(Press-News.org) Animals use their sense of smell to navigate the world--to find food, sniff out mates and smell danger. But when a hungry animal smells food and a member of the opposite sex at the same time, what makes dinner the more attractive option? Exactly what is it about the odor of food that says, "Choose me?"

Research by investigators at Harvard Medical School illuminates the neurobiology that underlies food attraction and how hungry mice choose to pay attention to one object in their environment over another.

In their study, published March 3 in Nature, Stephen Liberles and co-author Nao Horio, identified the pathway that promotes attraction to food odors over other olfactory cues.

In a series of experiments, the investigators homed in on a signaling molecule called neuropeptide-Y (NPY), secreted by hunger-regulating neurons into a region of the brain known as the thalamus, which regulates a range of physiologic functions, including relaying sensory information to the cortex.

"It turns out that specific neurons 'listen' to hunger state through the release of a neurotransmitter called NPY in the thalamus," said Liberles, professor of cell biology in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS and an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Deciding between food and romance

"In mice, both food odors and sex pheromones are attractive, but are relevant for different physiological drives," said Horio, a postdoctoral researcher in the Liberles lab. "This suggests that odors activate parallel neural circuits that are shaped by physiological need."

To pinpoint the pathway that enables a mouse to make need-based decisions, Horio constructed an experiment. To start, she placed mice in an enclosure with two odor ports: one that emitted the smell of mouse chow and the other exuding pheromones from a mouse of the opposite sex. Horio noted the length of time a mouse spent lingering over each port, with longer time indicating the animal's preference.

Fed mice with full tummies found food odors and pheromones similarly attractive, but hungry mice displayed a strong preference for food odors, the scientists observed. Fed mice that had been previously exposed to a potential mate showed a distinct preference for the sex pheromones, whereas hungry mice did not. Why did hunger change the choice?

Illuminating the chemistry of food attraction

Neurons in the hypothalamus, a tiny almond-shaped gland buried deep in the brain, emit a molecule known as agouti-related peptide (AGRP). These neurons are known to trigger the drive for food. To study the effect of AGRP-secreting neurons, the researchers used a technique known as optogenetics, which allows scientists to switch neurons on and off by using light. The experiments showed that even in fed animals, AGRP neuronal activation propelled mice to investigate food odors as though they were famished.

AGRP neurons have branches that spread far and wide, so the researchers wondered which areas of the brain were being stimulated. Further experiments demonstrated that multiple AGRP neuron terminals throughout the brain were activated, but only terminals located in a region known as the paraventricular thalamus changed food odor preference. When they did, mice that were not hungry became attracted to food. Conversely, silencing AGRP projections in this area of the thalamus decreased food-odor attraction in hungry mice.

"This observation led us to believe that the persistent stimulation of AGRP neurons that occurs during fasting enhances food-odor attraction by continually signaling downstream neurons," Liberles said.

The final obstacle was to identify whether any of the three principal neurotransmitters released by AGRP neurons--AGRP, NPY, and GABA--were required for hunger-dependent odor attraction, and if so, which one.

To find out, Liberles and Horio repeated the experiments with three groups of mice--each one genetically modified to lack one of these neurotransmitters.

Hungry mice lacking AGRP and GABA remained attracted to food odor. However, hungry animals that lacked NPY were no longer more attracted to food odors than they were to pheromones. NPY knockout mice, whether their bellies were full or not, retained a lower level of attraction to food odors comparable to their attraction to pheromones. Furthermore, mice lacking a specific NPY receptor, NPY5R, also lost hunger-dependent attraction to food odor.

Moreover, after being exposed to a mate, mice lacking NPY were more attracted to pheromones than food, a finding suggesting that mechanisms other than NPY are involved in tickling the olfactory response to pheromones, Liberles said.

The state of hunger, the study suggests, initiates a complex signaling cascade that, by rendering food aromas appetizing, drives animals to seek nourishment and make food a more attractive option than other alternatives. The experiments demonstrate that the unifying signals in this cascade are NPY and its receptor NPY5R. Moving forward, future research will investigate how NPY acts on some olfactory circuits but not others and how animals learn to associate foods with certain odors.

"It seems likely that different neurotransmitters function as spotlights for other behavioral drives, with the thalamus serving as a switchboard that gives preferential attention to sensory inputs on the basis of physiological need," Liberles said.

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant to S.D.L. (R01 DC013289), a Uehara Memorial Foundation postdoctoral fellowship, funding from the Mishima Kaiun Memorial Foundation, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

STUDY SHOWS VACCINES MAY PROTECT AGAINST NEW COVID-19 STRAINS ... AND MAYBE THE COMMON COLD

A new study by Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers provides evidence that CD4+ T lymphocytes -- immune system cells also known as helper T cells -- produced by people who have received either of the two messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines for COVID-19 caused by the original SARS-CoV-2 strain also will recognize the mutant variants of the coronavirus that are rapidly becoming the dominant types worldwide.

The researchers say this suggests that T cell responses elicited or enhanced by the vaccines should be able to control the current ...

