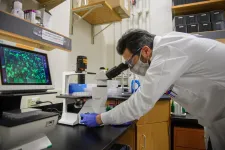

(Press-News.org) WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - New insights into the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infections could bring better treatments for COVID-19 cases.

An international team of researchers unexpectedly found that a biochemical pathway, known as the immune complement system, is triggered in lung cells by the virus, which might explain why the disease is so difficult to treat. The research is published this week in the journal Science Immunology.

The researchers propose that the pairing of antiviral drugs with drugs that inhibit this process may be more effective. Using an in vitro model using human lung cells, they found that the antiviral drug Remdesivir, in combination with the drug Ruxolitinib, inhibited this complement response.

This is despite recent evidence that trials of using Ruxolitinib alone to treat COVID-19 have not been promising.

To identify possible drug targets, Majid Kazemian, assistant professor in the departments of computer science and biochemistry at Purdue University, said the research team examined more than 1,600 previously FDA-approved drugs with known targets.

"We looked at the genes that are up-regulated by COVID-19 but down-regulated by specific drugs, and Ruxolitinib was the top drug with that property," he said.

Within the last few years, scientists have discovered that the immune complement system - a complex system of small proteins produced by the liver that aids, or complements, the body's antibodies in the fight against blood-borne pathogens - can work inside cells and not just in the bloodstream.

Surprisingly, the study found that this response is triggered in cells of the small structures in the lungs known as alveoli, Kazemian said.

"We observed that SARS-CoV2 infection of these lung cells causes expression of an activated complement system in an unprecedented way," Kazemian said. "This was completely unexpected to us because we were not thinking about activation of this system inside the cells, or at least not lung cells. We typically think of the complement source as the liver."

Claudia Kemper, senior investigator and chief of the Complement and Inflammation Research Section of the National Institutes of Health, was among the first to characterize novel roles of the complement system in the immune system. She agreed these latest findings are surprising.

"The complement system is traditionally considered a liver-derived and blood-circulating sentinel system that protects the host against infections by bacteria, fungi and viruses," she said. "It is unexpected that in the setting of a SARS-CoV2 infection, this system rather turns against the host and contributes to the detrimental tissue inflammation observed in severe COVID-19. We need to think about modulation of this intracellular, local, complement when combating COVID-19."

Dr. Ben Afzali, an Earl Stadtman Investigator of the National Institute of Health's National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, said there are now indications that this has implications for difficulties in treating COVID-19.

"These findings provide important evidence showing not only that complement-related genes are amongst the most significant pathways induced by SARS-CoV2 in infected cells, but also that activation of complement occurs inside of lung epithelial cells, i.e., locally where infection is present," he said.

"This may explain why targeting the complement system outside of cells and in the circulation has, in general, been disappointing in COVID-19. We should probably consider using inhibitors of complement gene transcription or complement protein activation that are cell permeable and act intracellularly instead."

Afzali cautions that appropriate clinical trials should be conducted to establish whether a combination treatment provides a survival benefit.

"The second finding that I think is important is that the data suggest potential benefit for patients with severe COVID-19 from combinatorial use of an antiviral agent together with an agent that broadly targets complement production or activation within infected cells," he said. "These data are promising, but it is important to acknowledge that we carried out the drug treatment experiments in cell lines infected with SARS-CoV2. So, in and of themselves they should not be used to direct treatment of patients."

Kemper added that the unexpected findings bring more questions.

"A currently unexplored and possibly therapeutically interesting aspect of our observations is also whether the virus utilizes local complement generation and activation to its benefit, for example, for the processes underlying cell infection and replication," she said.

About Purdue University

Purdue University is a top public research institution developing practical solutions to today's toughest challenges. Ranked the No. 5 Most Innovative University in the United States by U.S. News & World Report, Purdue delivers world-changing research and out-of-this-world discovery. Committed to hands-on and online, real-world learning, Purdue offers a transformative education to all. Committed to affordability and accessibility, Purdue has frozen tuition and most fees at 2012-13 levels, enabling more students than ever to graduate debt-free. See how Purdue never stops in the persistent pursuit of the next giant leap at https://purdue.edu/.

COVID-19 causes 'unexpected' cellular response in the lungs, research finds

2021-04-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

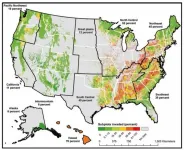

New Forest Service assessment delivers research on invasive species

2021-04-08

MADISON, WI, April 8, 2021 - USDA Forest Service scientists have delivered a new comprehensive assessment of the invasive species that confront America's forests and grasslands, from new arrivals to some that invaded so long ago that people are surprised to learn they are invasive.

The assessment, titled "Invasive Species in Forests and Rangelands of the United States: A Comprehensive Science Synthesis for the United States Forest Sector," serves as a one-stop resource for land managers who are looking for information on the invasive species that are already affecting the landscape, the species that may threaten the landscape, and what is known about control ...

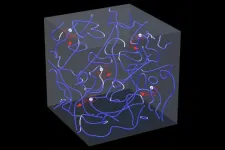

FSU engineering researchers visualize the motion of vortices in superfluid turbulence

2021-04-08

Nobel laureate in physics Richard Feynman once described turbulence as "the most important unsolved problem of classical physics."

