(Press-News.org) Researchers have found that a natural molecule can effectively block the binding of a subset of human antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. The discovery may help explain why some COVID-19 patients can become severely ill despite having high levels of antibodies against the virus.

In their research, published in Science Advances today (22 April 2021), teams from the Francis Crick Institute, in collaboration with researchers at Imperial College London, Kings College London and UCL (University College London), found that biliverdin and bilirubin, natural molecules present in the body, can suppress the binding of antibodies to the coronavirus spike.

As vaccines are rolled out globally, understanding immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and also how the virus evades antibodies is critically important. However, there are still many unknowns. The ability of the immune system to control the infection and the quality of the antibody response are highly variable, and not well correlated, between individuals.

The Crick researchers were involved in the development of tests that see if a person has been exposed to the virus. The scientists discovered that the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein strongly binds to biliverdin, a molecule which was giving these proteins an unusual green colouration.

Working with teams at Imperial College London, UCL and Kings College London, they found that this natural molecule reduced antibody binding to the spike. They used blood sera and antibodies from people who were previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 and found that biliverdin could suppress the binding of human antibodies to the spike by as much as 30-50%, with some antibodies becoming ineffective at neutralising the virus.

Such a significant impact was completely unexpected, as biliverdin only binds to a very small patch on the virus' surface. To find out the mechanism at work, the team at the Crick used cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography to look in detail at the interactions between the spike, the antibodies and biliverdin. They found that biliverdin attaches to the spike N-terminal domain and stabilises it so that the spike is not able to open up and expose parts of its structure. This means that some antibodies are not able to access their target sites and so cannot bind to and neutralise the virus.

Annachiara Rosa, first author and postdoctoral training fellow in the Chromatin structure and mobile DNA Laboratory at the Crick, says: "When SARS-CoV-2 infects a patient's lungs it damages blood vessels and causes a rise in the number immune cells. Both of these effects may contribute to increasing the levels of biliverdin and bilirubin in the surrounding tissues. And with more of these molecules available, the virus has more opportunity to hide from certain antibodies. This is a really striking process, as the virus may be benefiting from a side-effect of the damage it has already caused."

Peter Cherepanov, author and a group leader of the Chromatin structure and mobile DNA Laboratory at the Crick, says: "In the first months of the pandemic, we were extremely busy churning out viral antigens for SARS-CoV-2 tests. It was a race, as these tests were urgently needed. When we finally found the time to study our green proteins, we expected a mundane answer. Instead, we were astonished to discover a new trick the virus uses to avoid antibody recognition. This is a result of a collaborative effort of several amazing teams working at the Crick and three partner universities, led purely by scientific curiosity."

The researchers will continue this work from various angles, including measuring the levels of biliverdin and other haem metabolites in patients with COVID-19 and also exploring if it is possible to hijack the binding site used by biliverdin to potentially find new ways to target the virus.

INFORMATION:

Peer reviewed

Experimental study

Cells

For further information, contact: press@crick.ac.uk or +44 (0)20 3796 5252

Notes to Editors

Reference: Rosa, A. et al. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 can recruit a haem metabolite to evade antibody immunity. Science Advances. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abg7607

Available here once published: https://advances.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abg7607

The Francis Crick Institute is a biomedical discovery institute dedicated to understanding the fundamental biology underlying health and disease. Its work is helping to understand why disease develops and to translate discoveries into new ways to prevent, diagnose and treat illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, stroke, infections, and neurodegenerative diseases.

An independent organisation, its founding partners are the Medical Research Council (MRC), Cancer Research UK, Wellcome, UCL (University College London), Imperial College London and King's College London.

The Crick was formed in 2015, and in 2016 it moved into a brand new state-of-the-art building in central London which brings together 1500 scientists and support staff working collaboratively across disciplines, making it the biggest biomedical research facility under a single roof in Europe.

http://crick.ac.uk/

Researchers have identified another potential target for neutralizing antibodies on the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein that is masked by metabolites in the blood. As a result of this masking, the target may be inaccessible to antibodies, because they must compete with metabolite molecules to bind to the otherwise open region, the study authors speculate. This competitive binding activity may represent another method of immune evasion by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Although further validation work is needed, the findings suggest that strategies to unmask this region - thus making it more visible and accessible to antibodies - may help lead to new vaccine designs. ...

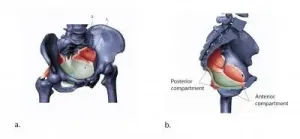

AUSTIN, Texas -- Despite advances in medicine and technology, childbirth isn't likely to get much easier on women from a biological perspective.

Engineers at The University of Texas at Austin and University of Vienna revealed in new research a series of evolutionary trade-offs that have created a near-perfect balance between supporting childbirth and keeping organs intact on a day-to-day basis. Human reproduction is unique because of the comparatively tight fit between the birth canal and baby's head, and it is likely to stay that way because of these competing biological imperatives.

