The muon's magnetic moment fits just fine

A new estimate of the strength of the sub-atomic particle's magnetic field aligns with the standard model of particle physics

2021-04-07

(Press-News.org) A new estimation of the strength of the magnetic field around the muon--a sub-atomic particle similar to, but heavier than, an electron--closes the gap between theory and experimental measurements, bringing it in line with the standard model that has guided particle physics for decades.

A paper describing the research by an international team of scientists appears April 8, 2021 in the journal Nature.

Twenty years ago, in an experiment at Brookhaven National Laboratory, physicists detected what seemed to be a discrepancy between measurements of the muon's "magnetic moment"--the strength of its magnetic field--and theoretical calculations of what that measurement should be, raising the tantalizing possibility of physical particles or forces as yet undiscovered. The new finding shrinks this discrepancy, suggesting that the muon's magnetism is likely not mysterious at all. To achieve this result, instead of relying on experimental data, researchers simulated every aspect of their calculations from the ground up--a task requiring massive supercomputing power.

"Most of the phenomena in nature can be explained by what we call the 'standard model' of particle physics," said Zoltan Fodor, professor of physics at Penn State and a leader of the research team. "We can predict the properties of particles extremely precisely based on this theory alone, so when theory and experiment don't match up, we can get excited that we might have found something new, something beyond the standard model."

For a discovery of new physics beyond the standard model, there is consensus among physicists that the disagreement between theory and measurement must reach five sigma--a statistical measure that equates to a probability of about 1 in 3.5 million.

In the case of the muon, measurements of its magnetic field deviated from the existing theoretical predictions by about 3.7 sigma. Intriguing, but not enough to declare a discovery of a new break in the rules of physics. So, researchers set out to improve both the measurements and the theory in the hopes of either reconciling theory and measurement or increasing the sigma to a level that would allow the declaration of a discovery of new physics.

"The existing theory for estimating the strength of the muon's magnetic field relied on experimental electron-positron annihilation measurements," said Fodor. "In order to have another approach, we used a fully verified theory that was completely independent of reliance on experimental measurements. We started with rather basic equations and built the entire estimation from the ground up."

The new calculations required hundreds of millions of CPU hours at multiple supercomputer centers in Europe and bring theory back in line with measurement. However, the story is not over yet. New, more precise experimental measurements of the muon's magnetic moment are expected soon.

"If our calculations are correct and the new measurements do not change the story, it appears that we don't need any new physics to explain the muon's magnetic moment--it follows the rules of the standard model," said Fodor. "Although, the prospect of new physics is always enticing, it's also exciting to see theory and experiment align. It demonstrates the depth of our understanding and opens up new opportunities for exploration."

The excitement is far from over.

"Our result should be cross-checked by other groups and we anticipate them," said Fodor. "Furthermore, our finding means that there is a tension between the previous theoretical results and our new ones. This discrepancy should be understood. In addition, the new experimental results might be close to old ones or closer to the previous theoretical calculations. We have many years of excitement ahead of us."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Fodor, the research team includes Szabolcs Borsanyi, Jana N. Guenther, Christian Hoelbling, Sandor D. Katz, Laurent Lellouch, Thomas Lippert, Laurent Lellouch, Kohtaroh Miura, Letizia Parato, Kalman K. Szabo, Finn Stokes, Balint C. Toth, Csaba Torok, Lukas Varnhorst.

Participating institutions include Penn State, the University of Wuppertal in Germany; the Jülich Supercomputing Centre in Germany; Eötvös University in Budapest, Hungary; the University of California, San Diego; the University of Regensburg in Germany; Aix Marseille Univ, Université de Toulon in Marseille, France; Helmholtz Institute Mainz in Germany; the Kobayashi-Maskawa Institute for the Origin of Particles and the Universe, Nagoya University in Japan.

The research was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG); the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF); the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office; and the Excellence Initiative of Aix-Marseille, a French Investissements d'Avenirf program, through the Chaire d'Excellence initiative and the Laboratoire d'Excellence.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-07

What The Study Did: Researchers report on the observation of a newly associated mucocutaneous eruption in a pediatric patient with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection

Authors: Zachary E. Holcomb, M.D., of Boston Children's Hospital, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0385)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study is linked to this news release.

Embed this link to provide your readers ...