Understanding turbulence in classical fluids like water and air is difficult partly because of the challenge in identifying the vortices swirling within those fluids. Locating vortex tubes and tracking their motion could greatly simplify the modeling of turbulence.

But that challenge is easier in quantum fluids, which exist at low enough temperatures that quantum mechanics -- which deals with physics on the scale of atoms or subatomic particles -- govern their behavior.

In a new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Florida State University researchers ...

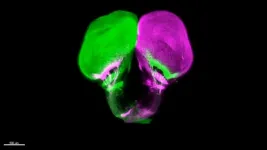

A discovery that "literally changes the textbook"

2021-04-08

The network of nerves connecting our eyes to our brains is sophisticated and researchers have now shown that it evolved much earlier than previously thought, thanks to an unexpected source: the gar fish.

Michigan State University's Ingo Braasch has helped an international research team show that this connection scheme was already present in ancient fish at least 450 million years ago. That makes it about 100 million years older than previously believed.

"It's the first time for me that one of our publications literally changes the textbook that I am teaching with," said Braasch, as assistant professor in the Department of Integrative Biology in the College ...

New pig brain maps facilitate human neuroscience discoveries

2021-04-08

URBANA, Ill. - When scientists need to understand the effects of new infant formula ingredients on brain development, it's rarely possible for them to carry out initial safety studies with human subjects. After all, few parents are willing to hand over their newborns to test unproven ingredients.

Enter the domestic pig. Its brain and gut development are strikingly similar to human infants - much more so than traditional lab animals, rats and mice. And, like infants, young pigs can be scanned using clinically available equipment, including non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI. That means researchers can test nutritional interventions in pigs, look at their effects on the developing brain via MRI, and make educated predictions about how those ...

Early humans evolved modern human-like brain organization after first African dispersal

2021-04-08

Modern human-like brains evolved comparatively late in the genus Homo and long after the earliest humans first dispersed from Africa, according to a new study. By analyzing the impressions left behind by the ancient brains that once sat inside now fossilized skulls, the authors discovered that the brains of the earliest Homo retained a primitive, great ape-like organization of the frontal lobe. The findings challenge the long-standing assumption that human-like brain organization is a hallmark of early Homo and suggest that the evolutionary history of the human brain is more complex than previously thought. Our modern brains are larger and structurally different than those of our closest living relatives, ...

Injection molding transparent glass like a plastic

2021-04-08

Researchers present a new, low-temperature method for injection-molding transparent fused silica glass, similar to how many plastic objects are manufactured. According to the authors, the process offers the possibility of producing complex and high-quality glass components using the same fabrication methods that allowed polymers to become one of the most important materials of the 21st century. The optical, thermal, mechanical and chemical properties of silicate glasses make them an ideal non-carbon based, high-performance material with applications ranging from packaging and architecture to high-throughput fiber optic ...

IntMEMOIR traces cell lineage though development and within native tissues

2021-04-08

Using a novel genetic editing system termed intMEMOIR, researchers reveal the cell lineage histories of individual cells within their native tissue context, according to a new study. The new approach provides a powerful new tool for recording cell lineage in diverse cellular systems. During multicellular development, a cell's spatial position and lineage play important roles in cell fate determination. The ability to visualize lineage relationships directly within their native tissues can provide valuable insight into the factors that affect development and disease. This promise has spurred the development of several ...

Enhanced X-Ray emissions coincide with giant radio pulses from crab pulsar

2021-04-08

X-ray emissions from the Crab Pulsar are more intense during giant radio pulses (GRPs), researchers report. The new findings provide constraints on the mechanisms underlying GRPs and may provide insights into other transient radio phenomena observed throughout the Universe. Pulsars, or rapidly spinning neutron stars, emit pulses of electromagnetic radiation from their magnetospheres and are observed from Earth as regular sequences of radio pulses. Most radio pulses from these distant objects are of a consistent intensity. Occasionally, however, sporadic and short-lived ...

Green chemistry and biofuel: the mechanism of a key photoenzyme decrypted

2021-04-08

The functioning of the enzyme FAP, useful for producing biofuels and for green chemistry, has been decrypted. This result mobilized an international team of scientists, including many French researchers from the CEA, CNRS, Inserm, École Polytechnique, the universities of Grenoble Alpes, Paris-Saclay and Aix Marseille, as well as the European Synchrotron (ESRF) and synchrotron SOLEIL. The study is published in Science on April 09, 2021.

The researchers decrypted the operating mechanisms of FAP (Fatty Acid Photodecarboxylase), which is naturally present in microscopic algae such as Chlorella. The enzyme had been identified in 2017 as able to use light energy to form hydrocarbons from fatty acids ...

Two studies support key role for immune system in shaping SARS-CoV-2 evolution

2021-04-08

Two studies published in the open-access journal PLOS Pathogens provide new evidence supporting an important role for the immune system in shaping the evolution of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. These findings--and the novel technology behind them--improve understanding of how new SARS-CoV-2 strains arise, which could help guide treatment and vaccination efforts.

For the first study, Rachel Eguia of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and colleagues sought to better understand SARS-CoV-2 by investigating a closely related virus that has circulated widely for a far longer period of time: the common-cold virus ...