The size of the pelvic floor and canal is key to keeping this balance. These opposing duties have constrained the ability of the pelvic floor to evolve over time to make childbirth easier because doing ...

Not all cancerous tumors are created equal. Some tumors, known as "hot" tumors, show signs of inflammation, which means they are infiltrated with T cells working to fight the cancer. Those tumors are easier to treat, as immunotherapy drugs can then amp up the immune response.

"Cold" tumors, on the other hand, have no T-cell infiltration, which means the immune system is not stepping in to help. With these tumors, immunotherapy is of little use.

It's the latter type of tumor that researchers Michael Knitz and radiation oncologist and University of Colorado Cancer Center member Sana Karam, MD, PhD, address in new research published this week in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. Working with mouse models in Karam's specialty area of head and neck cancers, Knitz and ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- As NASA's Perseverance rover begins its search for ancient life on the surface of Mars, a new study suggests that the Martian subsurface might be a good place to look for possible present-day life on the Red Planet.

The study, published in the journal Astrobiology, looked at the chemical composition of Martian meteorites -- rocks blasted off of the surface of Mars that eventually landed on Earth. The analysis determined that those rocks, if in consistent contact with water, would produce the chemical energy needed to support microbial communities similar to those that survive in the unlit depths of the Earth. Because these meteorites may be representative ...

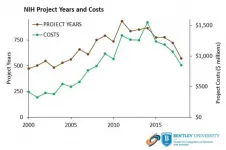

The unprecedented development of COVID-19 vaccines less than a year after discovery of this virus was enabled by more than $17 billion of research on vaccine technologies funded by the NIH prior to the pandemic, according to new research from Bentley University's Center for Integration of Science and Industry. The article, titled "NIH funding for vaccine readiness before the COVID-19 pandemic," demonstrates the critical role this broad foundation of government-funded research plays in ensuring vaccine readiness.

The report, published today in the journal Vaccine, ...

DALLAS - April 22, 2021 - Being Black or Hispanic, living in high-poverty neighborhoods, and having Medicaid or no insurance coverage are associated with higher mortality in men and women under 40 with cancer, a review by UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers found.

"Survival is not different because of biology. It's not different because of patient-level factors," says Caitlin Murphy, Ph.D., lead author of the study and an assistant professor of population and data sciences and internal medicine at UT Southwestern. "No matter which way we looked at the data, we still saw consistent and alarming differences in survival by race - and these are teens and young adults."

Other findings based on an ...

Machine learning could provide up an extra hour of warning time for debris flows along the Illgraben torrent in Switzerland, researchers report at the Seismological Society of America (SSA)'s 2021 Annual Meeting.

Debris flows are mixtures of water, sediment and rock that move rapidly down steep hills, triggered by heavy precipitation and often containing tens of thousands of cubic meters of material. Their destructive potential makes it important to have monitoring and warning systems in place to protect nearby people and infrastructure.

In her presentation at SSA, Ma?gorzata Chmiel of ETH Zürich described a machine learning approach to detecting and alerting against debris flows for the Illgraben torrent, a site in the European Alps that experiences significant debris flows and torrential ...

It seems like a smooth slab of stainless steel, but look a little closer, and you'll see a simplified cross-section of the Los Angeles sedimentary basin.

Caltech researcher Sunyoung Park and her colleagues are printing 3D models like the metal Los Angeles proxy to provide a novel platform for seismic experiments. By printing a model that replicates a basin's edge or the rise and fall of a topographic feature and directing laser light at it, Park can simulate and record how seismic waves might pass through the real Earth.

In her presentation at the Seismological Society of America (SSA)'s 2021 Annual Meeting, Park explained why these physical models can address some of the drawbacks of numerical modeling of ground motion in some cases.

Small-scale, complex structures in ...

Days after the 4 August 2020 massive explosion at the port of Beirut in Lebanon, researchers were on the ground mapping the impacts of the explosion in the port and surrounding city.

The goal was to document and preserve data on structural and façade damage before rebuilding, said University of California, Los Angeles civil and environmental engineer Jonathan Stewart, who spoke about the effort at the Seismological Society of America (SSA)'s 2021 Annual Meeting.

The effort also provided an opportunity to compare NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory satellite surveys of the blast effects with data collected from the ground surveys. Stewart and his colleagues concluded that satellite-based Damage Proxy Maps were effective at identifying severely damaged buildings and undamaged ...

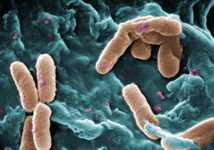

Research has identified critical factors that enable dangerous bacteria to spread disease by surviving on surfaces in hospitals and kitchens.

The study into the mechanisms which enable the opportunistic human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa to survive on surfaces, could lead to new ways of targeting harmful bacteria.

To survive outside their host, pathogenic bacteria must withstand various environmental stresses. One mechanism is the sugar molecule, trehalose, which is associated with a range of external stresses, particularly osmotic shock - sudden changes to the salt concentration surrounding cells.

Researchers ...