Worm infections leave African women more vulnerable to STIs

2021-04-14

(Press-News.org) Intestinal worm infections can leave women in sub-Saharan Africa more vulnerable to sexually-transmitted viral infections, a new study reveals.

The rate and severity of sexually-transmitted viral infections (STI) in the region are very high, as are those of worm infections, which when caught in the intestine can change immunity in other parts of the body.

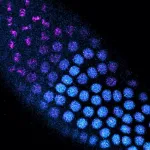

Researchers at the Universities of Birmingham and Cape Town led an international team which discovered that intestinal worm infection can change vaginal immunity and increase the likelihood of Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection - the main cause of genital herpes.

Publishing their findings today in Cell Host and Microbe, the research team also notes that worm infections significantly increase the death of tissue in the vagina (necrosis), which can result in gangrene.

However, the researchers found that they could prevent this worm-induced changes in HSV2 pathology by targeting a particular type of immune cell called eosinophils - suggesting that this pathology could be prevented or reduced by using existing drugs.

Co-author Dr. William Horsnell, from the Institute of Microbiology & Infection at the University of Birmingham and Institute of Infectious Disease and Molecular Medicine, University of Cape town commented: "Our work identifies for the first time how a worm infection can influence a very important viral STI. This is important for health workers and may help them to explain why STIs are more virulent in areas where worm infections are common.

"We show that worm infections that never colonise the vagina cause a strong change in vaginal immunity. Following a viral vaginal sexually transmitted infection the pathology caused by the virus is hugely increased. Research into STIs has, until now, largely neglected the role of worm infections in influencing the severity of these important diseases."

Rates and severity of sexually transmitted viral infections in sub-Saharan Africa are very high and are one of the world's leading causes of pathological disease. Worm infection rates are also very high in this region, but do not colonise the female reproductive tract.

"Our research shows that eosinophils can have a very important role to play in vaginal immunity - we hope that this discovery will boost efforts to understand how parasitic worm infection indirectly influence control of sexually transmitted infections," added Dr Horsnell.

The research was funded by DFG, Poliomyelitis Research Foundation, Marie Curie and National Research Foundation (South Africa). The research team is currently studying in West Africa (Togo) and South Africa how existing and past worm infections associate with risk of women having an STI.

INFORMATION:

For more information, interviews or a copy of the research paper, please contact Tony Moran, International Communications Manager, University of Birmingham on +44 (0)782 783 2312. For out-of-hours enquiries, please call +44 (0) 7789 921 165.

Notes for editors

* The University of Birmingham is ranked amongst the world's top 100 institutions. It was established by Queen Victoria in 1900 as Great Britain's first civic university, where students from all religions and backgrounds were accepted on an equal basis.

* 'Il4ra -independent vaginal eosinophil accumulation following helminth infection exacerbates epithelial ulcerative pathology following HSV-2 infection' - William Horsnell et al is published in Cell Host and Microbe.

* The research team comprised of experts from: University of Birmingham; University of Cape Town, South Africa; University of Bonn, Germany; Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway; University of Liege, Belgium; CNRS, Orleans, France; and University of Lome, Togo.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-14

Non-alcoholic fatty liver, NAFLD, is associated with several health risks. According to a new registry study led by researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden, NAFLD is linked to a 17-fold increased risk of liver cancer. The findings, published in Hepatology, underscore the need for improved follow-up of NAFLD patients with the goal of reducing the risk of cancer.

"In this study with detailed liver histology data, we were able to quantify the increased risk of cancer associated with NAFLD, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma," says first author, Tracey G. Simon, researcher at the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, and hepatologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard ...

2021-04-14

An outbreak of vomiting among dogs has been traced back to a type of animal coronavirus by researchers.

Vets across the country began reporting cases of acute onset prolific vomiting in 2019/20.

The Small Animal Veterinary Surveillance Network (SAVSNet) at the University of Liverpool asked vets for help in collecting data, with 1,258 case questionnaires from vets and owners plus 95 clinical samples from 71 animals.

Based on this data, a team from the universities of Liverpool, Lancaster, Manchester and Bristol identified the outbreak as most likely to ...

