(Press-News.org) Analysis by international team including University of Warwick of the first transiting exoplanet that was discovered has revealed six different chemicals in its atmosphere.

It is the first time that so many molecules have been measured, and points to an atmosphere with more carbon present than oxygen

This chemical fingerprint is typical of a planet that formed much further away from its sun than the current location, a mere 7 million km from the star

Study tests techniques that will be useful for detecting signs of potentially habitable planets when more powerful telescopes come online

Artist's impression available - see Notes to Editors

Astronomers have found evidence that the first exoplanet that was identified transiting its star could have migrated to a close orbit with its star from its original birthplace further away.

Analysis of the planet's atmosphere by a team including University of Warwick scientists has identified the chemical fingerprint of a planet that formed much further away from its sun than it currently resides. It confirms previous thinking that the planet has moved to its current position after forming, a mere 7 million km from its sun or the equivalent of 1/20th the distance from the Earth to our Sun.

The conclusions are published today (7 April) in the journal Nature by an international team of astronomers. The University of Warwick led the modelling and interpretation of the results which mark the first time that as many as six molecules in the atmosphere of an exoplanet have been measured to determine its composition.

It is also the first time that astronomers have used these six molecules to definitively pinpoint the location at which these hot, giant planets form thanks to the composition of their atmospheres.

With new, more powerful telescopes coming online soon, their technique could also be used to study the chemistry of exoplanets that could potentially host life.

This latest research used the Telescopio Nazionale Galileo in La Palma, Spain, to acquire high-resolution spectra of the atmosphere of the exoplanet HD 209458b as it passed in front of its host star on four separate occasions. The light from the star is altered as it passes through the planet's atmosphere and by analysing the differences in the resulting spectrum astronomers can determine what chemicals are present and their abundances.

For the first time, astronomers were able to detect hydrogen cyanide, methane, ammonia, acetylene, carbon monoxide and low amounts of water vapour in the atmosphere of HD 209458b. The unexpected abundance of carbon-based molecules (hydrogen cyanide, methane, acetylene and carbon monoxide) suggests that there are approximately as many carbon atoms as oxygen atoms in the atmosphere, double the carbon expected. This suggests that the planet has preferentially accreted gas rich in carbon during formation, which is only possible if it orbited much further out from its star when it originally formed, most likely at a similar distance to Jupiter or Saturn in our own solar system.

Dr Siddharth Gandhi of the University of Warwick Department of Physics said: "The key chemicals are carbon-bearing and nitrogen-bearing species. If these species are at the level we've detected them, this is indicative of an atmosphere that is enriched in carbon compared to oxygen. We've used these six chemical species for the first time to narrow down where in its protoplanetary disc it would have originally formed.

"There is no way that a planet would form with an atmosphere so rich in carbon if it is within the condensation line of water vapour. At the very hot temperature of this planet (1,500K), if the atmosphere contains all the elements in the same proportion as in the parent star, oxygen should be twice more abundant than carbon and mostly bonded with hydrogen to form water or to carbon to form carbon monoxide. Our very different finding agrees with the current understanding that hot Jupiters like HD 209458b formed far away from their current location."

Using models of planetary formation, the astronomers compared HD 209458b's chemical fingerprint with what they would expect to see for a planet of that type.

A solar system begins life as a disc of material surrounding the star which gathers together to form the solid cores of planets, which then accrete gaseous material to form an atmosphere. Close to the star where it is hotter, a large proportion of oxygen remains in the atmosphere in water vapour. Further out, as it gets cooler, that water condenses to become ice and is locked into a planet's core, leaving an atmosphere more heavily comprised of carbon- and nitrogen-based molecules. Therefore, planets orbiting close to the sun are expected to have atmospheres rich in oxygen, rather than carbon.

HD 209458b was the first exoplanet to be identified using the transit method, by observing it as it passed in front of its star. It has been the subject of many studies, but this is the first time that six individual molecules have been measured in its atmosphere to create a detailed 'chemical fingerprint'.

Dr Matteo Brogi from the University of Warwick team adds: "By scaling up these observations, we'll be able to tell what classes of planet we have out there in terms of their formation location and early evolution. It's really important that we don't work under the assumptions that there is only a couple of molecular species that are important to determine the spectra of these planets, as has frequently been done before. Detecting as many molecules as possible is useful when we move on to testing this technique on planets with conditions that are amenable for hosting life, because we will need to have a full portfolio of chemical species we can detect."

Paolo Giacobbe, researcher at the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) and lead author of the paper, said: "If this discovery were a novel it would begin with 'In the beginning there was only water...' because the vast majority of the inference on exoplanet atmospheres from near-infrared observations was based on the presence (or absence) of water vapour, which dominates this region of the spectrum. We asked ourselves: is it really possible that all the other species expected from theory do not leave any measurable trace? Discovering that it is possible to detect them, thanks to our efforts in improving analysis techniques, opens new horizons to be explored."

INFORMATION:

* 'Five carbon- and nitrogen-bearing species in a hot giant planet atmosphere' will be published in Nature, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03381-x Link: https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03381-x (to go live when embargo lifts)

This study received funding from the Science and Technology Facilities Council, part of UK Research and Innovation, and the Italian Space Agency.

