How did 500 species of a fish form in a lake? Dramatically different body clocks

Scientists discover first nocturnal cichlid species from Africa's lake Malawi that offers clues into the evolution of sleep

2021-04-08

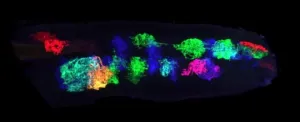

(Press-News.org) Animals are remarkably diverse in their sleep and activity patterns due to foraging strategies, social behavior and their desire to avoid predators. With more than 3,000 types of cichlids, these freshwater fish may just be one of the most diverse species in the world. Lake Malawi alone, which stretches 350 miles through eastern Africa, is home to more than 500 cichlid species. They evolved from a few species that likely entered the lake about 3 million years ago and now display very different behaviors and inhabit well-defined niches throughout the lake.

So how is it possible that so many different species can coexist in this large tropical lake? Many factors have been considered including the multitude of ecological resources available, predation, and the ability of cichlid species to evolve highly specific courtship and feeding behavior. Despite the dramatic difference between day and nightlife, the way fish exploit different times of day has not been studied systematically.

Lake Malawi's cichlids are presumed to be active during the daytime, most likely to avoid predation, although this has never been investigated scientifically. By examining alterations in the circadian timing of activity and the duration of rest-wake cycles, researchers from Florida Atlantic University in collaboration with the University of Massachusetts Amherst, are the first to identify a single nocturnal species of a Malawi cichlid - the Tropheops sp. "red cheek."

The study, published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, reveals that nocturnal behavior in the red cheek, a member of a highly speciose and ecologically diverse lineage, was maintained when fish were provided shelter, but not under constant darkness, suggesting it results from acute response to light rather than an endogenous circadian rhythm. In addition, researchers discovered that nocturnality is associated with increased eye size after correcting for evolutionary history, suggesting a link between visual processing and nighttime activity.

Lake Malawi cichlids in the study exhibited substantial and continuous variation in activity levels and patterns, and closely related species differed markedly in activity. Findings suggest that circadian regulation of activity may provide a mechanism for niche exploitation in African cichlids. Researchers also identified diversity of locomotor behavior, and together, these results provide a system for investigating the molecular and neural basis underlying variation in nocturnal activity.

To examine the effects of ecological niche and evolutionary history on the regulation of locomotor activity and rest, researchers measured locomotor activity across the circadian cycle in 11 Lake Malawi cichlid species. The species were selected for diversity in habitat, behavior and lineage representation and included the near-shore rock-dwelling clade of Malawi cichlids (mbuna) as well as representative species from another major lineage within the lake. Prior to this study, the circadian regulation of activity and rest within a lineage that inhabits a shared environment was unknown.

"Given that Malawi cichlids exhibit an impressive magnitude of diversity in an array of anatomical and behavioral traits, we predicted that they may also exhibit high magnitudes and continuous variation in rest-activity patterns. We think these differences also extend to sleep and foraging behavior, providing a system to investigate how complex traits that are critical for survival evolve," said Alex Keene, Ph.D., lead author and a professor of biological sciences in FAU's Charles E. Schmidt College of Science, on the John D. MacArthur Campus at Jupiter. "Our finding that the timing and duration of rest and activity varies dramatically, and continuously, between populations of Lake Malawi cichlids raise the possibility that these differences play a critical role in the rapid speciation of this system."

INFORMATION:

Study co-authors are Evan Lloyd, an FAU graduate student in the Department of Biological Sciences, FAU's Charles E. Schmidt College of Science; Brian Chhouk, a student at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst; and Craig Albertson, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Biology, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

This work was supported by the University of Massachusetts and the National Institutes of Health (R01GM127872 awarded to Keene).

About Florida Atlantic University:

Florida Atlantic University, established in 1961, officially opened its doors in 1964 as the fifth public university in Florida. Today, the University serves more than 30,000 undergraduate and graduate students across six campuses located along the southeast Florida coast. In recent years, the University has doubled its research expenditures and outpaced its peers in student achievement rates. Through the coexistence of access and excellence, FAU embodies an innovative model where traditional achievement gaps vanish. FAU is designated a Hispanic-serving institution, ranked as a top public university by U.S. News & World Report and a High Research Activity institution by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. For more information, visit http://www.fau.edu.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-08

Scientists are reporting results of the first frontline clinical trial to use targeted therapy to treat high-risk pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma. The study showed that the addition of brentuximab vedotin achieved excellent outcomes, reduced side effects, and allowed for reduced radiation exposures.

The study was the result of work by a multi-site consortium dedicated to pediatric Hodgkin-lymphoma. Collaborating institutions include St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Stanford University School of Medicine, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, Maine Children's Cancer Program and OSF Children's Hospital of Illinois.

A paper detailing the findings was published today in ...

2021-04-08

The Mfd protein repairs bacterial DNA, but can also, to scientists' surprise, promote mutation.

