(Press-News.org) BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Race associates with the risk of death from end-stage heart failure. So, identifying the molecular determinants of that risk may help the pursuit of the novel diagnosis and prognosis of heart failure, and its therapy.

A University of Alabama at Birmingham study of end-stage heart-failure patients has found that cytosine-p-guanine, or CpG, methylation of the DNA in the heart has a bimodal distribution among the patients, and that race -- African American versus Caucasian -- was the sole variable in patient records that explained the difference. A subsequent look at the census tracts where the patients lived showed that the African American subjects lived in neighborhoods with more racial diversity and poverty, suggesting that the underlying variable may be a socioeconomic difference.

Methylation of DNA is a form of epigenetics, an indirect method of gene regulation that can change with gene-environment interaction. Previously the Wende laboratory has shown that these DNA modifications differentiate ischemic and non-ischemic heart failure.

The current UAB study included a pilot cohort of 11 heart-failure patients, followed by a testing cohort of 31 heart-failure patients, all of them male. The heart muscle tissue for the study was obtained when patients underwent surgery to install a left ventricular assist device, or LVAD -- a small mechanical pump carried outside the body that helps a weakened heart pump blood. During the surgery, a piece of the left ventricle is excised; it is otherwise discarded but could be used for this study.

Heretofore, epigenetics has been an underexplored source of heterogeneity among patients with end-stage heart failure. The UAB researchers found differential promoter hyper-methylation of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism among African American heart muscle samples, relative to Caucasian samples, and also higher expression of lipogenesis genes. Such metabolic perturbations are a pathological hallmark of end-stage heart failure, as the heart gets more of its energy from glycolysis -- that is from glucose sugar -- as it fails.

This finding generated two hypotheses, says Adam R. Wende, Ph.D., the associate professor in the UAB Department of Pathology who led the study: 1) that the epigenetic remodeling of cardiac gene regulation determines the therapeutic potential of LVADs, and 2) that epigenetic reprogramming of cardiac gene regulation constitutes a mechanism that may influence responsiveness to LVAD-induced cardiac unloading, meaning possible improvement of the heart as the pump takes over part of the work.

In contrast to the hyper-methylated promoters, the genes that had differentially hypo-methylated promoters, or lower levels of methylation, in African American hearts disproportionately represented inflammatory signaling cascades.

Additionally, the UAB researchers did a retrospective analysis of deaths from any cause in the 31 testing cohort patients two years after heart pump implantation. African Americans had a significantly higher rate of death, eight of 15 patients, versus Caucasians, two of 14.

The need for better treatment of heart failure is great. Only half of heart-failure patients respond to medical management, and African Americans experience worse clinical outcomes than any United States race or ethnicity.

"African Americans with heart failure are hospitalized at a rate 2.5-times higher than other races or ethnicities," Wende said. "Furthermore, despite a threefold higher mortality from heart-failure complications, the prevalence of heart failure among African Americans continues to increase."

"It is estimated that 3.6 percent of this community will live with heart failure by 2030, exceeding the predicted prevalence of any other race or ethnicity in America," Wende said. "Therefore, it is paramount to identify and address the issues that underly these disturbing racial differences in heart-failure morbidity and mortality."

The UAB researchers noted the limitation that this was a single-center study; but Wende said, "Nevertheless, we provide preliminary evidence that socioeconomic factors are likely associated with racial differences in cardiac DNA methylation among men with end-stage heart failure."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors with Wende and first author Mark Pepin, M.D., Ph.D., in the study, "Racial and socioeconomic disparity associates with differences in cardiac DNA methylation among men with end-stage heart failure," published in the American Journal of Physiology: Heart and Circulatory Physiology, are Chae-Myeong Ha, Luke A. Potter and Sayan Bakshi, Division of Molecular and Cellular Pathology, UAB Department of Pathology; Joseph P. Barchue, Ayman Haj Asaad, Steven M. Pogwizd and Salpy V. Pamboukian, Division of Cardiovascular Disease, UAB Department of Medicine; Bertha A. Hidalgo, Department of Epidemiology, UAB School of Public Health; and Selwyn M. Vickers, Office of the Dean and Senior Vice President for Medicine, UAB School of Medicine.

Support came from National Institutes of Health grants MD008620 Center for Healthy African American Men through Partnerships, or CHAAMPS, TR001417, HL133011, HL137240 and HL154571.

Pepin, now at the Institute for Experimental Cardiology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Germany, did his research as a graduate student in UAB's Medical Scientist Training Program, an integrated M.D.-Ph.D. program.

More than 20 years after the discovery of the parkin gene linked to young-onset Parkinson's disease, researchers at The Ottawa Hospital and the University of Ottawa may have finally figured out how this mysterious gene protects the brain.

Using human and mouse brain samples and engineered cells, they found that the parkin protein works in two ways. First, it acts like a powerful antioxidant that disarms potentially harmful oxidants in the brain, including dopamine radicals. Second, as the brain ages and dopamine radicals continue to build up, parkin sequesters these harmful molecules in a special storage site within vulnerable nerve cells, so they can continue to ...