2021-04-14

ITHACA, N.Y. - Women's increased agricultural labor during harvest season, in addition to domestic house care, often comes at the cost of their health, according to new research from the Tata-Cornell Institute for Agriculture and Nutrition (TCI).

Programs aimed at improving nutritional outcomes in rural India should account for the tradeoffs that women experience when their agricultural work increases, according to the study, "Seasonal time trade-offs and nutrition outcomes for women in agriculture: Evidence from rural India," which published in the journal Food Policy on March ...

2021-04-14

PHILADELPHIA-- Humans have a uniquely high density of sweat glands embedded in their skin--10 times the density of chimpanzees and macaques. Now, researchers at Penn Medicine have discovered how this distinctive, hyper-cooling trait evolved in the human genome. In a study published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, researchers showed that the higher density of sweat glands in humans is due, to a great extent, to accumulated changes in a regulatory region of DNA--called an enhancer region--that drives the expression of a sweat gland-building gene, explaining why humans are the sweatiest ...

2021-04-14

PHOENIX, Ariz. -- April 13, 2021 -- Findings of a study by the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), an affiliate of City of Hope, suggest that increasing expression of a gene known as ABCC1 could not only reduce the deposition of a hard plaque in the brain that leads to Alzheimer's disease, but might also prevent or delay this memory-robbing disease from developing.

ABCC1, also known as MRP1, has previously been shown in laboratory models to remove a plaque-forming protein known as amyloid beta (Abeta) from specialized endothelial cells that surround and protect ...

2021-04-14

Compared to newborns conceived traditionally, newborns conceived through in vitro fertilization (IVF) are more likely to have certain chemical modifications to their DNA, according to a study by researchers at the National Institutes of Health. The changes involve DNA methylation--the binding of compounds known as methyl groups to DNA--which can alter gene activity. Only one of the modifications was seen by the time the children were 9 years old.

The study was conducted by Edwina Yeung, Ph.D., and colleagues in NIH's Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human ...

2021-04-14

A team of UBC Okanagan researchers has determined that the type of fats a mother consumes while breastfeeding can have long-term implications on her infant's gut health.

Dr. Deanna Gibson, a biochemistry researcher, along with Dr. Sanjoy Ghosh, who studies the biochemical aspects of dietary fats, teamed up with chemistry and molecular biology researcher Dr. Wesley Zandberg. The team, who conducts research in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science, explored the role of feeding dietary fat to gestating rodents to determine the generational effects of fat exposure on their offspring.

"The goal was to investigate how maternal dietary habits can impact an offspring's gut microbial communities and their associated sugar molecule patterns ...

2021-04-14

HANOVER, N.H. - April 14, 2021 - Scientists have searched for years to understand how cells measure their size. Cell size is critical. It's what regulates cell division in a growing organism. When the microscopic structures double in size, they divide. One cell turns into two. Two cells turn into four. The process repeats until an organism has enough cells. And then it stops. Or at least it is supposed to.

The complete chain of events that causes cell division to stop at the right time is what has confounded scientists. Beyond being a textbook problem, the question relates to serious medical challenges: ...

2021-04-14

LOS ANGELES (April 13, 2021) -- The Lundquist Institute (TLI) Investigator Dong W. Chang, MD, and his colleagues' study on critically ill patients and ICU treatments was published in JAMA Internal Medicine. The study - "Evaluation of Time-Limited Trials Among Critically Ill Patients with Advanced Medical Illnesses and Reduction of Nonbeneficial ICU Treatments" - found that training physicians to communicate with family members of critically ill patients using a structured approach, which promotes shared decision-making, improved the quality of family meetings. This intervention was associated with reductions in invasive ICU treatments that prolonged suffering without benefit for patients and their families.

"Invasive ICU treatments are frequently delivered to patients ...

2021-04-14

In April 2019, scientists released the first image of a black hole in galaxy M87 using the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT). However, that remarkable achievement was just the beginning of the science story to be told.

Data from 19 observatories released today promise to give unparalleled insight into this black hole and the system it powers, and to improve tests of Einstein's General Theory of Relativity.

"We knew that the first direct image of a black hole would be groundbreaking," says Kazuhiro Hada of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, a co-author of a new study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters that ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Worm infections leave African women more vulnerable to STIs