Birds take tRNA efficiency to new heights

2021-04-14

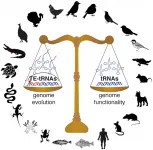

(Press-News.org) Birds have been shaped by evolution in many ways that have made them distinct from their vertebrate cousins. Over millions of years of evolution, our feathered friends have taken to the skies, accompanied by unique changes to their skeleton, musculature, respiration, and even reproductive systems. Recent genomic analyses have identified another unique aspect of the avian lineage: streamlined genomes. Although bird genomes contain roughly the same number of protein-coding genes as other vertebrates, their genomes are smaller, containing less noncoding DNA. Scientists are still exploring the potential consequences of this genome reduction on bird biology. In a new article in Genome Biology and Evolution titled "Genome size reduction and transposon activity impact tRNA gene diversity while ensuring translational stability in birds", Claudia Kutter and her colleagues reveal that, in addition to fewer protein-coding genes, bird genomes also contain surprisingly few tRNA genes, while nonetheless exhibiting the same tRNA usage patterns as other vertebrates. As tRNAs are a pivotal part of the cellular machinery that translates messenger RNA (mRNA) into protein, this suggests that birds have evolved to use their limited tRNA repertoire more efficiently.

There are many factors that go into maintaining a balanced pool of tRNAs to ensure efficient translation of proteins. While there are theoretically 64 possible anticodons--three-nucleotide sequences that base-pair with mRNA codons during translation--there are only 20 standard amino acids, meaning that there are generally tRNAs with different anticodons that bind to the same amino acid, referred to as an isoacceptor family. Moreover, the geometry of pairing between the nucleotides in the third position of the codon and anticodon allows for "wobble" base-pairing, enabling a single tRNA anticodon to bind to multiple codons. tRNA genes, even within the same isoacceptor family, can also differ in their sequences, transcription rates, and translation efficiency. Due to all of these factors, ensuring adequate levels of various tRNA molecules for efficient translation in a cell is a complex biological problem.

To investigate the different ways this problem has been solved across vertebrates, Kutter and her co-authors from the Karolinska Institute and Uppsala University in Sweden--including postdoc Jente Ottenburghs, graduate student Keyi Geng, and assistant professor at Uppsala University Alexander Suh--undertook the first comprehensive overview of tRNA diversity and evolution in vertebrates. (Ottenburghs has written about their study, including the surprising way this collaboration came about, in a post on his blog, Avian Hybrids.) Based on their findings in mammals, the authors extrapolated a uniform set of 500 tRNA genes that they expected to remain relatively consistent across lineages. However, when they added 55 avian genomes to their study, representing all of the major bird lineages, they came across some unexpected findings: "To our surprise, there was much more divergence across vertebrates than we expected to find," says Kutter. In particular, bird genomes stood out, containing an average of just 169 tRNA genes compared to 466 in reptiles, 579 in mammals, 813 in fish, and 1,229 in amphibians. According to Kutter, "While ongoing genome assembly efforts had shown that bird genomes have a smaller genome size, we were not expecting that this would also affect tRNA genes, since tRNA gene redundancy ensures that enough tRNA molecules are transcribed for efficient mRNA translation."

This led the authors to a new question: What did this contraction in tRNAs mean for translation in birds? While tRNA gene number and complexity were greatly reduced compared to other vertebrates, in general, the authors found that preferences for certain isoacceptor families were in line with the wobble pairing strategies observed in other eukaryotic genomes, suggesting that tRNA gene usage in birds follows the overall codon usage seen in vertebrates. This led the researchers to posit that the functional constraints on tRNAs seen in other vertebrates were maintained during early avian evolution: "Despite this decrease [in tRNAs] millions of years ago, the pool of tRNA anticodons and mRNA codons is still balanced across bird species to ensure optimal translational efficiencies."

Another surprising element to the study was the impact of transposable elements on the repertoire of tRNA genes in avian genomes. In some bird genomes studied, in addition to finding functional tRNA genes, Ottenburghs et al. identified hundreds, sometimes thousands, of tRNA-like sequences embedded in transposable elements. While most transposable elements are silenced by epigenetic control mechanisms and become nonfunctional, some may remain active and create new regulatory roles through their mobilization. Through multiplication of transposable elements, the embedded tRNA-like sequences may be carried to new genomic locations, where selection will constrain the tRNA gene sequence, whereas the accompanying transposable element sequence may erode. This process contributes to shaping the pool of available tRNA genes in some avian genomes, adding another layer of complexity to tRNA gene evolution in this vertebrate lineage.

The lesson here, according to Kutter, is that "we should reconsider our current assumptions of gene functionality with regards to redundancy." To explore this idea further, Kutter plans to expand this work to include better mechanistic insight and more functional genomic studies. "It would be insightful to include more species and look deeper into branches, as well as investigate snake genomes and the early vertebrate radiation. Performing studies that go beyond current model organisms may reveal even more unexpected findings." One limitation of these potential studies is that they will require access to high-quality genome assemblies and resources, such as tissue samples from different developmental time points and suitable reagents like antibodies that work across species. Kutter believes these efforts will pay off in the long run however: "Our work has shown us yet again that evolution still has a lot of surprises up its sleeves, and we can get a glimpse into these by looking beyond model organisms."

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-14

UPTON, NY--Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) have developed a new mathematical model for predicting how COVID-19 spreads. This model not only accounts for individuals' varying biological susceptibility to infection but also their levels of social activity, which naturally change over time. Using their model, the team showed that a temporary state of collective immunity--what they coined "transient collective immunity"--emerged during early, fast-paced stages of the epidemic. However, subsequent "waves," ...

