Technique allows mapping of epigenetic information in single cells at scale

2021-04-12

(Press-News.org) Histones are tiny proteins that bind to DNA and hold information that can help turn on or off individual genes. Researchers at Karolinska Institutet have developed a technique that makes it possible to examine how different versions of histones bind to the genome in tens of thousands of individual cells at the same time. The technique was applied to the mouse brain and can be used to study epigenetics at a single-cell level in other complex tissues. The study is published in the journal Nature Biotechnology.

"This technique will be an important tool for examining what makes cells different from each other at the epigenetic level," says Marek Bartosovic, post-doctoral fellow at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Karolinska Institute. "We anticipate that it will be widely implemented by the broad biomedical community in a wide variety of research fields."

Even though all cells in our bodies contain exactly the same genetic information written in DNA, they read and execute this information differently. For example, a neuron in the brain reads the DNA differently than a skin cell or a fat cell. Epigenetics play a crucial role in the interpretation of the genetic information and allows the cells to execute specialized functions.

Modification of histones is one type of epigenetic information. Histones are attached to DNA like beads on a string and decorate it as "epigenetic stickers". These stickers label which genes should be turned on or off. All together this system coordinates to ensure that thousands of genes are switched on or off at the right place and time and in the right cell.

To better understand how cells become different and specialized, it is important to know which parts of the DNA are marked by which histone "stickers" in each individual organ and in each individual cell within that organ. Until recently, it was not possible to look at histone modifications of an individual cell. To examine the histone modifications in one specific cell type, a very high number of cells and cumbersome methods of cell isolation would be required. The final epigenetic histone profile of one cell type would then be an averaged view of thousands of cells.

In this study, the researchers describe a method that introduces a new way of looking at histone modifications in unprecedented detail in a single cell and at a large scale. By coupling and further optimizing other epigenomic techniques, the researchers were able to identify gene regulatory principles for brain cells in mice based on their histone profile.

"Our method--single-cell CUT&Tag--makes it possible to examine tens of thousands of single cells at the same time, giving an unbiased view of the epigenetic information in complex tissues with unparalleled resolution," Gonçalo Castelo-Branco, associate professor at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Karolinska Institute, says. "Next, we would like to apply single-cell CUT&Tag in the human brain, both in development and in various diseases. For instance, we would like to investigate which epigenetic processes contribute to neurodegeneration during multiple sclerosis and whether we would be able to manipulate these processes in order to alleviate the disease."

INFORMATION:

The research was financed by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Swedish Research Council, the Vinnova Seal of Excellence Marie-Sklodowska Curie Actions grant, the European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, the Swedish Brain Foundation, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Society for Medical Research, the Ming Wai Lau Centre for Reparative Medicine and Karolinska Institutet.

Publication: "Single-cell CUT&Tag profiles histone modifications and transcription factors in complex tissues," Marek Bartosovic, Mukund Kabbe, Gonçalo Castelo-Branco, Nature Biotechnology, online April 12, 2021, doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-00869-9

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-12

WASHINGTON--Deep in a Jamaican cave is a treasure trove of bat poop, deposited in sequential layers by generations of bats over 4,300 years.

Analogous to records of the past found in layers of lake mud and Antarctic ice, the guano pile is roughly the height of a tall man (2 meters), largely undisturbed, and holds information about changes in climate and how the bats' food sources shifted over the millennia, according to a new study.

"We study natural archives and reconstruct natural histories, mostly from lake sediments. This is the first time scientists have interpreted past bat ...

2021-04-12

BOSTON - Exercise training may slow tumor growth and improve outcomes for females with breast cancer - especially those treated with immunotherapy drugs - by stimulating naturally occurring immune mechanisms, researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Harvard Medical School (HMS) have found.

Tumors in mouse models of human breast cancer grew more slowly in mice put through their paces in a structured aerobic exercise program than in sedentary mice, and the tumors in exercised mice exhibited an increased anti-tumor immune response.

"The most exciting finding was that exercise training brought into tumors immune cells capable of killing cancer cells known as cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8+ ...

