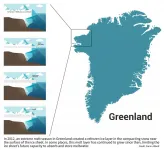

(Press-News.org) Nearly a decade ago, global news outlets reported vast ice melt in the Arctic as sapphire lakes glimmered across the previously frozen Greenland Ice Sheet, one of the most important contributors to sea-level rise. Now researchers have revealed the long-term impact of that extreme melt.

Using a new approach to ice-penetrating radar data, Stanford University scientists show that this melting left behind a contiguous layer of refrozen ice inside the snowpack, including near the middle of the ice sheet where surface melting is usually minimal. Most importantly, the formation of the melt layer changed the ice sheet's behavior by reducing its ability to store future meltwater. The research appears in Nature Communications April 20.

"When you have these extreme, one-off melt years, it's not just adding more to Greenland's contribution to sea-level rise in that year - it's also creating these persistent structural changes in the ice sheet itself," said lead study author Riley Culberg, a PhD student in electrical engineering. "This continental-scale picture helps us understand what kind of melt and snow conditions allowed this layer to form."

The 2012 melt season was caused by unusually warm temperatures exacerbated by high atmospheric pressure over Greenland - an extreme event that may have been caused or intensified by climate change. The Greenland Ice Sheet has experienced five record-breaking melt seasons since 2000, with the most recent occurring in 2019.

"Normally we'd say the ice sheet would just shrug off weather - ice sheets tend to be big, calm, slow things," said senior author Dustin Schroeder, an assistant professor of geophysics at Stanford's School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth). "This is really one of the first cases where you can say, shockingly, in some ways, these slow, calm ice sheets care a lot about a single extreme event in a particularly warm year."

Shifting scenarios

Airborne radar data, a major expansion to single-site field observations on the icy poles, is typically used to study the bottom of the ice sheet. But by pushing past technical and computational limitations through advanced modeling, the team was able to reanalyze radar data collected by flights from NASA's Operation IceBridge from 2012 to 2017 to interpret melt near the surface of the ice sheet, at a depth up to about 50 feet.

"Once those challenges were overcome, all of a sudden, we started seeing meltwater ice layers near the surface of the ice sheet," Schroeder said. "It turns out we've been building records that, as a community, we didn't fully realize we were making."

Melting ice sheets and glaciers are the biggest contributors to sea-level rise - and the most complex elements to incorporate into climate model projections. Ice sheet regions that haven't experienced extreme melt can store meltwater in the upper 150 feet, thereby preventing it from flowing into the ocean. A melt layer like the one from 2012 can reduce the storage capacity to about 15 feet in some parts of the Greenland Ice Sheet, according to the research.

The type of melt followed by rapid freeze experienced in 2012 can be compared to wintry conditions in much of the world: snow falls to the ground, a few warm days melt it a little, then when it freezes again, it creates slick ice - the kind that no one would want to drive on.

"The melt event in 2012 is impacting the way the ice sheet responds to surface melt even now," Culberg said. "These structural changes mean the way the ice sheet responds to surface melting is going to be impacted longer term."

In the long run, meltwater that can no longer be stored in the upper part of the ice sheet may drain down to the ice bed, creating slippery conditions that speed up the ice and send chunks into the ocean, raising sea levels more quickly.

Polar patterns

Greenland currently experiences change much more rapidly than its South Pole counterpart. But lessons from Greenland may be applied to Antarctica when the seasons shift, Schroeder said.

"I think now there's no question that when you're trying to project into the future, a warming Antarctic will have all these processes," Schroeder said. "If we don't use Greenland now to better understand this stuff, our capacity to understand how a warmer world will be is not a hopeful proposition."

INFORMATION:

Schroeder is also an assistant professor, by courtesy, of electrical engineering and a center fellow, by courtesy, at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. Winnie Chu of the Georgia Institute of Technology is a co-author on the paper.

The research was supported by a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship and the National Science Foundation (NSF).

PHILADELPHIA-- Researchers at Penn Medicine have identified more genetic mutations that strongly predispose younger, otherwise healthy women to peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM), a rare condition characterized by weakness of the heart muscle that begins sometime during the final month of pregnancy through five months after delivery. PPCM can cause severe heart failure and often leads to lifelong heart failure and even death. The study is published today in Circulation.

PPCM affects women in one out of every 2,000 deliveries worldwide, with about a third of those women developing heart failure for life, and about five percent of them ...

