Japanese-European research team discovers novel genetic mitochondrial disorder

Team of Japanese and European scientists identify a novel genetic mitochondrial disorder by analyzing DNA samples from three distinct families

2021-04-15

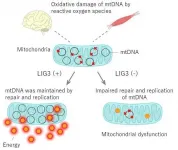

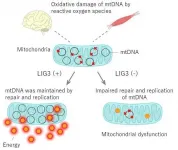

(Press-News.org) DNA ligase proteins, which facilitate the formation of bonds between separate strands of DNA, play critical roles in the replication and maintenance of DNA. The human genome encodes three different DNA ligase proteins, but only one of those proteins--DNA ligase III (LIG3)--is expressed in mitochondria. LIG3 is therefore crucial for mitochondrial health, and inactivation of the homologous protein in mice causes profound mitochondrial dysfunction and early embryonic mortality. In an article recently published in the peer-reviewed journal Brain, a team of European and Japanese scientists, led by Dr. Mariko Taniguchi-Ikeda from Fujita Health University Hospital, describes a set of seven patients with a novel mitochondrial disorder caused by biallelic variants in the gene that encodes the LIG3 protein, called the "LIG3" gene. Their report provides a description of the patients' symptoms and a mechanistic exploration of the mutations' effects.

For Dr. Taniguchi-Ikeda, the investigation began with her desire to help a young patient. "I wanted to make a distinct clinical and genetic diagnosis for the affected patient," she explains, "because his elder brother had passed away and the surviving boy was referred to my outpatient ward for detailed genetic tests." By performing whole-exome sequencing of DNA from the surviving patient, Dr. Taniguchi-Ikeda discovered that he had inherited a p.P609L LIG3 variant from his father and a p.R811Ter LIG3 variant from his mother. The parents had kept the deceased brother's dried umbilical cord, and by analyzing DNA extracted from that source, Dr. Taniguchi-Ikeda confirmed that the brother had carried the same LIG3 variants.

Having detected a novel genetic mitochondrial disorder, Dr. Taniguchi-Ikeda wished to conduct further research by identifying other patients with pathogenic LIG3 variants. She could find no other such cases in Japan, but through a collaboration with Dr. Makiko Tsutsumi from Fujita Health University and researchers in Europe, including Professor Elena Bonora from the University of Bologna and Professor Roberto De Giorgio from the University of Ferrara, she learned of two European families also affected by such variants. One was an Italian family in which three brothers had all inherited a p.K537N variant from their father and a p.G964R variant from their mother, and the other was a Dutch family in which two daughters had inherited a p.R267Ter variant from their father and a p.C999Y variant from their mother.

These patients experienced a complex syndrome involving severe gut dysmotility and neurologic abnormalities as the most consistently observed clinical signs. The neurologic abnormalities included leukoencephalopathy, epilepsy, migraine, stroke-like episodes, and neurogenic bladder. The prominent changes in the gut were decreased myenteric neuron counts and elevated fibrosis and elastin levels. Muscle pathology assessments revealed decreased staining intensities for cytochrome C oxidase.

To better characterize how the patients' LIG3 mutations could lead to such phenotypes, the researchers conducted experiments both in vitro and on zebrafish. The in vitro experiments with patient-derived fibroblasts showed that the mutations resulted in reduced LIG3 protein levels and diminished ligase activity. The consequent deficits in mitochondrial DNA maintenance would do much to explain the patients' presentations. Experiments with zebrafish showed that disrupting the lig3 gene produced brain alterations and gut transit impairments analogous to those observed in the patients.

The study brings to light a novel disorder resulting from disruption of a gene that plays a critical role in the maintenance of mitochondrial DNA. In describing the importance of these findings, Dr. Taniguchi-Ikeda concludes, "Our study may facilitate efforts to diagnose patients with mitochondrial diseases. Our findings will also be beneficial to future investigations into the mitochondrial DNA repair system."

INFORMATION:

About Fujita Health University

Fujita Health University is a private university situated in Toyoake, Aichi, Japan. It was founded in 1964 and houses one of the largest teaching university hospitals in Japan in terms of the number of beds. With over 900 faculty members, the university is committed to providing various academic opportunities to students internationally. Fujita Health University has been ranked eighth among all universities and second among all private universities in Japan in the 2020 Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings. THE University Impact Rankings 2019 visualized university initiatives for sustainable development goals (SDGs). For the "good health and well-being" SDG, Fujita Health University was ranked second among all universities and number one among private universities in Japan. The university will also be the first Japanese university to host the "THE Asia Universities Summit" in June 2021. The university's founding philosophy is "Our creativity for the people (DOKUSOU-ICHIRI)," which reflects the belief that, as with the university's alumni and alumnae, current students also unlock their future by leveraging their creativity.

Website: https://www.fujita-hu.ac.jp/en/index.html

About Dr. Mariko Taniguchi-Ikeda from Fujita Health University

Dr. Mariko Taniguchi-Ikeda, MD, PhD, is a pediatric physician and researcher who is affiliated with the Department of Clinical Genetics at Fujita Health University Hospital as an Associate Professor. She is also affiliated with the Institute for Comprehensive Medical Science at Fujita Health University and the Department of Pediatrics at the Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine. Her research interests include molecular genetics, congenital muscular dystrophy, and pediatrics.

