(Press-News.org) ITHACA, N.Y. - The muon is a tiny particle, but it has the giant potential to upend our understanding of the subatomic world and reveal an undiscovered type of fundamental physics.

That possibility is looking more and more likely, according to the initial results of an international collaboration - hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy's Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory - that involved key contributions by a Cornell team led by Lawrence Gibbons, professor of physics in the College of Arts and Sciences.

The collaboration, which brought together 200 scientists from 35 institutions in seven countries, set out to confirm the findings of a 1998 experiment that startled physicists by indicating that muons' magnetic field deviates significantly from the Standard Model, which is used to explain the laws that govern fundamental particles.

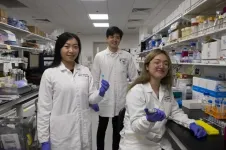

Digitizer modules undergo testing in the lab of Lawrence Gibbons, professor of physics, before being shipped to the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. Twenty-eight crates of these modules were installed around the muon g-2 ring.

"The question was, what's going on? Was the experiment wrong? Or is the theory incomplete?" Gibbons said. "And if the theory is incomplete, then confirming what's going on becomes the first terrestrial evidence of a totally new kind of fundamental particle or force that we don't know about. It would be the first experiment on Earth that is sort of the equivalent of the discovery of dark matter in space."

On April 7, the team confirmed that the original findings were correct, which means there must be more to the physics surrounding the muon than previously known.

Muons are like electrons but are more than 200 times more massive. Both are essentially tiny magnets with their own magnetic field. Muons are far more unstable, though, and decay in a few millionths of a second. They are also notoriously difficult to observe at the quantum mechanical level because the vacuum in which they exist is not a big empty cavity, but rather a bubbling, frothing, dynamic environment.

"It's your cappuccino foam version of the vacuum, where there's virtual particles winking in and out of existence all the time," Gibbons said. "And that turns out to affect the strength of the magnetic field of a muon."

To figure out why, researchers at Brookhaven National Laboratory 20 years ago set out to measure the absolute strength of muon's magnetic field. They did this by firing a beam of muons into a 14-meter-diameter magnetic ring at nearly the speed of light while a series of detectors captured data. The scientists discovered a major discrepancy in the muon's magnetic field: It was more than 3.5 standard deviations from the Standard Model predicted by theoretical physicists.

A plan was eventually hatched to repeat the Brookhaven experiment with higher precision. In 2013, the Brookhaven magnetic ring was transported to the Fermilab facility in Batavia, Illinois, where it was coupled with an even stronger particle accelerator that could produce more than 20 times the amount of muons. In 2018, the first of several experiment runs was launched.

This muon g-2 experiment - "g" refers to the value of the magnet's strength caused by its intrinsic spin, which is slightly larger than two - was successful thanks to a system of detectors developed through a joint partnership between Cornell and the University of Washington.

The University of Washington group built a set of 24 calorimeters out of lead fluoride crystals and silicon photomultipliers that measure a blue light, known as Cherenkov radiation, that results when the positrons from muon decay strike the crystals. By measuring the time and amount of light for each of about 8 billion positrons, the researchers can pinpoint the muon's precession rate, which is the frequency of its rotational wobble. The rate is directly related to the value of g-2.

The Cornell team built the digitizers that could look at the electronic signal coming out of the detectors and create a digitized version of the waveform that could be analyzed offline. The researchers were supported in the effort by the Laboratory for Elementary-Particle Physics (LEPP), and their digitizers incorporated $200,000 worth of specialized analog-to-digital converter chips donated by Texas Instruments.

Gibbons' group also built one of the pair of reconstruction packages that helped their collaborators parse and analyze the collected data, and they were assisted in getting the most precise measurements by David Rubin, the Boyce D. McDaniel Emeritus Professor of Physics (A&S), who helped correct for the spread of muon momenta in the stored beam and for the small vertical motion as the beam speeds around the magnetic ring. Two other Cornell faculty, Toichiro "Tom" Kinoshita, professor emeritus of physics, and G. Peter Lepage, the Goldwin Smith Professor of Physics, both in A&S, contributed to the Standard Model prediction of g-2, to which the project compared its results.

As a fitting final touch, Gibbons chose to make the digitizer faceplate Cornell red.

With so much subatomic information to be sifted through, six different groups worked to separately confirm the muon's precession frequency. Gibbons helped design blinding software that would ensure the groups made their calculations independently.

Then the time came to compare results.

"I have to say, it was nerve-racking. You go into the room, and there's all these points scattered all over the place from all the offsets, and you have to decide, OK, are we going to compare results now? And will they agree?" Gibbons said. "We were trying to measure something to 500 parts per billion. The range that we had was plus or minus 25 parts per million on the frequencies that we're trying to measure. There was a huge sigh of relief when we found everything agreed beautifully."

And when all the international collaborators came together online for the final unblinding of the magnetic field measurement and checked it against the original Brookhaven result?

"Oh man. It was like hats flying in the air," Gibbons said. "It was a combination of elation and relief."

The results from this first experimental run represent only 6% of the data the researchers hope to eventually collect. Additional analysis has already begun on a second and third run, which will generate three to four times as much data. It will be 10 years before all the analysis is complete.

"We landed right on top of this result that really could indicate that there's something totally new going on. We really want to push the uncertainty, the precision, to make the strongest possible statement that we can experimentally," said Gibbons, who began work on the project in 2011. "We may be onto something really profound, something we don't understand. And we still have to figure out what it is."

