(Press-News.org) Scientists have spotted the largest flare ever recorded from the sun's nearest neighbor, the star Proxima Centauri.

The research, which appears today in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, was led by the University of Colorado Boulder and could help to shape the hunt for life beyond Earth's solar system.

CU Boulder astrophysicist Meredith MacGregor explained that Proxima Centauri is a small but mighty star. It sits just four light-years or more than 20 trillion miles from our own sun and hosts at least two planets, one of which may look something like Earth. It's also a "red dwarf," the name for a class of stars that are unusually petite and dim.

Proxima Centauri has roughly one-eighth the mass of our own sun. But don't let that fool you.

In their new study, MacGregor and her colleagues observed Proxima Centauri for 40 hours using nine telescopes on the ground and in space. In the process, they got a surprise: Proxima Centauri ejected a flare, or a burst of radiation that begins near the surface of a star, that ranks as one of the most violent seen anywhere in the galaxy.

"The star went from normal to 14,000 times brighter when seen in ultraviolet wavelengths over the span of a few seconds," said MacGregor, an assistant professor at the Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy (CASA) and Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences (APS) at CU Boulder.

The team's findings hint at new physics that could change the way scientists think about stellar flares. They also don't bode well for any squishy organism brave enough to live near the volatile star.

"If there was life on the planet nearest to Proxima Centauri, it would have to look very different than anything on Earth," MacGregor said. "A human being on this planet would have a bad time."

Active stars

The star has long been a target for scientists hoping to find life beyond Earth's solar system. Proxima Centauri is nearby, for a start. It also hosts one planet, designated Proxima Centauri b, that resides in what researchers call the "habitable zone"--a region around a star that has the right range of temperatures for harboring liquid water on the surface of a planet.

But there's a twist, MacGregor said: Red dwarves, which rank as the most common stars in the galaxy, are also unusually lively.

"A lot of the exoplanets that we've found so far are around these types of stars," she said. "But the catch is that they're way more active than our sun. They flare much more frequently and intensely."

To see just how much Proxima Centauri flares, she and her colleagues pulled off what approaches a coup in the field of astrophysics: They pointed nine different instruments at the star for 40 hours over the course of several months in 2019. Those eyes included the Hubble Space Telescope, the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) and NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). Five of them recorded the massive flare from Proxima Centauri, capturing the event as it produced a wide spectrum of radiation.

"It's the first time we've ever had this kind of multi-wavelength coverage of a stellar flare," MacGregor said. "Usually, you're lucky if you can get two instruments."

Crispy planet

The technique delivered one of the most in-depth anatomies of a flare from any star in the galaxy.

The event in question was observed on May 1, 2019 and lasted just 7 seconds. While it didn't produce a lot of visible light, it generated a huge surge in both ultraviolet and radio, or "millimeter," radiation.

"In the past, we didn't know that stars could flare in the millimeter range, so this is the first time we have gone looking for millimeter flares," MacGregor said.

Those millimeter signals, MacGregor added, could help researchers gather more information about how stars generate flares. Currently, scientists suspect that these bursts of energy occur when magnetic fields near a star's surface twist and snap with explosive consequences.

In all, the observed flare was roughly 100 times more powerful than any similar flare seen from Earth's sun. Over time, such energy can strip away a planet's atmosphere and even expose life forms to deadly radiation.

That type of flare may not be a rare occurrence on Proxima Centauri. In addition to the big boom in May 2019, the researchers recorded many other flares during the 40 hours they spent watching the star.

"Proxima Centauri's planets are getting hit by something like this not once in a century, but at least once a day if not several times a day," MacGregor said.

The findings suggest that there may be more surprises in store from the sun's closest companion.

"There will probably be even more weird types of flares that demonstrate different types of physics that we haven't thought about before," MacGregor said.

INFORMATION:

Other coauthors on the new study include Steven Cranmer, associate professor in APS and the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at CU Boulder; Adam Kowalski, assistant professor in APS and LASP at CU Boulder, also of the National Solar Observatory; Allison Youngblood, research scientist at LASP; and Anna Estes, undergraduate research assistant in APS.

The Carnegie Institution for Science, Arizona State University, NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center, University of Maryland, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University of Sydney, CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science, Space Telescope Science Institute, Johns Hopkins University, the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, and the University of British Columbia also contributed to this research.

RESEARCH TRIANGLE PARK, N.C. -- With Army funding, scientists invented a way to make compostable plastics break down within a few weeks with just heat and water. This advance will potentially solve waste management challenges at forward operating bases and offer additional technological advances for American Soldiers.

The new process, developed by researchers at University of California, Berkeley and the University of Massachusetts Amherst, involves embedding polyester-eating enzymes in the plastic as it's made.

When exposed to heat and water, an enzyme shrugs off its polymer shroud and starts chomping the plastic polymer into its building blocks -- in the case of biodegradable plastics, which are made primarily of the polyester known as polylactic acid, or PLA, ...

Women at high risk of breast cancer face cost-associated barriers to care even when they have health insurance, a new study has found.

The findings suggest the need for more transparency in pricing of health care and policies to eliminate financial obstacles to catching cancer early.