A myriad of genetic factors can influence the onset of diseases like high blood pressure, heart diseases, and type 2 diabetes. If we were to know how the DNA influences the risk of developing such diseases, we, we could shift from reactive to more preventive care, not only improving patients' quality of living but also saving money in the health system. However, tracing the connections between the DNA and disease onset requires solid statistical models that reliably work on very large datasets of several hundred thousand patients.

Matthew Robinson, Assistant Professor at the Institute ...

Our guts may not provide long-lasting systemic immunity from COVID-19, which is where immune cells circulate through the body to provide protection to other organs, finds a new study published in Frontiers in Immunology. An analysis of blood samples from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 revealed that immune cells circulating in the blood, which were triggered by the gut's response to infection, were limited in number when compared to immune cells that had been triggered elsewhere in the body.

"Although the gut is considered an important portal of entry for the virus, the immune response in the blood of COVID-19 patients is dominated by ...

Philadelphia, April 20, 2021 - American artisan cheese has become increasingly popular over the past few decades. Understanding spoilage concerns and the financial consequences of defects can improve quality, profitability, and sustainability in the American artisan cheesemaking industry. In an article appearing in the END ...

Some Himalayan glaciers are more resilient to global warming than previously predicted, new research suggests.

Rock glaciers are similar to "true" ice glaciers in that they are mixtures of ice and rock that move downhill by gravity - but the enhanced insulation provided by surface rock debris means rock glaciers will melt more slowly as temperatures rise.

Rock glaciers have generally been overlooked in studies about the future of Himalayan ice.

The new study, led by Dr Darren Jones at the University of Exeter, shows rock glaciers already account for about one twenty-fifth of Himalayan ...

A new mathematical model for the interaction of bacteria in the gut could help design new probiotics and specially tailored diets to prevent diseases. The research, from Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, was recently published in the journal PNAS.

"Intestinal bacteria have an important role to play in health and the development of diseases, and our new mathematical model could be extremely helpful in these areas," says Jens Nielsen, Professor of Systems Biology at Chalmers, who led the research.

The new paper describes how the mathematical model performed when making predictions ...

Newly published research contained in the Special Issue of the Journal of Marketing features fourteen global author teams focused on the topic of Better Marketing for a Better World. Edited by Rajesh Chandy (London Business School), Gita Johar (Columbia University), Christine Moorman (Duke University), and John Roberts (University of New South Wales), this Special Issue brings together wide-ranging research to assess, illuminate, and debate whether, when, and how marketing contributes to a better world.

The Special Issue is built on the thesis that marketing has the power to improve lives, sustain livelihoods, strengthen societies, and benefit the world at large. It calls for a renewed ...

PORTLAND, Ore. - Policies designed to prevent the misuse of opioids may have the unintended side effect of limiting access to the pain-relieving drugs by terminally ill patients nearing the end of their life, new research led by the Oregon State University College of Pharmacy suggests.

A study of more than 2,500 hospital patients discharged to hospice care over a nine-year period showed a decreasing trend of opioid prescriptions as well as an increase in the prescribing of less powerful, non-opioid analgesics, meaning some of those patients might have been undertreated for their pain compared to similar patients in prior years.

The findings, published in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, are an important step toward optimizing ...

Philadelphia, April 20, 2021 - A collaborative study from the Center for Injury Research and Prevention (CIRP) and the Center for Autism Research (CAR) at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) identified clear strengths and a series of specific challenges autistic adolescents experience while learning to drive. The findings were recently published by the American Journal of Occupational Therapy.

Researchers conducted in-depth interviews with 17 specialized driving instructors who were trained as occupational therapists, driving rehabilitation specialists, or licensed driving instructors and who had completed additional training related ...

Flushing a toilet can generate large quantities of microbe-containing aerosols depending on the design, water pressure or flushing power of the toilet. A variety of pathogens are usually found in stagnant water as well as in urine, feces and vomit. When dispersed widely through aerosolization, these pathogens can cause Ebola, norovirus that results in violent food poisoning, as well as COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2.

Respiratory droplets are the most prominent source of transmission for COVID-19, however, alternative routes may exist given the discovery of small numbers of viable viruses in urine and stool samples. Public restrooms are especially cause for concern for transmitting COVID-19 because they are ...