INFORMATION:

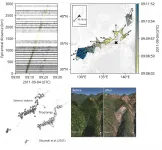

In the Cascadia subduction zone, medium and large-sized "intraslab" earthquakes, which take place at greater than crustal depths within the subducting plate, will likely produce only a few detectable aftershocks, according to a new study.

The findings could have implications for forecasting aftershock seismic hazard in the Pacific Northwest, say Joan Gomberg of the U.S. Geological Survey and Paul Bodin of the University of Washington in Seattle, in their paper published in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

Researchers now calculate aftershock forecasts in the region based in part on data from subduction zones around the world. ...

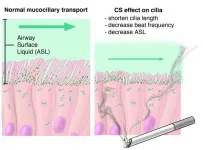

In a series of experiments that began with amoebas -- single-celled organisms that extend podlike appendages to move around -- Johns Hopkins Medicine scientists say they have identified a genetic pathway that could be activated to help sweep out mucus from the lungs of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease a widespread lung ailment.

"Physician-scientists and fundamental biologists worked together to understand a problem at the root of a major human illness, and the problem, as often happens, relates to the core biology of cells," says Doug Robinson, Ph.D., professor of cell ...

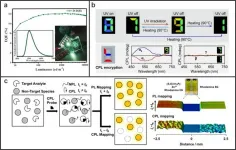

Circularly polarized light exhibits promising applications in future displays and photonic technologies. Traditionally, circularly polarized light is converted from unpolarized light by the linear polarizer and the quarter-wave plate. During this indirectly physical process, at least 50% of energy will be lost. Circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) from chiral luminophores provides an ideal approach to directly generate circularly polarized light, in which the energy loss induced by polarized filter can be reduced. Among various chiral luminophores, organic micro-/nano-structures have attracted increasing attention owing to the high quantum efficiency ...

Tsukuba, Japan - Tropical cyclones like typhoons may invoke imagery of violent winds and storm surges flooding coastal areas, but with the heavy rainfall these storms may bring, another major hazard they can cause is landslides--sometimes a whole series of landslides across an affected area over a short time. Detecting these landslides is often difficult during the hazardous weather conditions that trigger them. New methods to rapidly detect and respond to these events can help mitigate their harm, as well as better understand the physical processes themselves.

In a new study published in Geophysical Journal International, a research team led ...

Hokkaido University researchers have clarified different causes of past glacial river floods in the far north of Greenland, and what it means for the region's residents as the climate changes.

The river flowing from the Qaanaaq Glacier in northwest Greenland flooded in 2015 and 2016, washing out the only road connecting the small village of Qaanaaq and its 600 residents to the local airport. What caused the floods was unclear at the time. Now, by combining physical field measurements and meteorological data into a numerical model, researchers at Japan's Hokkaido ...

The semiconductor industry and pretty much all of electronics today are dominated by silicon. In transistors, computer chips, and solar cells, silicon has been a standard component for decades. But all this may change soon, with gallium nitride (GaN) emerging as a powerful, even superior, alternative. While not very heard of, GaN semiconductors have been in the electronics market since 1990s and are often employed in power electronic devices due to their relatively larger bandgap than silicon--an aspect that makes it a better candidate for high-voltage and high-temperature applications. Moreover, current travels quicker through GaN, which ensures fewer switching losses during switching applications.

Not everything about GaN is perfect, however. While impurities are usually desirable ...

People who have recovered from COVID-19, especially those with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions, may be at risk of developing blood clots due to a lingering and overactive immune response, according to a study led by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU) scientists.

The team of researchers, led by NTU Assistant Professor Christine Cheung, investigated the possible link between COVID-19 and an increased risk of blood clot formation, shedding new light on "long-haul COVID" - the name given to the medium- and long-term health consequences of COVID-19.

The findings may help to explain why some people who have recovered from COVID-19 exhibit symptoms of blood clotting complications after their initial recovery. In some cases, they are at increased risk of heart attack, ...

Evolutionary anthropologists from the University of Vienna and colleagues now present evidence for a different explanation, published in PNAS. A larger bony pelvic canal is disadvantageous for the pelvic floor's ability to support the fetus and the inner organs and predisposes to incontinence.

The human pelvis is simultaneously subject to obstetric selection, favoring a more spacious birth canal, and an opposing selective force that favors a smaller pelvic canal. Previous work of scientists from the University of Vienna has already led to a relatively good understanding of this evolutionary "trade-off" and how it results in the high rates of obstructed labor in modern humans. ...

They are diligently stoking thousands of bonfires on the ground close to their crops, but the French winemakers are fighting a losing battle. An above-average warm spell at the end of March has been followed by days of extreme frost, destroying the vines with losses amounting to 90 percent above average. The image of the struggle may well be the most depressingly beautiful illustration of the complexities and unpredictability of global climate warming. It is also an agricultural disaster from Bordeaux to Champagne.

It is the loss of the Arctic sea-ice due to climate warming that has, somewhat paradoxically, been implicated with severe cold and snowy mid-latitude winters.

"Climate change doesn't always manifest in the most ...

Altering a mosquito's gut genes to make them spread antimalarial genes to the next generation of their species shows promise as an approach to curb malaria, suggests a preliminary study published today in eLife.

The study is the latest in a series of steps toward using CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology to make changes in mosquito genes that could reduce their ability to spread malaria. If further studies support this approach, it could provide a new way to reduce illnesses and deaths caused by malaria.

Growing mosquito resistance to pesticides, as well as malaria parasite resistance ...