INFORMATION:

Crohn's disease may be caused by immune signaling failure

Study reveals how T cells in the small intestine respond to bile acids, offering localized treatment direction for a cause of chronic illness

2021-04-07

(Press-News.org) JUPITER, FL - People with Crohn's disease are typically treated with powerful anti-inflammatory medications that act throughout their body, not just in their digestive tract, creating the potential for unintended, and often serious, side effects. New research from the lab of Mark Sundrud, PhD, at Scripps Research, Florida suggests a more targeted treatment approach is possible.

Crohn's disease develops from chronic inflammation in the digestive tract, often the small intestine. More than half a million people in the United States live with the disease, which can be debilitating and require repetitive surgeries to remove irreversibly damaged intestinal tissue.

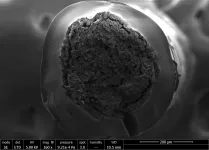

Writing in the journal Nature on April 7, Sundrud's team finds that certain immune cells in the small intestine have evolved a molecular sensing mechanism to protect themselves from the toxic effects of high bile acid concentrations there. This sensory mechanism can be manipulated with small drug-like molecules, they find, and the treatment reduced small bowel inflammation in mice.

"It seems that these immune cells, called T effector cells, have learned how to protect themselves from bile acids," Sundrud says. "These T cells utilize an entire network of genes to interact safely with bile acids in the small intestine. This pathway may malfunction in at least some individuals with Crohn's disease."

Bile acids are made in the liver and released during a meal to help with digestion and absorption of fats and fat-soluble vitamins. They are actively recaptured at the end of the small intestine, in an area called the ileum, where they pass through layers of tissue that contain the body's dense network of intestinal immune cells, and ultimately re-enter the blood stream for return to the liver.

Because they are detergents, bile acids can cause toxicity and inflammation if the system becomes unbalanced. The whole process is kept humming along thanks to an intricate signaling system. Receptors in the nucleus of both liver cells and intestinal barrier cells sense the presence of bile acid and tell the liver to back off on bile acid production if there's too much, or to produce more if there aren't enough to digest a big steak dinner, for example.

Given how damaging bile acids can potentially be to cells, scientists have wondered how immune cells that live in or visit the small intestine tolerate their presence at all. Sundrud's team previously reported that a gene called MDR1, also known as ABCB1, becomes activated when an important subset of immune cells that circulate in blood, called CD4+ T cells, make their way into the small intestine. There, MDR1 acts in transitory T cells to suppress bile acid toxicity and small bowel inflammation.

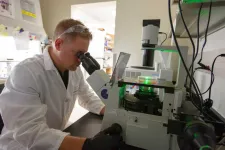

In the new study, Sundrud's team uses an advanced genetic screening approach to uncover how T cells sense and respond to bile acids in the small intestine to increase MDR1 activity.

"The basic discovery that T cells dedicate so much of their time and energy to preventing bile acid-driven stress and inflammation highlights completely new concepts in how we think about and treat Crohn's disease," Sundrud says. "It's like we've been digging in the wrong spot for treasure, and this work gives us a new map showing where X marks the spot."

The T cells contain a receptor molecule in their nucleus known as CAR, short for constitutive androstane receptor. Acting in the small intestine, CAR promotes expression of MDR1, and also plays a role in activating an essential anti-inflammatory gene, IL-10, the team found.

"When we treated mice with drug-like small molecules that activate CAR, the result was localized detoxification of bile acids and reduction of inflammation," Sundrud says.

Sundrud says exploring the therapeutic potential of CAR activation will require caution and creativity, because CAR is also critical for breaking down and eliminating other substances in the liver, including many medicines.

"Ultimately, the Crohn's disease therapy that emerges from this work could be something that activates CAR locally in small intestinal T cells, or something that targets another gene that is similarly responsible for promoting the safe communication between small intestinal T cells and bile acids," Sundrud says.

Also interesting, the team found that the bile acid-inflammation feedback system worked somewhat differently in the colon in concert with gut microbiome factors. While gut flora had more influence on T cell development and function in the colon, it was the nuclear receptor CAR that had more influence on inflammation in the small intestine.

Inflammation plays both positive and negative roles in the body. It can damage tissue, but it also suppresses cancer growth and fights infections. The current anti-inflammatory treatments shut it down systemically, throughout the entire body. That can have potentially serious consequences, such as lowering resistance to infections or easing off the brake on cancer. Directing treatment for inflammatory diseases only to the affected tissue would be preferable whenever feasible, he says.

"The roughly 50 million people living in the US with some sort of autoimmune or chronic inflammatory disease are all treated the same, medically," Sundrud says. "The holy grail would be to come up with druggable approaches to treat inflammation in only specific tissues and leave the rest of the immune cells in your body untouched, and able to fend of cancer and microbial infections."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Carbon dioxide levels reflect COVID-19 risk

2021-04-07

Tracking carbon dioxide levels indoors is an inexpensive and powerful way to monitor the risk of people getting COVID-19, according to new research from the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) and the University of Colorado Boulder. In any given indoor environment, when excess CO2 levels double, the risk of transmission also roughly doubles, two scientists reported this week in Environmental Science & Technology Letters.

The chemists relied on a simple fact already put to use by other researchers more than a decade ago: Infectious people exhale ...

WHOI and NOAA release report on U.S. socio-economic effects of harmful algal blooms

2021-04-07

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) occur in all 50 U.S. states and many produce toxins that cause illness or death in humans and commercially important species. However, attempts to place a more exact dollar value on the full range of these impacts often vary widely in their methods and level of detail, which hinders understanding of the scale of their socio-economic effects.