The study led by researchers at The Ohio State University included in-depth interviews with 50 women - 30 white, 20 Black - deemed at high risk of breast cancer based on family history and other factors. It appears in the Journal of Genetic Counseling.

The researchers considered it a given that women without any insurance would face serious barriers to preventive care including genetic counseling and testing, prophylactic mastectomy and ...

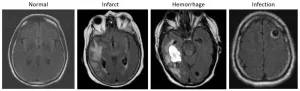

OAK BROOK, Ill. - An artificial intelligence-driven system that automatically combs through brain MRIs for abnormalities could speed care to those who need it most, according to a study published in Radiology: Artificial Intelligence.

MRI produces detailed images of the brain that help radiologists diagnose various diseases and damage from events like a stroke or head injury. Its increasing use has led to an image overload that presents an urgent need for improved radiologic workflow. Automatic identification of abnormal findings in medical images offers a potential solution, enabling improved patient care and accelerated patient discharge.

"There are an increasing number of MRIs that are performed, ...

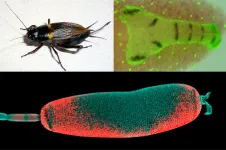

Certain signalling proteins, which are responsible for the development of innate immune function in almost all animals are also required for the formation of the dorsal-ventral (back-belly) axis in insect embryos. A new study by researchers from the University of Cologne's Institute of Zoology suggests that the relevance of these signalling proteins for insect axis formation has increased independently several times during evolution. For example, the research team found similar evolutionary patterns in the Mediterranean field cricket as in the fruit fly Drosophila, although the two insects are only very distantly related and previous observations suggested different evolutionary ...

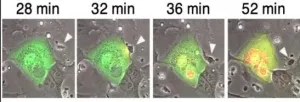

Metaplasia is defined as the replacement of a fully differentiated cell type by another. There are several classical examples of metaplasia, one of the most frequent is called Barrett's oesophagus. Barrett's oesophagus is characterized by the replacement of the keratinocytes by columnar cells in the lower oesophagus upon chronic acid reflux. This metaplasia is considered a precancerous lesion that increases by around 50 times the risk of this oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Nonetheless, the mechanisms involved in the development of metaplasia in the oesophagus are still partially unknown.

In a new study published in Cell Stem Cell, researchers led by Mr. Benjamin Beck, ...

Drawing on epidemiological field studies and the FrenchCOVID hospital cohort coordinated by Inserm, teams from the Institut Pasteur, the CNRS and the Vaccine Research Institute (VRI, Inserm/University Paris-Est Créteil) studied the antibodies induced in individuals with asymptomatic or symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. The scientists demonstrated that infection induces polyfunctional antibodies. Beyond neutralization, these antibodies can activate NK (natural killer) cells or the complement system, leading to the destruction of infected cells. Antibody levels are slightly lower in asymptomatic ...

Creativity--the "secret weapon" of Homo sapiens--constituted a major advantage over Neanderthals and played an important role in the survival of the human species. This is the finding of an international team of scientists, led by the University of Granada (UGR), which has identified for the first time a series of 267 genes linked to creativity that differentiate Homo sapiens from Neanderthals.

This important scientific finding, published today in the prestigious journal Molecular Psychiatry (Nature), suggests that it was these genetic differences linked to creativity that enabled Homo sapiens to eventually replace Neanderthals. It was creativity that gave Homo sapiens the ...

Children with weakened immune systems have not shown a higher risk of developing severe COVID-19 infection despite commonly displaying symptoms, a new study suggests.

During a 16-week period which covered the first wave of the pandemic, researchers from Southampton carried out an observational study of nearly 1500 immunocompromised children - defined as requiring annual influenza vaccinations due to underlying conditions or medication. The children, their parents or guardians completed weekly questionnaires to provide information about any symptoms they had experienced, COVID-19 test results and the impact of the pandemic on their daily life.

The results, published in BMJ Open, showed that symptoms of COVID-19 infection were common in many of the children - with ...

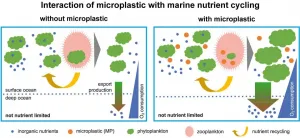

The effects of the steadily increasing amount of plastic in the ocean are complex and not yet fully understood. Scientists at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel have now shown for the first time that the uptake of microplastics by zooplankton can have significant effects on the marine ecosystem even at low concentrations. The study, published in the international journal Nature Communications, further indicates that the resulting changes may be responsible for a loss of oxygen in the ocean beyond that caused by global warming.

Plastic debris in the ocean is a widely known problem for large marine mammals, fish and seabirds. These ...

The results, exceptional first time evidence of how early flocks of domesticated sheep fed and reproduced within the Iberian Peninsula, are currently the first example of the modification of sheep's seasonal reproductive rhythms with the aim of adapting them to human needs.

The project includes technical approaches based on stable isotope analysis and dental microwear of animal remains from more than 7,500 years ago found in the Neolithic Chaves cave site in Huesca, in the central Pyrennean region of Spain. The research was coordinated from the Arqueozoology Laboratory of the UAB Department of Antiquity, with the participation of researchers from the University of Zaragoza, the Museum of Natural History of Paris, and the Catalan Institute of Human Palaeocology and Social Evolution (IPHES) ...