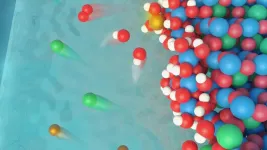

Water, or H2O, unites hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen atoms in the form of molecular hydrogen must be separated out from this compound. That process depends on a key -- but often slow -- step: the oxygen evolution reaction (OER). The OER is what frees up molecular oxygen from water, and controlling this reaction is important not only to hydrogen production but a variety of chemical processes, including ones found in batteries.

"The oxygen evolution reaction is a part of so many processes, so the applicability here is quite broad." -- Pietro Papa Lopes, Argonne assistant scientist

A study led by scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory illuminates a shape-shifting quality in perovskite oxides, a promising type of material for speeding up the OER. Perovskite oxides encompass a range of compounds that all have a similar crystalline structure. They typically contain an alkaline earth metal or lanthanides such as La and Sr in the A-site, and a transition metal such as Co in the B-site, combined with oxygen in the formula ABO3. The research lends insight that could be used to design new materials not only for making renewable fuels but also storing energy.

Perovskite oxides can bring about the OER, and they are less expensive than precious metals such as iridium or ruthenium that also do the job. But perovskite oxides are not as active (in other words, efficient at accelerating the OER) as these metals, and they tend to slowly degrade.

"Understanding how these materials can be active and stable was a big driving force for us," said Pietro Papa Lopes, an assistant scientist in Argonne's Materials Science division who led the study. "We wanted to explore the relationship between these two properties and how that connects to the properties of the perovskite itself."

Previous research has focused on the bulk properties of perovskite materials and how those relate to the OER activity. The researchers wondered, however, whether there was more to the story. After all, the surface of a material, where it reacts with its surroundings, can be completely different from the rest. Examples like this are everywhere in nature: think of a halved avocado that quickly browns where it meets the air but remains green inside. For perovskite materials, a surface that becomes different from the bulk could have important implications for how we understand their properties.

In water electrolyzer systems, which split water into hydrogen and oxygen, perovskite oxides interact with an electrolyte made of water and special salt species, creating an interface that allows the device to operate. As electrical current is applied, that interface is critical in kicking off the water-splitting process. "The material's surface is the most important aspect of how the oxygen evolution reaction will proceed: How much voltage you need, and how much oxygen and hydrogen you're going to be producing," Lopes said.

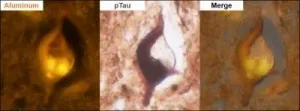

Not only is the perovskite oxide's surface different from the rest of the material, it also changes over time. "Once it's in an electrochemical system, the perovskite surface evolves and turns into a thin, amorphous film," Lopes said. "It's never really the same as the material you start with."

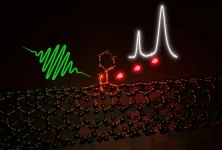

The researchers combined theoretical calculations and experiments to determine how the surface of a perovskite material evolves during the OER. To do so with precision, they studied lanthanum cobalt oxide perovskite and tuned it by "doping" the lanthanum with strontium, a more reactive metal. The more strontium was added to the initial material, the faster its surface evolved and became active for the OER -- a process the researchers were able to observe at atomic resolution with transmission electron microscopy. The researchers found that strontium dissolution and oxygen loss from the perovskite were driving the formation of this amorphous surface layer, which was further explained by computational modelling performed using the Center for Nanoscale Materials, a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

"The last missing piece to understand why the perovskites were active towards the OER was to explore the role of small amounts of iron present in the electrolyte," Lopes said. The same group of researchers recently discovered that traces of iron can improve the OER on other amorphous oxide surfaces. Once they determined that a perovskite surface evolves into an amorphous oxide, then it became clear why iron was so important.

"Computational studies help scientists understand reaction mechanisms that involve both the perovskite surface and the electrolyte," said Peter Zapol, a physicist at Argonne and study co-author. "We focused on reaction mechanisms that drive both activity and stability trends in perovskite materials. This is not typically done in computational studies, which tend to focus solely on the reaction mechanisms responsible for the activity."

The study found that the perovskite oxide's surface evolved into a cobalt-rich amorphous film just a few nanometers thick. When iron was present in the electrolyte, the iron helped accelerate the OER, while the cobalt-rich film had a stabilizing effect on the iron, keeping it active at the surface.

The results suggest new potential strategies for designing perovskite materials -- one can imagine creating a two-layer system, Lopes said, that is even more stable and capable of promoting the OER.

"The OER is a part of so many processes, so the applicability here is quite broad," Lopes said. "Understanding the dynamics of materials and their effect on the surface processes is how we can make energy conversion and storage systems better, more efficient and affordable."

INFORMATION:

The study is described in a paper published and highlighted on the Feb. 24 cover of the Journal of the American Chemical Society, "Dynamically Stable Active Sites from Surface Evolution of Perovskite Materials during the Oxygen Evolution." In addition to Lopes and Zapol, coauthors include Dong Young Chung, Hong Zheng, Pedro Farinazzo Bergamo Dias Martins, Dusan Strmcnik, Vojislav Stamenkovic, Nenad Markovic and John Mitchell at Argonne; Xue Rui and Robert Klie at the University of Illinois at Chicago; and Haiying He at Valparaiso University. This research was funded by DOE's Office of Basic Energy Sciences.

About Argonne's Center for Nanoscale Materials

The Center for Nanoscale Materials is one of the five DOE Nanoscale Science Research Centers, premier national user facilities for interdisciplinary research at the nanoscale supported by the DOE Office of Science. Together the NSRCs comprise a suite of complementary facilities that provide researchers with state-of-the-art capabilities to fabricate, process, characterize and model nanoscale materials, and constitute the largest infrastructure investment of the National Nanotechnology Initiative. The NSRCs are located at DOE's Argonne, Brookhaven, Lawrence Berkeley, Oak Ridge, Sandia and Los Alamos National Laboratories. For more information about the DOE NSRCs, please visit https://science.osti.gov/User-Facilities/User-Facilities-at-a-Glance.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit https://energy.gov/science.