Notes to editors:

Artist's impressions of HD 209458b available to download at the link below. Images are free for use if used in direct connection with this story but image copyright and credit must be University of Warwick/Mark Garlick:

https://warwick.ac.uk/services/communications/medialibrary/images/march_2021/exoplanet_3.jpg

https://warwick.ac.uk/services/communications/medialibrary/images/march_2021/exoplanet_portrait.jpg

Caption: Exoplanet HD 209458b transits its star. The illuminated crescent and its colours have been exaggerated to illustrate the light spectra that the astronomers used to identify the six molecules in its atmosphere. Credit: University of Warwick/Mark Garlick

A new clinical trial from King's College London's Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, & Neuroscience, in collaboration with Oxford University, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Sussex University, and Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust has established an innovative therapy as an effective means of treating paranoid thoughts in people experiencing psychosis.

In research published in JAMA Psychiatry today, participants of the SlowMo therapy trial had eight face-to-face therapy sessions with support from an interactive web platform and app. The app, designed in collaboration with people experiencing psychosis and the Royal College of Art, is used outside the clinic to help individuals feel safer in daily life.

Paranoia is fuelled ...

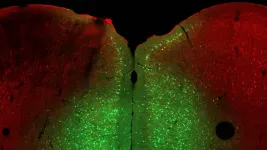

Everyone faces stress occasionally, whether in school, at work, or during a global pandemic. However, some cannot cope as well as others. In a few cases, the cause is genetic. In humans, mutations in the OPHN1 gene cause a rare X-linked disease that includes poor stress tolerance. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor Linda Van Aelst seeks to understand factors that cause specific individuals to respond poorly to stress. She and her lab studied the mouse gene Ophn1, an analog of the human gene, which plays a critical role in developing brain cell connections, memories, and stress tolerance. When Ophn1 was removed in a specific part of the ...

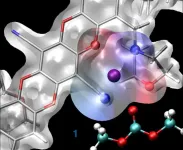

Membranes that allow certain molecules to quickly pass through while blocking others are key enablers for energy technologies from batteries and fuel cells to resource refinement and water purification. For example, membranes in a battery separating the two terminals help to prevent short circuits, while also allowing the transport of charged particles, or ions, needed to maintain the flow of electricity.

The most selective membranes - those with very specific criteria for what may pass through - suffer from low permeability for the working ion in the battery, which limits the battery's power and energy efficiency. ...

The landscape of sloping vineyards on the banks of the River Mosel in Germany is a characteristic symbol of a region, which cannot be understood without its wine: the Mosel wine region. Tourists from all over the world, especially from the neighbouring countries of Belgium, Luxembourg, and The Netherlands visit the area in search of mountains and wine. However, the lack of new generations and the increase in temperatures and short heavy summer rainfall events caused by climate change endanger the production of wine.

In this sense, the European H2020 ...

It was found that event horses that wear thin or thick bits in events had a greater risk of moderate or severe oral lesions compared to horses wearing medium-sized bits, while straight bits were associated with lesions in the bars of the horse's mouth.

"Our recommendation is to use a jointed bit of moderate thickness, that is 14 to 17 millimetres, if the size of the mouth is not known, paying particular attention to the handling of mares and both warmblood and coldblood event horses. They were seen to have a greater risk of mouth lesions compared to geldings and ponies," says doctoral student and veterinarian ...

The global production of sheep's milk is one the rise, in the vast majority of cases used to produce cheese. However, a relatively large amount of milk is needed to produce it, so science is looking for ways to increase its yield; that is, to obtain more cheese using less milk.

Immersed in this task, a team from the Department of Animal Production at the University of Cordoba, led by Professor Ana Garzón, has collaborated with the University of Leon in the search for genetic parameters affecting the cheese production of milk from Churra sheep, one of the oldest and most rustic breeds on the Iberian Peninsula.

After analysing traits related to rennet and milk properties (pH, ...

The way we move says a lot about the state of our brain. While normal motor behaviour points to a healthy brain function, deviations can indicate impairments owing to neurological diseases. The observation and evaluation of movement patterns is therefore part of basic research, and is likewise one of the most important instruments for non-invasive diagnostics in clinical applications. Under the leadership of computer scientist Prof. Dr Björn Ommer and in collaboration with researchers from Switzerland, a new computer-based approach in this context has been developed at Heidelberg University. As studies inter alia with human test persons have shown, this approach enables the fully automatic ...

It is more complicated than copy and paste, but digital twins could be way of future manufacturing according to researchers from the University of Kentucky. They developed a virtual environment based on human-robot interactions that can mirror the physical set up of a welder and their project. Called a digital twin, the prototype has implications for evolving manufacturing systems and training novice welders. They published their work in the IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica (Volume 8, Issue 2, February 2021).

"This human-robot interaction working style helps to enhance the human users' operational productivity and ...

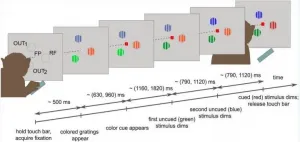

To effectively perform any daily task, the human brain needs to process information from the outside world using various cognitive functions. This cognitive processing passes through a dense interconnected network of cells whose physiology is specialized. The interconnected cell network needs to perform this processing of information efficiently and interact cooperatively to provide us, in real time, with useful instructions for living.

Research published on 23 March in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America challenges recent scientific advances seeking to find out how cognitive control and sensory information relate to the cortical machinery ...

New research has for the first time compared images of the protein spikes that develop on the surface of cells exposed to the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine to the protein spike of the SARS-CoV-19 coronavirus. The images show that the spikes are highly similar to those of the virus and support the modified adenovirus used in the vaccine as a leading platform to combat COVID-19.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19, has a large number of spikes sticking out of its surface that it uses to attach to, and enter, cells in the human body. These spikes are coated in sugars, known as ...