2021-04-12

Philadelphia, April 12, 2021 - Electronic cigarette (EC) use, or vaping, has both gained incredible popularity and generated tremendous controversy, but although they may be less harmful than tobacco cigarettes (TCs), they have major potential risks that may be underestimated by health authorities, the public, and medical professionals. Two cardiovascular specialists review the latest scientific studies on the cardiovascular effects of cigarette smoking versus ECs in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology, published by Elsevier. They conclude that young non-smokers should be discouraged from vaping, flavors targeted towards adolescents should be banned, and laws and regulations ...

2021-04-12

What exactly happens when the corona virus SARS-CoV-2 infects a cell? In an article published in Nature, a team from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry paints a comprehensive picture of the viral infection process. For the first time, the interaction between the coronavirus and a cell is documented at five distinct proteomics levels during viral infection. This knowledge will help to gain a better understanding of the virus and find potential starting points for therapies.

When a virus enters a cell, viral and cellular protein molecules begin to interact. Both the replication of the virus and the reaction of ...

2021-04-12

PHILADELPHIA - Residents in majority-Black neighborhoods experience higher rates of severe pregnancy-related health problems than those living in predominantly-white areas, according to a new study of pregnancies at a Philadelphia-based health system, which was led by researchers in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. The findings, published today in Obstetrics and Gynecology, suggest that neighborhood-level public health interventions may be necessary in order to lower the rates of severe maternal morbidity -- such as a heart attack, heart failure, eclampsia, or hysterectomy -- and mortality ...

2021-04-12

April 12, 2021 - For critically ill COVID-19 patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), the risk of death remains high - but is much lower than suggested by initial studies, according to a report published today by Annals of Surgery. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

The findings support the use of ECMO as "salvage therapy" for COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or respiratory failure who do not improve with conventional mechanical ventilatory support, according to the new research by Ninh T. Nguyen, MD, Chair of the Department of Surgery, University ...

2021-04-12

New research by Yale Cancer Center shows patients with early-onset colorectal cancer, age 50 and younger, have a better survival rate than patients diagnosed with the disease later in life. The study was presented virtually today at the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) annual meeting.

"Although small, we were surprised by our findings," said En Cheng, MD, MSPH, lead author of the study from Yale Cancer Center. "Past studies have shown younger colorectal patients, those under 50, were reported to experience worse survival compared with patients diagnosed at older ages. We hope this result can be inspiring for these ...

2021-04-12

In a new study led by Yale Cancer Center, researchers have advanced a tumor-targeting and cell penetrating antibody that can deliver payloads to stimulate an immune response to help treat melanoma. The study was presented today at the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) virtual annual meeting.

"Most approaches rely on direct injection into tumors of ribonucleic acids (RNAs) or other molecules to boost the immune response, but this is not practical in the clinic, especially for patients with advanced cancer," said Peter M. Glazer, MD, PhD, Chair of the Department of Therapeutic Radiology ...

2021-04-12

New research from CU Cancer Center member Scott Cramer, PhD, and his colleagues could help in the treatment of men with certain aggressive types of prostate cancer.

Published this week in the journal Molecular Cancer Research, Cramer's study specifically looks at how the loss of two specific prostate tumor-suppressing genes -- MAP3K7 and CHD1 --increases androgen receptor signaling and makes the patient more resistant to the anti-androgen therapy that is typically administered to reduce testosterone levels in prostate cancer patients.

"Doctors don't normally stratify patients based on this subtype and say, 'We're going to have to treat these people differently,' but we think this should be considered before treating ...

2021-04-12

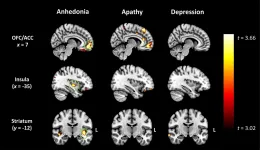

KEY POINTS:

- Loss of pleasure has been revealed as a key feature in early-onset dementia (FTD), in contrast to Alzheimer's disease.

- Scans showed grey matter deterioration in the so-called pleasure system of the brain.

- These regions were distinct from those implicated in depression or apathy - suggesting a possible treatment target.

People with early-onset dementia are often mistaken for having depression and now Australian research has discovered the cause: a profound loss of ability to experience pleasure - for example a delicious meal or beautiful sunset - related to degeneration of 'hedonic hotspots' in the brain where pleasure mechanisms are concentrated.

The University of Sydney-led ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Technique allows mapping of epigenetic information in single cells at scale