Modern human brain originated in Africa around 1.7 million years ago

2021-04-08

(Press-News.org) Modern humans are fundamentally different from our closest living relatives, the great apes: We live on the ground, walk on two legs and have much larger brains. The first populations of the genus Homo emerged in Africa about 2.5 million years ago. They already walked upright, but their brains were only about half the size of today's humans. These earliest Homo populations in Africa had primitive ape-like brains - just like their extinct ancestors, the australopithecines. So when and where did the typical human brain evolve?

CT comparisons of skulls reveal modern brain structures

An international team led by Christoph Zollikofer and Marcia Ponce de León from the Department of Anthropology at the University of Zurich (UZH) has now succeeded in answering these questions. "Our analyses suggest that modern human brain structures emerged only 1.5 to 1.7 million years ago in African Homo populations," Zollikofer says. The researchers used computed tomography to examine the skulls of Homo fossils that lived in Africa and Asia 1 to 2 million years ago. They then compared the fossil data with reference data from great apes and humans.

Apart from the size, the human brain differs from that of the great apes particularly in the location and organization of individual brain regions. "The features typical to humans are primarily those regions in the frontal lobe that are responsible for planning and executing complex patterns of thought and action, and ultimately also for language," notes first author Marcia Ponce de León. Since these areas are significantly larger in the human brain, the adjacent brain regions shifted further back.

Typical human brain spread rapidly from Africa to Asia

The first Homo populations outside Africa - in Dmanisi in what is now Georgia - had brains that were just as primitive as their African relatives. It follows, therefore, that the brains of early humans did not become particularly large or particularly modern until around 1.7 million years ago. However, these early humans were quite capable of making numerous tools, adapting to the new environmental conditions of Eurasia, developing animal food sources, and caring for group members in need of help.

During this period, the cultures in Africa became more complex and diverse, as evidenced by the discovery of various types of stone tools. The researchers think that biological and cultural evolution are probably interdependent. "It is likely that the earliest forms of human language also developed during this period," says anthropologist Ponce de León. Fossils found on Java provide evidence that the new populations were extremely successful: Shortly after their first appearance in Africa, they had already spread to Southeast Asia.

Brain imprints in fossil skulls reveal evolution of humans

Previous theories had little to support them because of the lack of reliable data. "The problem is that the brains of our ancestors were not preserved as fossils. Their brain structures can only be deduced from impressions left by the folds and furrows on the inner surfaces of fossil skulls," says study leader Zollikofer. Because these imprints vary considerably from individual to individual, until now it was not possible to clearly determine whether a particular Homo fossil had a more ape-like or a more human-like brain. Using computed tomography analyses of a range of fossil skulls, the researchers have now been able to close this gap for the first time.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-08

Researchers have developed a new algorithm capable of identifying features of male zebra finch songs that may underlie the distinction between a short phrase sung during courtship, and the same phrase sung in a non-courtship context. Sarah Woolley of McGill University in Montreal, Canada, and colleagues present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS Computational Biology.

Like many animals, male zebra finches adjust their vocal signals for their audience. They may sing the same sequence of syllables during courtship interactions with females as ...

2021-04-08

DALLAS - April 8, 2021 - New research has uncovered a surprising role for so-called "jumping" genes that are a source of genetic mutations responsible for a number of human diseases. In the new study from Children's Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern (CRI), scientists made the unexpected discovery that these DNA sequences, also known as transposons, can protect against certain blood cancers.

These findings, published in Nature Genetics, led scientists to identify a new biomarker that could help predict how patients will respond to cancer therapies and find new therapeutic targets for acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the deadliest type of blood cancer in adults and children.

Transposons ...

2021-04-08

Every third-grader knows that plants absorb nutrients from the soil through their roots. The fact that they also release substances into the soil is probably less well known. And this seems to make the lives of plants a lot easier.