2021-04-07

What The Study Did: In this observational study of 3.4 million live births in 2018, criminalizing immigrant policies were associated with higher rates of preterm birth for Black women born outside the U.S., while inclusive immigrant policies were associated with lower preterm birth for all women born outside the U.S.,particularly White women born outside the U.S.

Authors: May Sudhinaraset, Ph.D., of the Jonathan and Karin Fielding School of Public Health at the University of California, Los Angeles, is the corresponding author.

To access the ...

2021-04-07

What The Study Did: Researchers projected to the year 2040 what will become the most common and deadly cancers in the United States.

Authors: Lola Rahib, Ph.D., of Cancer Commons in Mountain View, California, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4708)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and ...

2021-04-07

What The Study Did: Questionnaire responses were compared to examine whether transgender children and teens experience significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression than their cisgender peers.

Authors: Dominic J. Gibson, Ph.D., of the University of Washington in Seattle, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4739)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, ...

2021-04-07

Ancient DNA from Neandertals and early modern humans has recently shown that the groups likely interbred somewhere in the Near East after modern humans left Africa some 50,000 years ago. As a result, all people outside Africa carry around 2% to 3% Neandertal DNA. In modern human genomes, those Neandertal DNA segments became increasingly shorter over time and their length can be used to estimate when an individual lived. Archaeological data published last year furthermore suggests that modern humans were already present in southeastern Europe 47-43,000 years ago, but due to a scarcity of fairly complete human fossils and the lack of genomic DNA, there is little understanding of who these early human colonists were - or of their relationships to ancient and present-day ...

2021-04-07

Analysis by international team including University of Warwick of the first transiting exoplanet that was discovered has revealed six different chemicals in its atmosphere.

It is the first time that so many molecules have been measured, and points to an atmosphere with more carbon present than oxygen

This chemical fingerprint is typical of a planet that formed much further away from its sun than the current location, a mere 7 million km from the star

Study tests techniques that will be useful for detecting signs of potentially habitable planets when more powerful telescopes come online

Artist's impression available - see Notes to Editors

Astronomers have found ...

2021-04-07

A new clinical trial from King's College London's Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, & Neuroscience, in collaboration with Oxford University, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Sussex University, and Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust has established an innovative therapy as an effective means of treating paranoid thoughts in people experiencing psychosis.

In research published in JAMA Psychiatry today, participants of the SlowMo therapy trial had eight face-to-face therapy sessions with support from an interactive web platform and app. The app, designed in collaboration with people experiencing psychosis and the Royal College of Art, is used outside the clinic to help individuals feel safer in daily life.

Paranoia is fuelled ...

2021-04-07

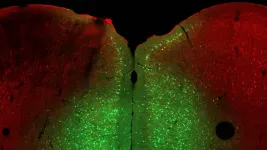

Everyone faces stress occasionally, whether in school, at work, or during a global pandemic. However, some cannot cope as well as others. In a few cases, the cause is genetic. In humans, mutations in the OPHN1 gene cause a rare X-linked disease that includes poor stress tolerance. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor Linda Van Aelst seeks to understand factors that cause specific individuals to respond poorly to stress. She and her lab studied the mouse gene Ophn1, an analog of the human gene, which plays a critical role in developing brain cell connections, memories, and stress tolerance. When Ophn1 was removed in a specific part of the ...

2021-04-07

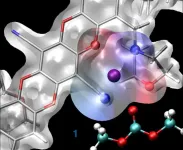

Membranes that allow certain molecules to quickly pass through while blocking others are key enablers for energy technologies from batteries and fuel cells to resource refinement and water purification. For example, membranes in a battery separating the two terminals help to prevent short circuits, while also allowing the transport of charged particles, or ions, needed to maintain the flow of electricity.

The most selective membranes - those with very specific criteria for what may pass through - suffer from low permeability for the working ion in the battery, which limits the battery's power and energy efficiency. ...

2021-04-07

The landscape of sloping vineyards on the banks of the River Mosel in Germany is a characteristic symbol of a region, which cannot be understood without its wine: the Mosel wine region. Tourists from all over the world, especially from the neighbouring countries of Belgium, Luxembourg, and The Netherlands visit the area in search of mountains and wine. However, the lack of new generations and the increase in temperatures and short heavy summer rainfall events caused by climate change endanger the production of wine.

In this sense, the European H2020 ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] The muon's magnetic moment fits just fine

A new estimate of the strength of the sub-atomic particle's magnetic field aligns with the standard model of particle physics