In order to improve and harmonize estimates of HABs impacts nationwide, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Center for Coastal Ocean Science (NCCOS) and the U.S. National Office for Harmful Algal Blooms at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) convened a workshop led by WHOI Oceanographer ...

Field guides: Argonne scientists bolster evidence of new physics in Muon g-2 experiment

2021-04-07

Scientists are testing our fundamental understanding of the universe, and there's much more to discover.

What do touch screens, radiation therapy and shrink wrap have in common? They were all made possible by particle physics research. Discoveries of how the universe works at the smallest scale often lead to huge advances in technology we use every day.

Scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, along with collaborators from 46 other institutions and seven countries, are conducting an experiment to put our current understanding of the universe to the test. The first result points to the existence of undiscovered particles or forces. This new physics could help explain long-standing ...

First results from Fermilab's Muon g-2 experiment strengthen evidence of new physics

2021-04-07

AMHERST Mass. - The long-awaited first results from the Muon g-2 experiment at the U.S. Department of Energy's Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory show fundamental particles called muons behaving in a way that is not predicted by scientists' best theory, the Standard Model of particle physics. This landmark result, made with unprecedented precision and to which UMass Amherst's David Kawall's research group made key contributions, confirms a discrepancy that has been gnawing at researchers for decades.

"Today is an extraordinary day, long awaited ...

Surgical sutures inspired by human tendons

2021-04-07

Sutures are used to close wounds and speed up the natural healing process, but they can also complicate matters by causing damage to soft tissues with their stiff fibers. To remedy the problem, researchers from Montreal have developed innovative tough gel sheathed (TGS) sutures inspired by the human tendon.

These next-generation sutures contain a slippery, yet tough gel envelop, imitating the structure of soft connective tissues. In putting the TGS sutures to the test, the researchers found that the nearly frictionless gel surface mitigated the damage typically ...

Research brief: Reflecting sunlight could cool the Earth's ecosystem

2021-04-07

Published in the Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences, researchers in the Climate Intervention Biology Working Group -- including Jessica Hellmann from the University of Minnesota Institute on the Environment -- explored the effect of solar climate interventions on ecology.

Composed of climate scientists and ecologists from leading research universities internationally, the team found that more research is needed to understand the ecological impacts of solar radiation modification (SRM) technologies that reflect small amounts of sunlight back into space. The team focused on a specific proposed SRM strategy -- referred ...

Race and poverty appear to guide heart muscle DNA methylation in heart-failure patients

2021-04-07

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Race associates with the risk of death from end-stage heart failure. So, identifying the molecular determinants of that risk may help the pursuit of the novel diagnosis and prognosis of heart failure, and its therapy.

A University of Alabama at Birmingham study of end-stage heart-failure patients has found that cytosine-p-guanine, or CpG, methylation of the DNA in the heart has a bimodal distribution among the patients, and that race -- African American versus Caucasian -- was the sole variable in patient records that explained the difference. A subsequent ...

Parkinson's discovery points to possible future treatment approaches

2021-04-07

More than 20 years after the discovery of the parkin gene linked to young-onset Parkinson's disease, researchers at The Ottawa Hospital and the University of Ottawa may have finally figured out how this mysterious gene protects the brain.

Using human and mouse brain samples and engineered cells, they found that the parkin protein works in two ways. First, it acts like a powerful antioxidant that disarms potentially harmful oxidants in the brain, including dopamine radicals. Second, as the brain ages and dopamine radicals continue to build up, parkin sequesters these harmful molecules in a special storage site within vulnerable nerve cells, so they can continue to ...

Why our brains miss opportunities to improve through subtraction

2021-04-07

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va. -- If, as the saying goes, less is more, why do we humans overdo so much?

In a new paper featured on the cover of Nature, University of Virginia researchers explain why people rarely look at a situation, object or idea that needs improving -- in all kinds of contexts -- and think to remove something as a solution. Instead, we almost always add some element, whether it helps or not.

The team's findings suggest a fundamental reason that people struggle with overwhelming schedules, that institutions bog down in proliferating red tape, and, of particular ...

Predicting COVID-19 outbreaks with cell phone mobility data

2021-04-07

Mobility tracking using cell phone data showing greater movement of people is a strong predictor of increased rates of COVID-19, according to new data in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

"This study shows that mobility strongly predicts [severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2] SARS-CoV-2 growth rate up to 3 weeks in the future, and that stringent measures will continue to be necessary through spring 2021 in Canada," writes Dr. Kevin Brown, Public Health Ontario, with coauthors.

Until Canadians are widely vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, nonpharmaceutical public health interventions such as physical distancing and limiting social contact will be the main population-based means of controlling the spread of the virus.

"Mobility ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

Major heart attack study reveals ‘survival paradox’: Frail men at higher risk of death than women despite better treatment

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

Ancient mind-body practice proven to lower blood pressure in clinical trial

SwRI to create advanced Product Lifecycle Management system for the Air Force

Natural selection operates on multiple levels, comprehensive review of scientific studies shows

Developing a national research program on liquid metals for fusion

AI-powered ECG could help guide lifelong heart monitoring for patients with repaired tetralogy of fallot

Global shark bites return to average in 2025, with a smaller proportion in the United States

Millions are unaware of heart risks that don’t start in the heart

What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

A new vascularized tissueoid-on-a-chip model for liver regeneration and transplant rejection

Augmented reality menus may help restaurants attract more customers, improve brand perceptions

[Press-News.org] Crohn's disease may be caused by immune signaling failureStudy reveals how T cells in the small intestine respond to bile acids, offering localized treatment direction for a cause of chronic illness