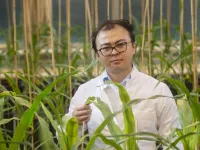

That is at least the conclusion of the current study. The participating researchers studied several maize varieties that differ significantly in their yield. In their search for the cause, they came across an enzyme, flavone synthase 2. "The high-yield inbred line 787 we studied contains large amounts of this enzyme in its roots", explains Dr. Peng Yu ...

2021-04-08

A global science collaboration using data from NASA's Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER) telescope on the International Space Station has discovered X-ray surges accompanying radio bursts from the pulsar in the Crab Nebula. The finding shows that these bursts, called giant radio pulses, release far more energy than previously suspected.

A pulsar is a type of rapidly spinning neutron star, the crushed, city-sized core of a star that exploded as a supernova. A young, isolated neutron star can spin dozens of times each second, and its whirling magnetic ...

2021-04-08

SALT LAKE CITY - A letter published today by Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI) at the University of Utah (U of U) in the New England Journal of Medicine reports that melanoma mortality among Utahns outpaced that of the rest of the United States during the period from 1975 to 2013. Melanoma death rates have been decreasing in recent years both in Utah and the United States, a trend likely attributable to new, more effective treatments, like immunotherapy. However, melanoma remains the deadliest type of skin cancer, and the incidence of melanoma diagnoses in Utahns is higher than in any other ...

2021-04-08

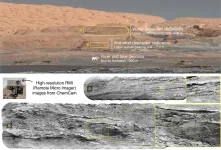

LOS ALAMOS, N.M., April 8, 2021-While attention has been focused on the Perseverance rover that landed on Mars last month, its predecessor Curiosity continues to explore the base of Mount Sharp on the red planet and is still making discoveries. Research published today in the journal Geology shows that Mars had drier and wetter eras before drying up completely about 3 billion years ago.

"A primary goal of the Curiosity mission was to study the transition between the habitable environment of the past, to the dry and cold climate that Mars has now. These rock layers recorded that change in great detail," said Roger Wiens, a coauthor on the paper and scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, ...

2021-04-08

PHILADELPHIA (April 8, 2021) - Many factors, including need, affect healthcare use. Strategies geared to enhancing the provision and access to healthcare must consider the various mechanisms that contribute to healthcare need and use. Until now, the mechanism of violence and its impact on both health and healthcare use has not been investigated.

A new study from the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing (Penn Nursing) is one of the first to examine the association between violence exposure and healthcare service utilization in Mexico. Results are published in the International Journal of Health Equity.

Widespread violence in Mexico can impact health through various channels. The study ...

2021-04-08

When it comes to choosing a partner, humans tend to be attracted by characteristics like personality and common interests. In contrast, insects tend to be a bit shallow, as they choose a mate based on appearance, and in some cases, smells. One example is the leaf beetle, which produces chemical pheromones that are on their cuticles, or the exterior surface of the beetle. They use these 'scents' to assess beetle sex and mating status (whether beetles are sexually mature or not).

Kari Segraves, professor of biology in the College of Arts and Sciences, is interested in researching the chemical and visual signals that contribute to mate selection by these beetles. This work is part of a larger project focused on understanding how new species are formed. By definition, species are related ...

2021-04-08

Ion channels play an indispensable role in cellular physiology, and understanding the physical features that affect ion channel functions is a matter of considerable interest to biologists. Given that mechanosensitivity is an intrinsic feature of cells, the complex set of mechanical stresses acting on a cell at any time represents an important consideration in the field of cellular physiology. In fact, stretching forces created by mechanical stress are sometimes necessary to activate ion channels. As Professor Masayuki Iwamoto and Professor Shigetoshi Oiki of the University of Fukui ...

2021-04-08

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Six years ago, Michael Niederweis, Ph.D., described the first toxin ever found for the deadly pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This toxin, tuberculosis necrotizing toxin, or TNT, became the founding member of a novel class of previously unrecognized toxins present in more than 600 bacterial and fungal species, as determined by protein sequence similarity. The toxin is released as M. tuberculosis bacteria survive and grow inside their human macrophage host, killing the macrophage and allowing the escape and spread of the bacteria.

For 132 years, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Modern human brain originated in Africa around 1.7 million years ago