Surrey, B.C. Canada and Rochester, Minn., U.S. (April 22, 2021) - Neuroscience researchers at Mayo Clinic Orthopedics and Sports Medicine in Rochester, Minnesota, U.S., the Health and Technology District and Simon Fraser University (SFU) in Surrey, British Columbia, Canada have published the latest results of their ongoing multi-year hockey concussion study examining changes in subconcussive cognitive brain function in male youth ice hockey players.

The research team monitored brain vital signs during pre- and post-season play in 23 Bantam (age 14 or under) and Junior A (age 16 to 20) male ice-hockey players in Rochester, Minnesota.

"Brain vital signs" translates complex ...

Plastics are a part of nearly every product we use on a daily basis. The average person in the U.S. generates about 100 kg of plastic waste per year, most of which goes straight to a landfill. A team led by Corinne Scown, Brett Helms, Jay Keasling, and Kristin Persson at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) set out to change that.

Less than two years ago, Helms announced the invention of a new plastic that could tackle the waste crisis head on. Called poly(diketoenamine), or PDK, the material has all the convenient properties of traditional plastics while avoiding the environmental pitfalls, because unlike traditional plastics, PDKs can be recycled indefinitely ...

Living away from community and country, Aboriginal families of children with severe burns also face critical financial stress to cover the associated costs of health care and treatment, a new study shows.

An Australian study, led by Flinders researchers Dr Courtney Ryder and Associate Professor Tamara Mackean, found feelings of crisis were common in Aboriginal families with children suffering severe burns, with one family reporting skipping meals and others selling assets to reduce costs while in hospital.

The economic hardship was found to be worse in families who live in rural areas - some households travelling more ...

Rising levels of dementia is putting pressure on residential aged care facilities, including in rural and regional centres where nursing homes and staff are already under pressure.

Now a pilot program of personalised interventions, including residents' favourite songs, has been shown to make a big difference to dementia behaviours, drug use and carers' wellbeing.

Harmony in the Bush, a study led by Flinders University in five nursing homes in Queensland and South Australia, developed a multimodal person-centred non-pharmacological intervention program incorporating ...

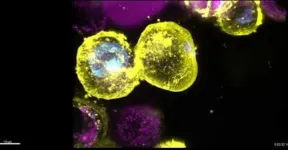

A new molecular 'freeze frame' technique has allowed WEHI researchers to see key steps in how the protein MLKL kills cells.

Small proteins called 'monobodies' were used to freeze MLKL at different stages as it moved from a dormant to an activated state, a key process that enables an inflammatory form of cell death called necroptosis. The team were able to map how the three-dimensional structure of MLKL changed, revealing potential target sites that might be targets for drugs - a potential new approach to blocking necroptosis as a treatment for inflammatory diseases.

The research, which ...

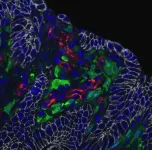

IL-11 is known to promote the development of colorectal cancer in humans and mice, but when and where IL-11 is expressed during cancer development is unknown. "To address these questions experimentally, we generated reporter mice that express the green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene in interleukin 11 (IL-11)-producing (IL11+) cells in vivo. We found IL-11+ cells in the colons of this murine colitis-associated colorectal cancer model," said Dr. Nishina, the lead author of a study published April 16 in Nature Communications. "The IL-11+ cells were absent from the colon under normal conditions but rapidly appeared in the tissues of mice with colitis and colorectal cancer."

In the study, Dr. Nishina and colleagues characterized the IL-11+ cells by flow cytometry and found that ...

The human immune defense is based on the ability of white blood cells to accurately identify disease-causing pathogens and to initiate a defense reaction against them. The immune defense is able to recall the pathogens it has encountered previously, on which, for example, the effectiveness of vaccines is based. Thus, the immune defense the most accurate patient record system that carries a history of all pathogens an individual has faced. This information however has previously been difficult to obtain from patient samples.

The learning immune system can be roughly divided into two parts, of which B cells are responsible for producing antibodies against pathogens, while T cells are responsible for destroying their targets. The measurement of antibodies by traditional laboratory ...

The study was published by the team from Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB), the Max Planck Institutes of Biochemistry and Biophysics, the Center for Synthetic Microbiology (SYNMIKRO) and the Chemistry Department at Philipps Universität Marburg, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, USA, and Université Paris-Saclay, France, online on 12 April 2021 in the journal Nature Plants.

Catalyst of life

Photosystem II (PS II) is of fundamental importance for life, as it is able to catalyse the splitting of water. The oxygen released in this reaction allows us to breathe. In addition, PS II converts light energy ...

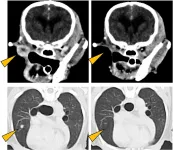

Scientists have shown that the biological molecule PD-L1 is a potential target for the treatment of metastasized oral malignant melanoma in dogs.

There are a number of cancers that affect dogs, but there are far fewer diagnosis and treatment options for these canine cancers. However, as dogs and humans are both mammals, it is likely that strategies and treatments for cancers in humans can be used for canine cancer, with minor modifications.

A team of scientists, including Associate Professor Satoru Konnai from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Hokkaido University, have demonstrated that an anti-cancer therapy that targets the cancer marker PD-L1--a target that has shown great promise for treating cancer in humans--is ...