2021-04-14

An alloy is typically a metal that has a few per cent of at least one other element added. Some aluminium alloys have a seemingly strange property.

"We've known that aluminium alloys can become stronger by being stored at room temperature - that's not new information," says Adrian Lervik, a physicist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

The German metallurgist Alfred Wilm discovered this property way back in 1906. But why does it happen? So far the phenomenon has been poorly understood, but now Lervik and his colleagues from NTNU and SINTEF, the largest independent research institute in Scandinavia, have tackled that question.

Lervik recently completed his doctorate at NTNU's Department of Physics. His work explains an important part of this ...

2021-04-14

Patients who have preexisting respiratory conditions such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and live in areas with high levels of air pollution have a greater chance of hospitalization if they contract COVID-19, says a University of Cincinnati researcher.

Angelico Mendy, MD, PhD, assistant professor of environmental and public health sciences, at the UC College of Medicine, looked at the health outcomes and backgrounds of 1,128 COVID-19 patients at UC Health, the UC-affiliated health care system in Greater Cincinnati.

Mendy led a team of researchers in an individual-level study which used a statistical model to evaluate the association between long-term exposure to particulate matter less or equal to 2.5 micrometers -- it refers to a mixture of tiny particles and ...

2021-04-14

Researchers have found a long-sought enzyme that prevents cancer by enabling the breakdown of proteins that drive cell growth, and that causes cancer when disabled.

Publishing online in Nature on April 14, the new study revolves around the ability of each human cell to divide in two, with this process repeating itself until a single cell (the fertilized egg) becomes a body with trillions of cells. For each division, a cell must follow certain steps, most of which are promoted by proteins called cyclins.

Led by researchers at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, the work revealed that an enzyme called AMBRA1 labels a key class of cyclins for destruction by cellular machines that break down proteins. The work finds that the enzyme's control of cyclins is essential ...

2021-04-14

ITHACA, N.Y. - Eurasian Blackcaps are spunky and widespread warblers that breed across much of Europe. Many of them migrate south to the Mediterranean region and Africa after the breeding season. But thanks to a changing climate and an abundance of food resources offered by people across the United Kingdom and Ireland, some populations of Blackcaps have recently been heading north for the winter, spending the colder months in backyard gardens of the British Isles.

New research published this week in Global Change Biology shows some of the ways that bird feeders, fruit-bearing plants, and a warming world are changing both the movements and the physiology of the Blackcaps that spend the winter in Great Britain and Ireland.

"Many migratory birds are ...

2021-04-14

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Most young women already know that tanning is dangerous and sunbathe anyway, so a campaign informing them of the risk should take into account their potential resistance to the message, according to a new study.

Word choice and targeting a specific audience are part of messaging strategy, but there is also psychology at play, researchers say - especially when the message is telling people something they don't really want to hear.

"A lot of thought goes into the content, but possibly less thought goes into the style," said Hillary Shulman, senior author of the study and an assistant ...

2021-04-14

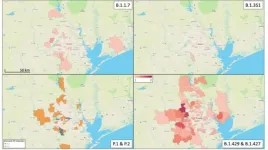

Philadelphia, April 14, 2021 - In late 2020, several concerning SARS-CoV-2 variants emerged globally. They are believed to be more easily transmissible, and there is concern that some may reduce the effectiveness of antibody treatments and vaccines. An extensive genome sequencing program run by the Houston Methodist health system has identified all six of the currently identified SARS-CoV-2 variants in their patients. A new study appearing in The American Journal of Pathology, published by Elsevier, finds that the variants are widely spread across the Houston metropolitan area.

"Before the SARS-CoV-2 virus arrived in Houston, we planned an integrated strategy to confront ...

2021-04-14

A new study by former University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign graduate student Jeffrey Kwang, now at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst; Abigail Langston, of Kansas State University; and Illinois civil and environmental engineering professor Gary Parker takes a closer look at the vertical and lateral – or depth and width – components of river erosion and drainage patterns. The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“A tree’s dendritic structure exists to provide fresh ends for leaves to grow and collect as much light as possible,” Parker said. “If you chop off some branches, they will regrow in a dendritic pattern. ...

2021-04-14

LA JOLLA, CALIF. - April 14, 2021 - Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute have shown that two existing drug candidates--JAK inhibitors and Mepron--hold potential as treatments for a deadly acute myeloid leukemia (AML) subtype that is more common in children. The foundational study, published in the journal Blood, is a first step toward finding effective treatments for the hard-to-treat blood cancer.

"While highly successful therapies have been found for other blood cancers, most children diagnosed with this AML subtype are still treated with harsh, toxic chemotherapies," says Ani Deshpande, Ph.D., assistant professor in Sanford Burnham Prebys' ...

2021-04-14

Half a century had passed, but UC Santa Barbara Professor Armand Kuris was sure he'd been here before. In fact, he was completely certain. After all, he had detailed notes of the location, written carefully in India ink when he was still a graduate student.

This time, though, Kuris served as a seasoned mentor for several young researchers who hadn't even been born when he first visited the site. Truth be told, many of their parents hadn't yet been born.

This was just one of many shorelines along the coast of the Pacific Northwest where the group was repeating ecological field work Kuris conducted in 1969 and 70. He teamed up with Assistant Professor Chelsea Wood of the University of Washington and her lab -- all parasite ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Birds take tRNA efficiency to new heights