Bacterial mutations can lead to antibiotic resistance.

Understanding this second "role" of the Mfd protein opens up opportunities for combating antibiotic resistance, and also the resistance of tumours to anti-cancer drugs and therapies.

Using a specialized protein, all bacteria are capable of rapidly and effectively repairing damage to their DNA from UV. However, this mutation frequency decline (Mfd) protein plays another role and causes mutations. A team involving ...

2021-04-08

In cancer, personalised medicine takes advantage of the unique genetic changes in an individual tumour to find its vulnerabilities and fight it. Many tumours have a higher number of mutations due to a antiviral defence mechanism, the APOBEC system, which can accidentally damage DNA and cause mutations.

Researchers at IRB Barcelona led by Dr. Travis Stracker and Dr. Fran Supek have found the HMCES enzyme to be the Achilles heel of some lung tumours, specifically those with a higher number of mutations caused by the APOBEC system.

"We have discovered that blocking HMCES is very damaging to cells with an activated ...

2021-04-08

Hispanic immigrants of working age -- 20 to 54 years old -- are over 11 times more likely to die of COVID-19 than U.S.-born men and women who are not Hispanic, according to a USC study of California death certificate data from 2020.

The study, published Monday in the END ...

2021-04-08

QUT researchers have used carbon dots, created from human hair waste sourced from a Brisbane barbershop, to create a kind of "armour" to improve the performance of cutting-edge solar technology.

In a study published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry A, the researchers led by Professor Hongxia Wang in collaboration with Associate Professor Prashant Sonar of QUT's Centre for Materials Science showed the carbon nanodots could be used to improve the performance of perovskites solar cells.

Perovskites solar cells, a relatively new photovoltaic technology, are seen as the best PV candidate to deliver low-cost, highly efficient solar electricity in coming years. ...

2021-04-08

EUGENE, Ore. -- April 8, 2021 -- Researchers exploring the developing central nervous system of fruit flies have identified nonelectrical cells that transition the brain from highly plastic into a less moldable, mature state.

The cells, known as astrocytes for their star-like shapes, and associated genes eventually could become therapeutic targets, said University of Oregon postdoctoral researcher Sarah Ackerman, who led the research.

"All of the cell types and signaling pathways I looked at are present in humans," Ackerman said. "Two of the genes that I ...

2021-04-08

More than a third of the Antarctic's ice shelf area could be at risk of collapsing into the sea if global temperatures reach 4°C above pre-industrial levels, new research has shown.

The University of Reading led the most detailed ever study forecasting how vulnerable the vast floating platforms of ice surrounding Antarctica will become to dramatic collapse events caused by melting and runoff, as climate change forces temperatures to rise.

It found that 34% of the area of all Antarctic ice shelves - around half a million square kilometres - including 67% of ice shelf area on the Antarctic Peninsula, would be at risk of destabilisation under 4°C of warming. Limiting temperature ...

2021-04-08

INDIANAPOLIS--Worldwide, 1 in 4 people will suffer from a depressive episode in their lifetime.

While current diagnosis and treatment approaches are largely trial and error, a breakthrough study by Indiana University School of Medicine researchers sheds new light on the biological basis of mood disorders, and offers a promising blood test aimed at a precision medicine approach to treatment.

Led by Alexander B. Niculescu, MD, PhD, Professor of Psychiatry at IU School of Medicine, the study was published today in the high impact journal Molecular Psychiatry . The work builds on previous research conducted by Niculescu and his colleagues into blood biomarkers that track suicidality as well as pain, post-traumatic stress ...

2021-04-08

The almost 15-million-year-old Nördlinger Ries is an asteroid impact crater filled with lake sediments. Its structure is comparable to the craters currently being explored on Mars. In addition to various other deposits on the rim of the basin, the crater fill is mainly formed by stratified clay deposits. Unexpectedly, a research team led by the University of Göttingen has now discovered a volcanic ash layer in the asteroid crater. In addition, the team was able to show that the ground under the crater is sinking in the long term, which provides important ...

2021-04-08

LOUISVILLE, Ky. - When a new drug is being developed, the first question is, "Does it work?" The second question is, "Does it do harm?" No matter how effective a therapy is, if it harms the patient in the process, it has little value.

Doctoral student Robert Skolik and Associate Professor Michael Menze, Ph.D., in the Department of Biology at the University of Louisville, have found a way to make cell cultures respond more closely to normal cells, allowing drugs to be screened for toxicity earlier in the research timeline.

The vast majority of cells used for biomedical research are derived from cancer tissues stored in biorepositories. They are cheap to maintain, easy to grow and multiply quickly. Specifically, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] How did 500 species of a fish form in a lake? Dramatically different body clocks

Scientists discover first nocturnal cichlid species from Africa's lake Malawi that offers clues into the evolution of sleep