Funding information

This study was funded by a Telethon Grant, the city of Kobe, the Dutch Cancer Foundation, the Italian Ministry of Health, and the University of Ferrara.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-15

Infection with parasitic intestinal worms (helminths) can apparently cause sexually transmitted viral in-fections to be much more severe elsewhere in the body. This is shown by a study led by the Universities of Cape Town and Bonn. According to the study, helminth-infected mice developed significantly more severe symptoms after infection with a genital herpes viruses (Herpes Simplex Virus). The researchers suspect that these results can also be transferred to humans. The results have now appeared in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

In sub-Saharan Africa, both worm infections and sexually transmitted viral diseases are extremely com-mon. These viral infections are also often particularly severe. It is possible that these findings ...

2021-04-15

LIBREVILLE, Gabon (April 15 2021) - A team of scientists led by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and working closely with experts from the Agence Nationale des Parcs Nationaux du Gabon (ANPN) compared methodologies to count African forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis), which were recently acknowledged by IUCN as a separate, Critically Endangered species from African savannah elephants. The study is part of a larger initiative in partnership with Vulcan Inc. to provide the first nationwide census in Gabon for more than 30 years. The results of the census are expected later this ...

2021-04-15

Fifty-five years ago, America's death toll from automobile crashes was sky-high. Nearly 50,000 people died every year from motor vehicle crashes, at a time when the nation's population was much smaller than today.

But with help from data generated by legions of researchers, the country's policymakers and industry made changes that brought the number killed and injured down dramatically.

Research led to changes in everything from road construction and driver's license rules, to hospital trauma care, to laws and social norms about wearing seatbelts and driving while drunk or using a cell phone.

Now, researchers at the University ...

2021-04-15

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have transformed cancer care to the point where the popular Cox proportional-hazards model provides misleading estimates of the treatment effect, according to a new study published April 15 in JAMA Oncology.

The study, "Development and Evaluation of a Method to Correct Misinterpretation of Clinical Trial Results With Long-term Survival," suggests that some of the published survival data for these immunotherapies should be re-analyzed for potential misinterpretation.

The study's senior author, Yu Shyr, PhD, the Harold L. Moses Chair ...

2021-04-15

Scientists at the University of Southampton have conducted a study that highlights the importance of studying a full range of organisms when measuring the impact of environmental change - from tiny bacteria, to mighty whales.

Researchers at the University's School of Ocean and Earth Science, working with colleagues at the universities of Bangor, Sydney and Johannesburg and the UK's National Oceanography Centre, undertook a survey of marine animals, protists (single cellular organisms) and bacteria along the coastline of South Africa.

Lead researcher and postgraduate student ...

2021-04-15

The dynamics of the neural activity of a mouse brain behave in a peculiar, unexpected way that can be theoretically modeled without any fine tuning, suggests a new paper by physicists at Emory University. Physical Review Letters published the research, which adds to the evidence that theoretical physics frameworks may aid in the understanding of large-scale brain activity.

"Our theoretical model agrees with previous experimental work on the brains of mice to a few percent accuracy -- a degree which is highly unusual for living systems," says Ilya Nemenman, Emory professor of physics and biology and senior author of the paper.

The ...

2021-04-15

Scientists at the Institute for Cooperative Upcycling of Plastics (iCOUP), an Energy Frontier Research Center led by Ames Laboratory, have discovered a chemical process that provides biodegradable, valuable chemicals, which are used as surfactants and detergents in a range of applications, from discarded plastics. The process has the potential to create more sustainable and economically favorable lifecycles for plastics.

The researchers targeted their work on the deconstruction of polyolefins, which represents more than half of all discarded plastics, and includes nearly every kind of product imaginable-- toys, food packaging, pipe systems, water ...

2021-04-15

A new review published in EPJ H by Clara Matteuzzi, Research Director at the National Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN) and former tenured professor at the University of Milan, and her colleagues, examines almost three decades of the LHCb experiment - from its conception to operation at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) - documenting its achievements and future potential.

The LCHb experiment was originally conceived to understand the symmetry between matter and antimatter and where this symmetry is broken - known as charge conjugation parity (CP) violation. Whilst this may seem like quite an obscure area of study, it addresses one of the Universe's most fundamental questions: how it came to be dominated ...

2021-04-15

As the world's energy demands grow, so too does growing concern over the environmental impact of power production. The need for a safe, clean, and reliable energy source has never been clearer. Fusion power could fulfil such a need. A review paper published in EPJ H examines the 6-decade history of neutral particle analysis (NPA), developed in Ioffe Institute, Saint Petersburg, Russia, a vital diagnostic tool used in magnetic plasma confinement devices such as tokamaks that will house the nuclear fusion process and generate the clean energy of the future.

As ...

2021-04-15

Investigators in China and the United States have injected human stem cells into primate embryos and were able to grow chimeric embryos for a significant period of time--up to 20 days. The research, despite its ethical concerns, has the potential to provide new insights into developmental biology and evolution. It also has implications for developing new models of human biology and disease. The work appears April 15 in the journal Cell.

"As we are unable to conduct certain types of experiments in humans, it is essential that we have better models to more accurately study and understand human biology and disease," says senior author Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a professor in the Gene Expression ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Japanese-European research team discovers novel genetic mitochondrial disorder

Team of Japanese and European scientists identify a novel genetic mitochondrial disorder by analyzing DNA samples from three distinct families