 17,000 consumers and conducted additional experiments with a variety of logos.

The findings reveal that typography -- specifically tracking, or the spacing between letters in a word -- can influence consumers' interpretations of brand logos. Further, the interpretation is influenced by cultural factors, the researchers reported ...

Fossil discoveries often help answer long-standing questions about how our modern world came to be. However, sometimes they only deepen the mystery--as a recent discovery of four new species of ancient insects in British Columbia and Washington state is proving.

The fossil species, recently discovered by paleontologists Bruce Archibald of Simon Fraser University and Vladimir Makarkin of the Russian Academy of Sciences, are from a group of insects known as snakeflies, now shown to have lived in the region some 50 million years ago. The findings, published in Zootaxa, raise more questions about the evolutionary history of the distinctly elongated insects and why they live where they do today.

Snakeflies are slender, predatory insects that are native to the Northern Hemisphere ...

Starting your day by thinking about what kind of leader you want to be can make you more effective at work, a new study finds.

"It's as simple as taking a few moments in the morning while you're drinking your coffee to reflect on who you want to be as a leader," said Remy Jennings, a doctoral student in the University of Florida's Warrington College of Business, who authored the study in the journal Personnel Psychology with UF management professor Klodiana Lanaj.

When study participants took that step, they were more likely to report helping co-workers and providing ...