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va. -- If, as the saying goes, less is more, why do we humans overdo so much?

In a new paper featured on the cover of Nature, University of Virginia researchers explain why people rarely look at a situation, object or idea that needs improving -- in all kinds of contexts -- and think to remove something as a solution. Instead, we almost always add some element, whether it helps or not.

The team's findings suggest a fundamental reason that people struggle with overwhelming schedules, that institutions bog down in proliferating red tape, and, of particular ...

Mobility tracking using cell phone data showing greater movement of people is a strong predictor of increased rates of COVID-19, according to new data in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

"This study shows that mobility strongly predicts [severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2] SARS-CoV-2 growth rate up to 3 weeks in the future, and that stringent measures will continue to be necessary through spring 2021 in Canada," writes Dr. Kevin Brown, Public Health Ontario, with coauthors.

Until Canadians are widely vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, nonpharmaceutical public health interventions such as physical distancing and limiting social contact will be the main population-based means of controlling the spread of the virus.

"Mobility ...

While studying genetic diversity in bumblebees in the Rocky Mountains, USA, researchers from Uppsala University discovered a new species. They named it Bombus incognitus and present their findings in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Bumblebees are vital for agriculture and the natural world due to their role in plant pollination. There are more than 250 species of bumblebee, and they are found mainly in northern temperate regions of the planet. Alarmingly, many species are declining due to the effects of climate change, and those with alpine and arctic habitats are particularly threatened. However, the full diversity of bumblebee ...

The hormone auxin is of central importance for the development of plants. Scientists at the University of Bayreuth and the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen have now developed a novel sensor that makes the spatial distribution of auxin in the cells of living plants visible in real time. The sensor opens up completely new insights into the inner workings of plants for researchers. Moreover, the influences of changing environmental conditions on growth can now also be quickly detected. The team presents its research results in the journal Nature.

The effects of the plant hormone auxin were first described ...

Ants react to social isolation in a similar way as do humans and other social mammals. A study by an Israeli-German research team has revealed alterations to the social and hygienic behavior of ants that had been isolated from their group. The research team was particularly surprised by the fact that immune and stress genes were downregulated in the brains of the isolated ants. "This makes the immune system less efficient, a phenomenon that is also apparent in socially isolating humans - notably at present during the COVID-19 crisis," said Professor Susanne Foitzik, who headed up the study at Johannes ...

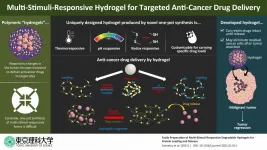

Cancer therapy in recent times relies on the use of several drugs derived from biological sources including different bacteria and viruses, among others. However, these bio-based drugs get easily degraded and therefore inactivated on administration into the body. Thus, effective delivery to and release of these drugs at target tumor sites are of paramount importance from the perspective of cancer therapy.

Recently, scientists have discovered unique three-dimensional, water-containing polymers, called hydrogels, as effective drug delivery systems (DDSs). Drugs loaded into these hydrogels remain relatively stable owing to the network-like structure and organic tissue-like consistency of these DDSs. Besides, drug release from hydrogels can ...

By Karina Ninni | Agência FAPESP – A multidisciplinary research group affiliated with the Department of Physical Education’s Human Movement Laboratory (Movi-Lab) at São Paulo State University (UNESP) in Bauru, Brazil, measured step length synergy while crossing obstacles in patients with Parkinson’s disease and concluded that it was 53% lower than in healthy subjects of the same age and weight. Step length is one of the main variables affected by the disease.

Synergy, defined as combined operation, refers in this case to the capacity of the locomotor (or musculoskeletal) system to adapt movement while crossing an obstacle, combining factors such as speed and foot position, for example. Improving synergy in Parkinson’s patients while they ...

You might not think an animal made out of stone would have much to worry about in the way of predators, and that's largely what scientists had thought about coral. Although corallivores like parrotfish and pufferfish are well known to biologists, their impact on coral growth and survival was believed to be small compared to factors like heatwaves, ocean acidification and competition from algae.

But researchers at UC Santa Barbara have found that young corals are quite vulnerable to these predators, regardless of whether a colony finds itself alone on the reef or surrounded by others of its kind. The research, led by doctoral student Kai Kopecky, appears in the journal Coral Reefs.

Kopecky and his co-authors ...

Unusual diseases are medical mysteries that fascinate us, and one such disease is multiple system atrophy, or MSA. This rare neurological disorder causes failures in the proper functioning of the body's autonomic system (processes that are not under our conscious control, such as blood pressure, breathing, and involuntary movement). The resulting symptoms can look like two other types of neurodegenerative disease: Parkinson's disease and cerebellar ataxia. In fact, MSA can be separated into a parkinsonism subtype or a cerebellar subtype based on whether the resultant movement-related ...